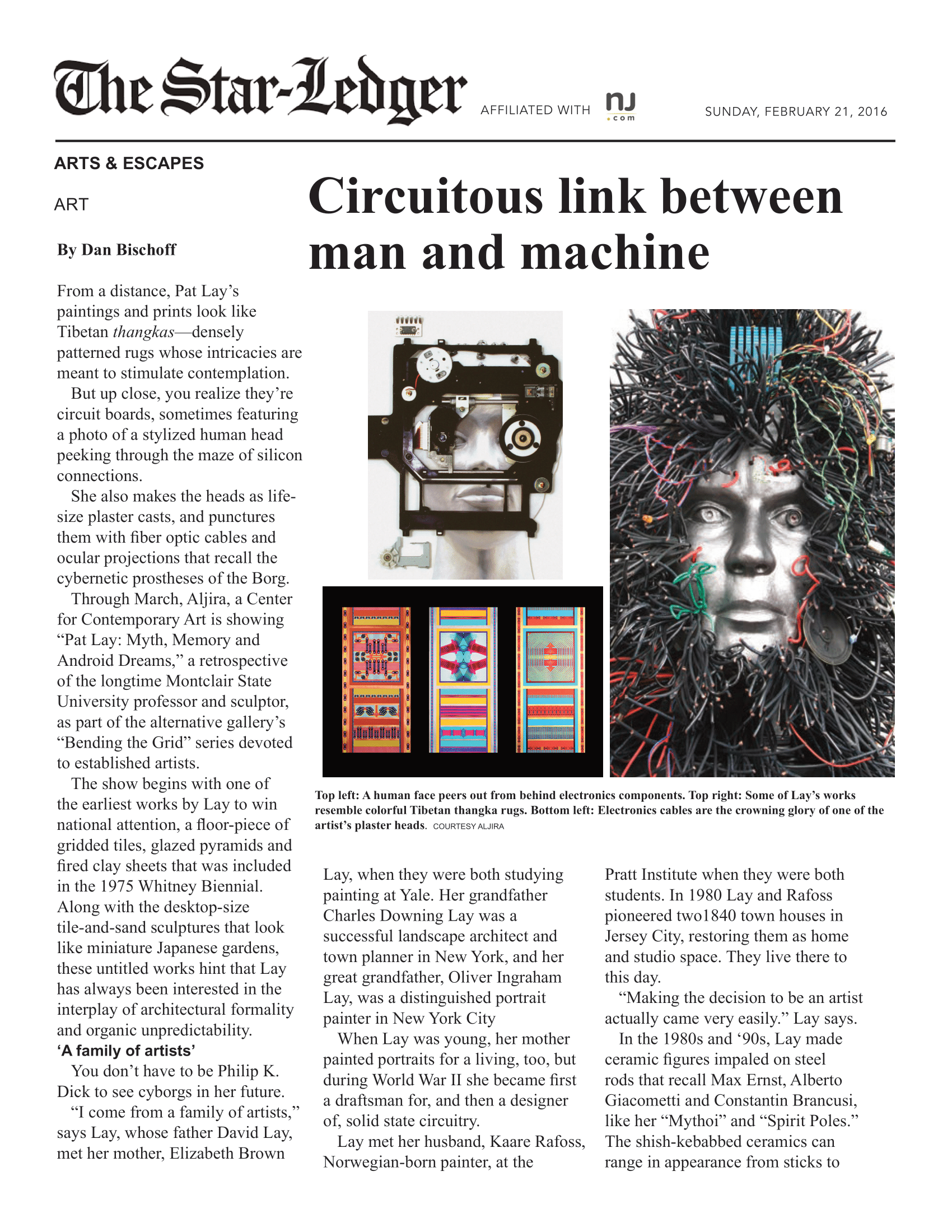

Sims, Patterson; An Interview With Patricia Lay, in catalog Myth, Memory and Android Dreams

AN INTERVIEW WITH PATRICIA LAY (2016)

By Patterson Sims, Independent Art Curator, Writer and Consultant

Originally published in Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams

Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art, Newark New Jersey

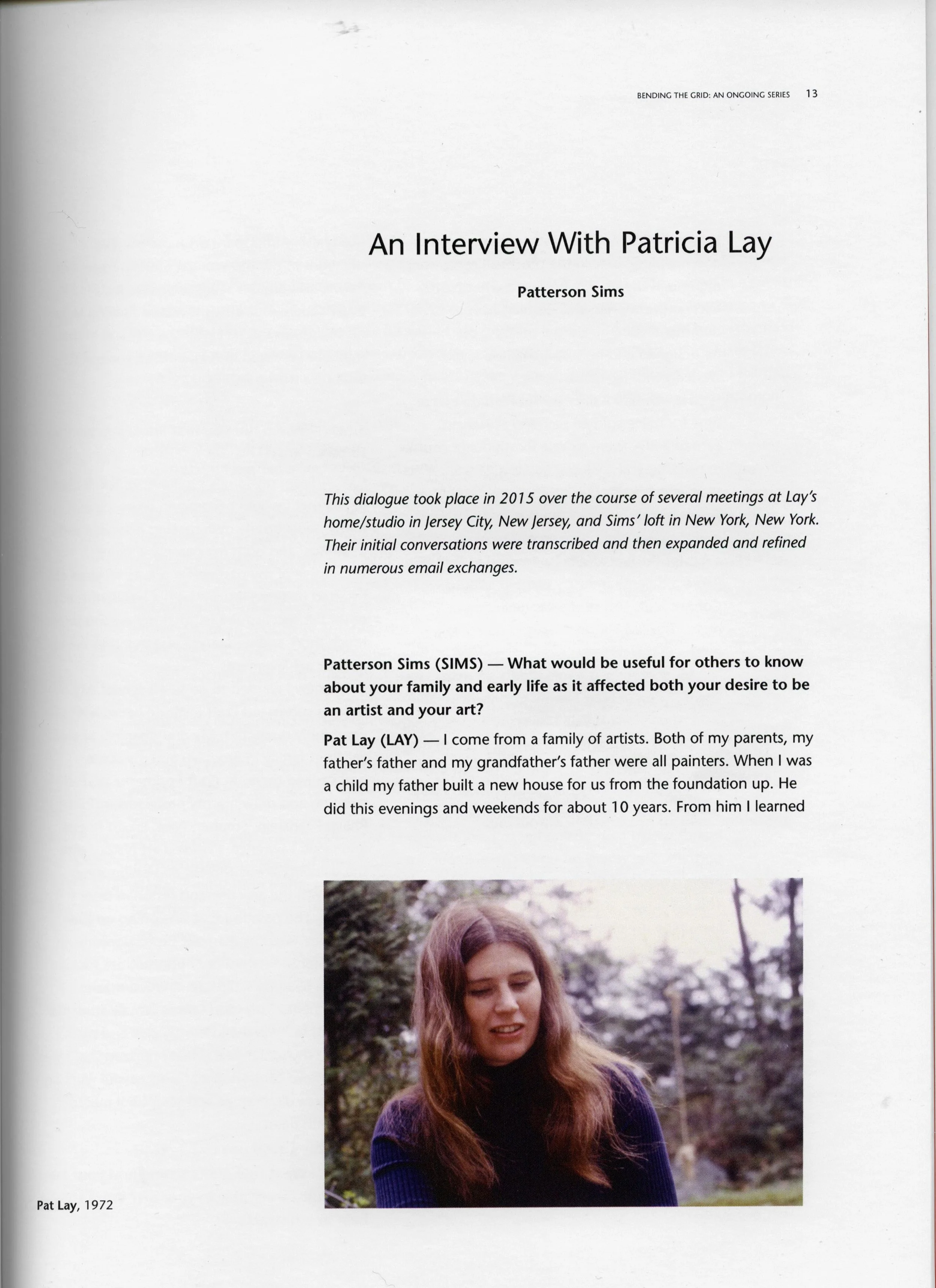

This dialogue took place in 2015 over the course of several meetings at Lay’s home/studio in Jersey City, New Jersey, and Sims’ loft in New York, New York. Their initial conversations were transcribed and then expanded and refined in numerous email exchanges.

SIMS: What would be useful for others to know about your family and early life as it impacted on your wanting to be an artist and you art?

LAY: I come from a family of artists. Both of my parents, my father’s father, and my grandfather’s father were all painters. When I was a child my father built a new house for us from the foundations up. He did this evenings and weekends for about ten years. From him I learned how to build things. He would let my brother and me participate in the process.

I remember digging in the mud, wheeling a wheelbarrow filled with concrete, and learning how to use a hammer. Before he started building our house he designed and built sailboats. He loved working with his hands. He was also a painter, but he didn’t have time for it. He studied painting at Harvard, earned a BFA, went to Yale for graduate courses in painting, and took classes at the Art Students League in NYC. Then my brother and I were born. During World War II he had the choice of going to war or working at a job for the war effort. He worked at Remington Rand, a defense industry plant in Milford, Connecticut and studied engineering at night. This led him to a life-long career as a production engineer.

My mother was a role model on many levels. She grew up in New Haven, Connecticut and studied painting at Yale University and received her BFA in 1936. After my parents married they moved to New York City and continued their study at the Art students League. When I was still very young in Connecticut my mother’s friends would commission her to paint their portraits. She would set up her easel in our living room, and they would come for sittings. This continued until I was in third grade. When I was nine my mother worked as a draftswomen for an electronics company, later she became a designer of solid-state circuits. I remember her showing me drawings with layers and layers of tracing paper with lines connecting the dots. They were plans for electronic circuitry. Recently a friend suggested that my mother ‘s rendering may have sparked my present interest in circuit boards.

The summer of 1962, between my junior and senior years at Pratt, my mother and I took a nine-week road trip to thirteen European countries. We drove from city to city visiting nearly every important art museum. The highlight of the trip was the Spoleto Festival in Italy. David Smith’s sculptures were installed in every square of the city. It was so thrilling to see his sculptures interact with the city and at this moment I realized that I identified more with sculpture than painting.

SIMS: When did you first know you wanted to be an artist?

LAY: From my family’s influences, it was clear to me that I would become an artist. I spent many hours on my own making drawings and paintings, and both my parents were very supportive of my passion for art. At ten years old I started painting lessons with a local artist, but I never felt successful. I felt that my parents were much more talented, and I was trying to live up to their achievements.

I knew I wanted to go to art school. My parents suggested Pratt Institute because it was highly respected. My grandparents knew the Pratt family in Brooklyn and my uncle had studied there. At Pratt I primarily studied painting and drawing, my professors included Phillip Pearlstein, Stephen Pace, Ernest Briggs, and Jacob Lawrence. I studied art history with the painter George McNeil and philosophy of art with the art critic and historian Dore Ashton. The painting that was going on then was dominated by Abstract Expressionism. Pratt offered very limited opportunities for women to study sculpture. It was a macho department. They didn’t allow female students to weld, so I worked in mostly clay and plaster. I was in my senior year when I realized that I was much more comfortable and successful working with three-dimensions and sculptural materials than with paint.

SIMS: What role did teaching and your later academic career play in your art? Was it help or a distraction?

LAY: Early on I realized that making art was not a secure way to make a living, and that I would have to have another profession to have a stable economic life. Teaching on the college level was the obvious choice because it’s not a nine-to-five job. As a teacher you are expected to actively pursue your specialty: art making is built into the job.

I always liked the give-and-take with students, a mutual questioning and conversation. I learned from the students and they learned from me, especially the MFA students. I started teaching at the college level when I was 27. I realized that the students saw me as a role model, and I worked hard at my career as an artist to earn their respect and trust. The academic environment also expanded my knowledge of art history, philosophy, the art world, technology and new processes.

But teaching had its distractions. It was difficult to carry through on a studio project. Many times experiments in new directions were left unresolved. The studio work would be sabotaged by an academic report that needed to be written or a grant that had to be submitted.

SIMS: How did your participation in the 1975 Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial exhibition impact your career as an artist?

LAY: Well, I guess it didn’t, really, though I thought that it would open doors. This particular biennial was large and included many emerging artists, and I was one of them. Marcia Tucker was the specific curator of the five who choose my work. The show got some decidedly negative press, but that is pretty typical for a Whitney Biennial.

SIMS: Did you have a gallery going into the exhibition?

LAY: No, and I did not have a gallery as a result of the show. It may have led to other shows, but it was not instrumental in establishing gallery representation. I was ill prepared to deal with the business of art. It was not something that was discussed at Pratt or graduate school. We were all purists and idealistic and felt that it was the gallery’s responsibility to promote our work.

SIMS: Though the grid, immaculate execution, and formalist abstraction prevail in your art, your work has gone through several phases. How might you highlight its overriding characteristics and issues?

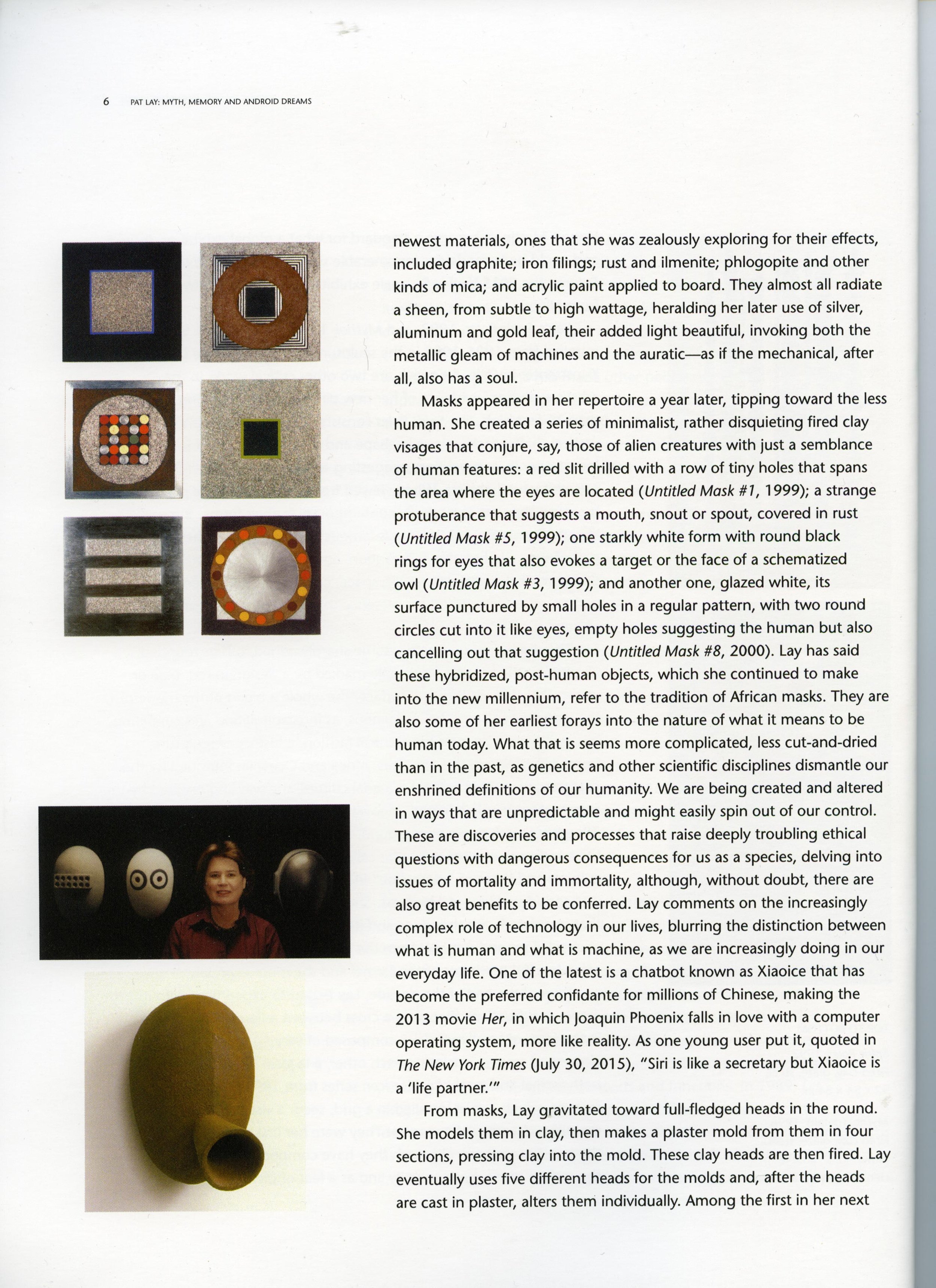

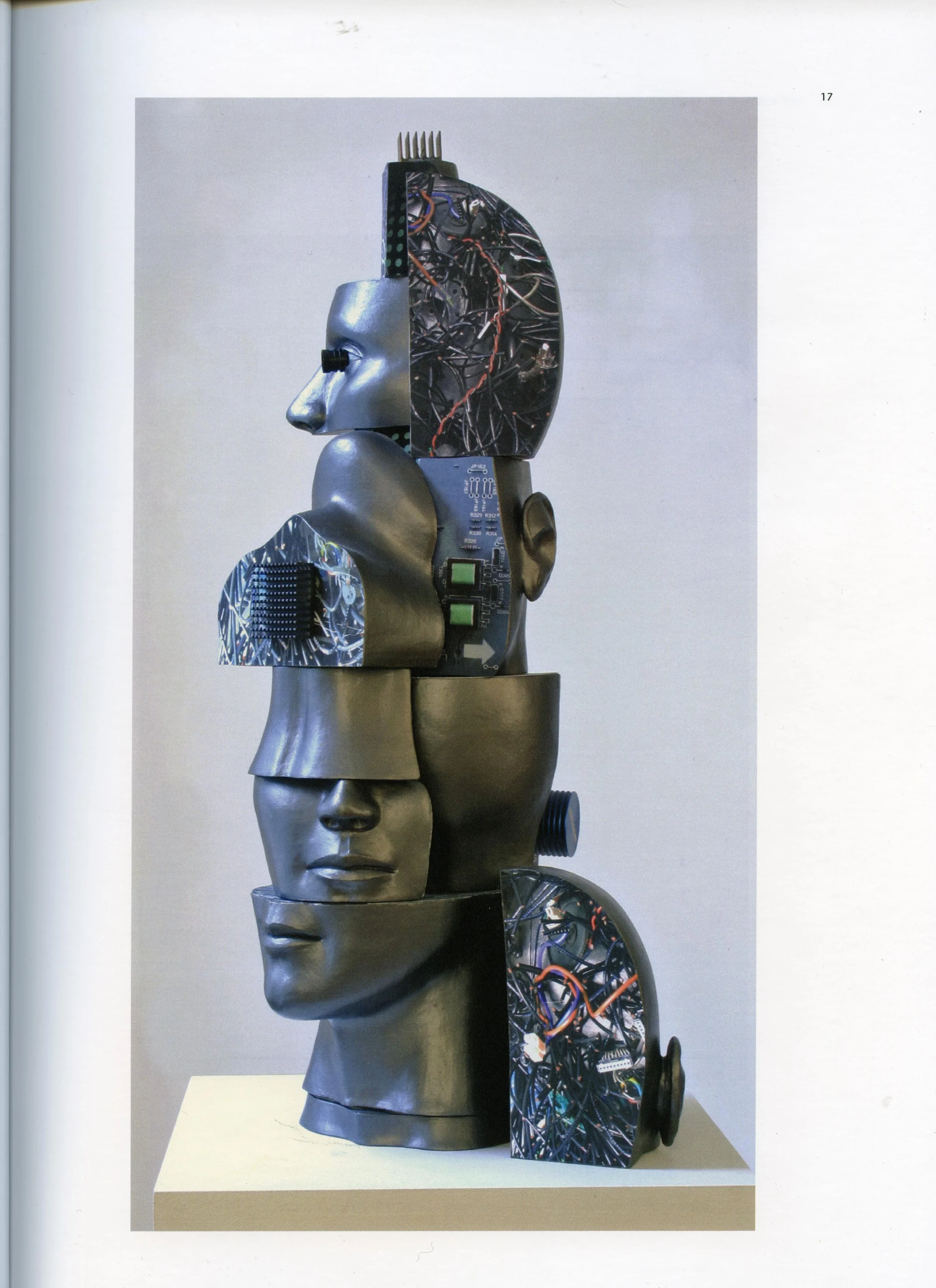

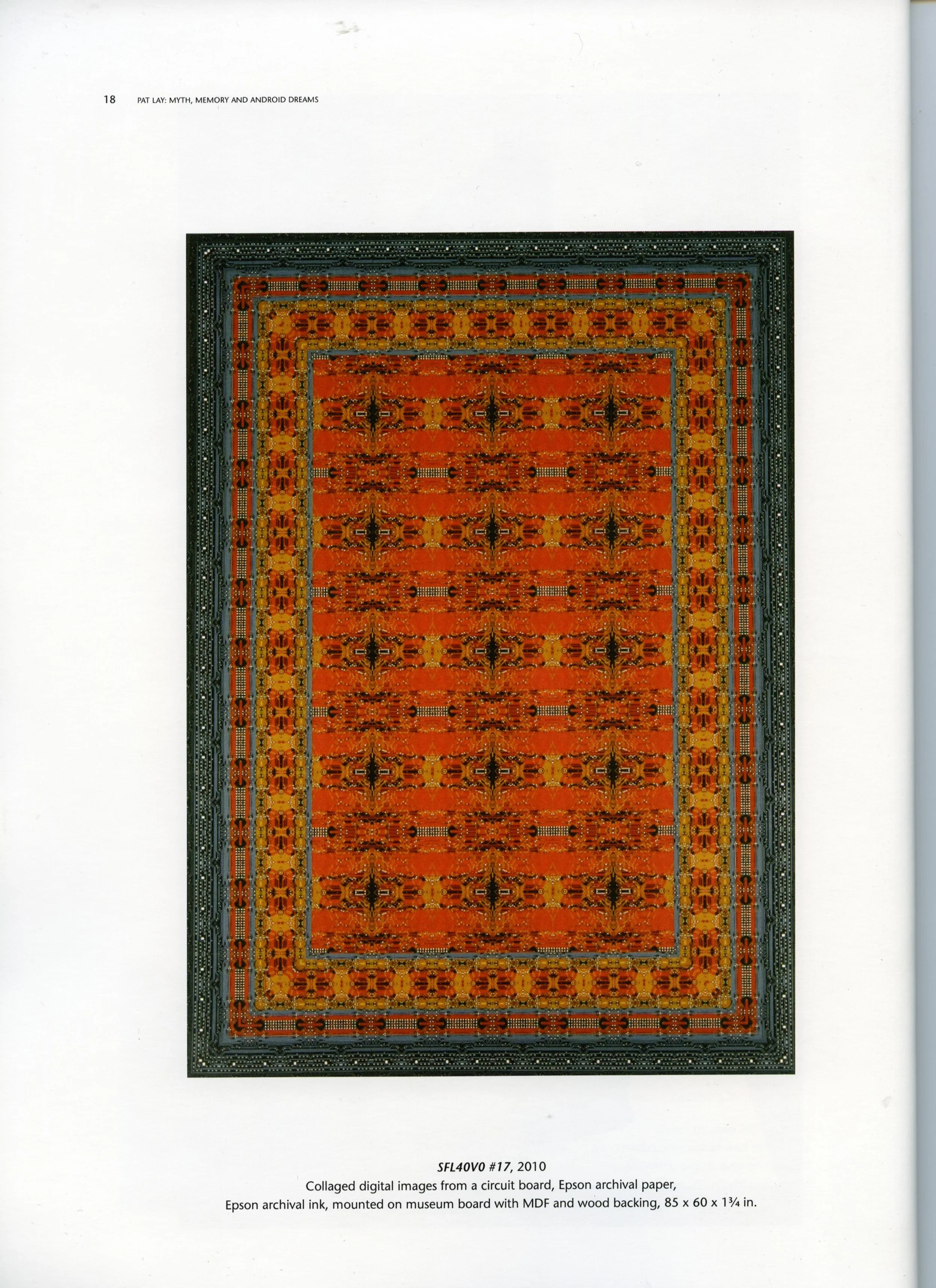

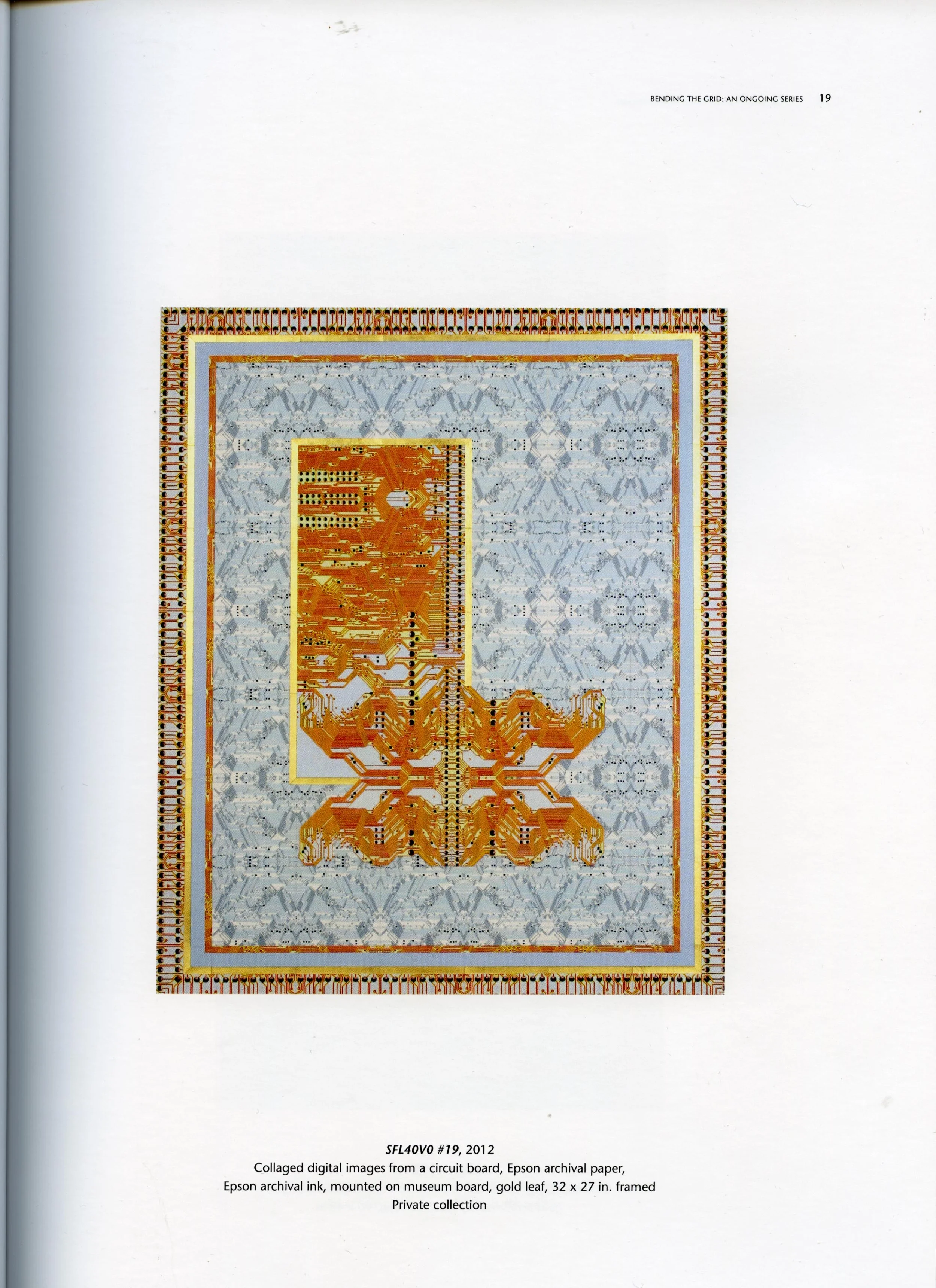

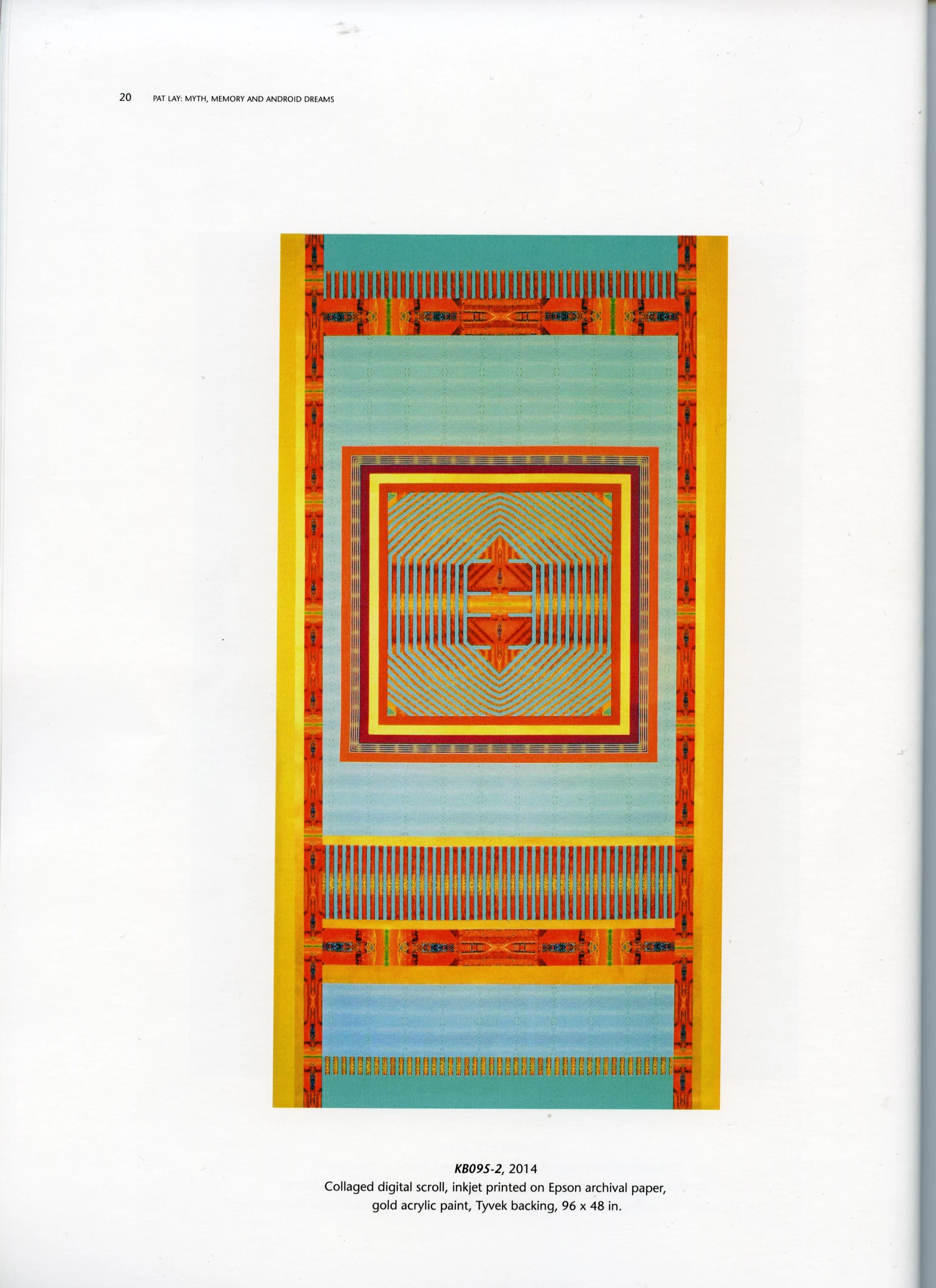

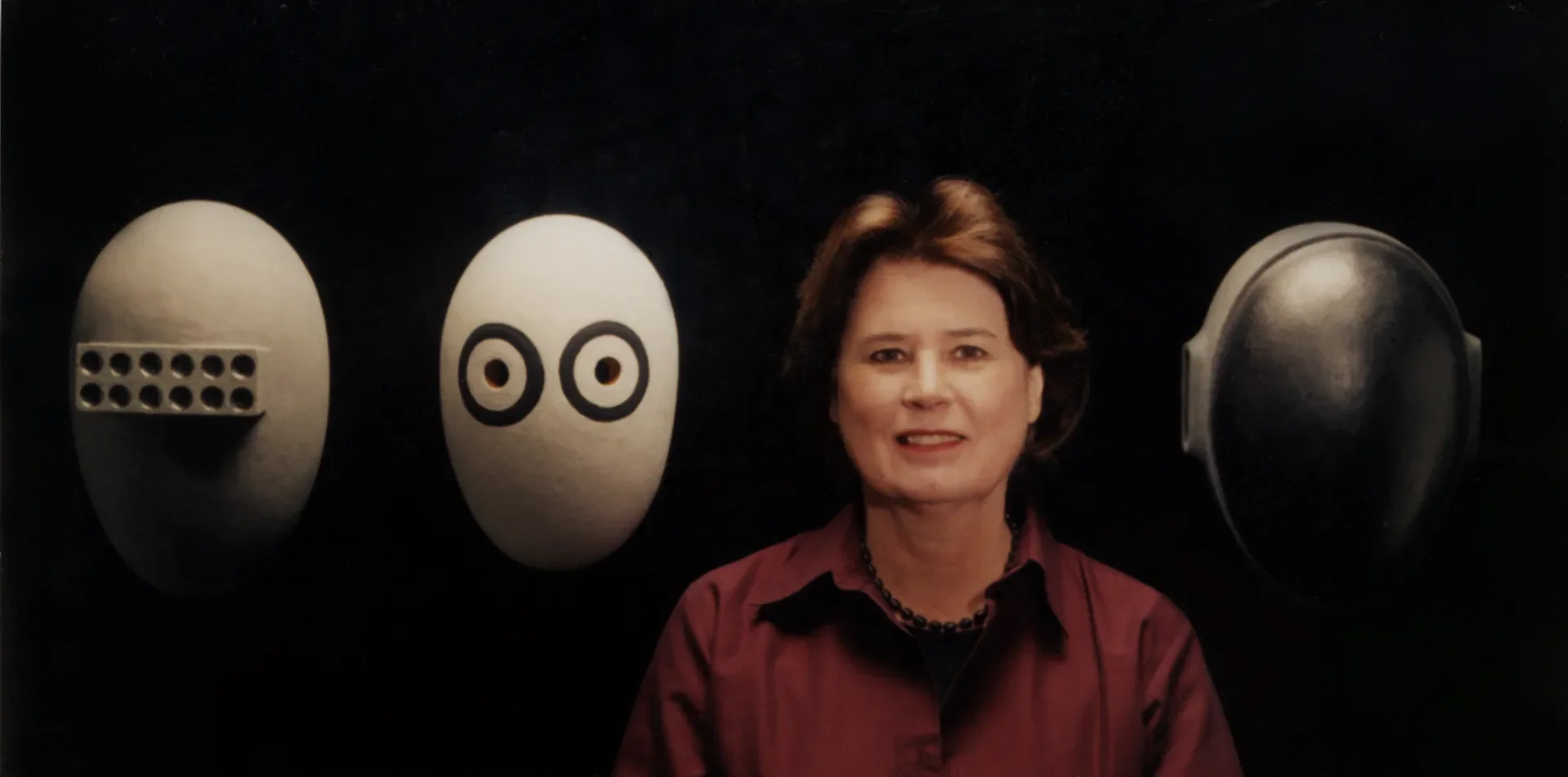

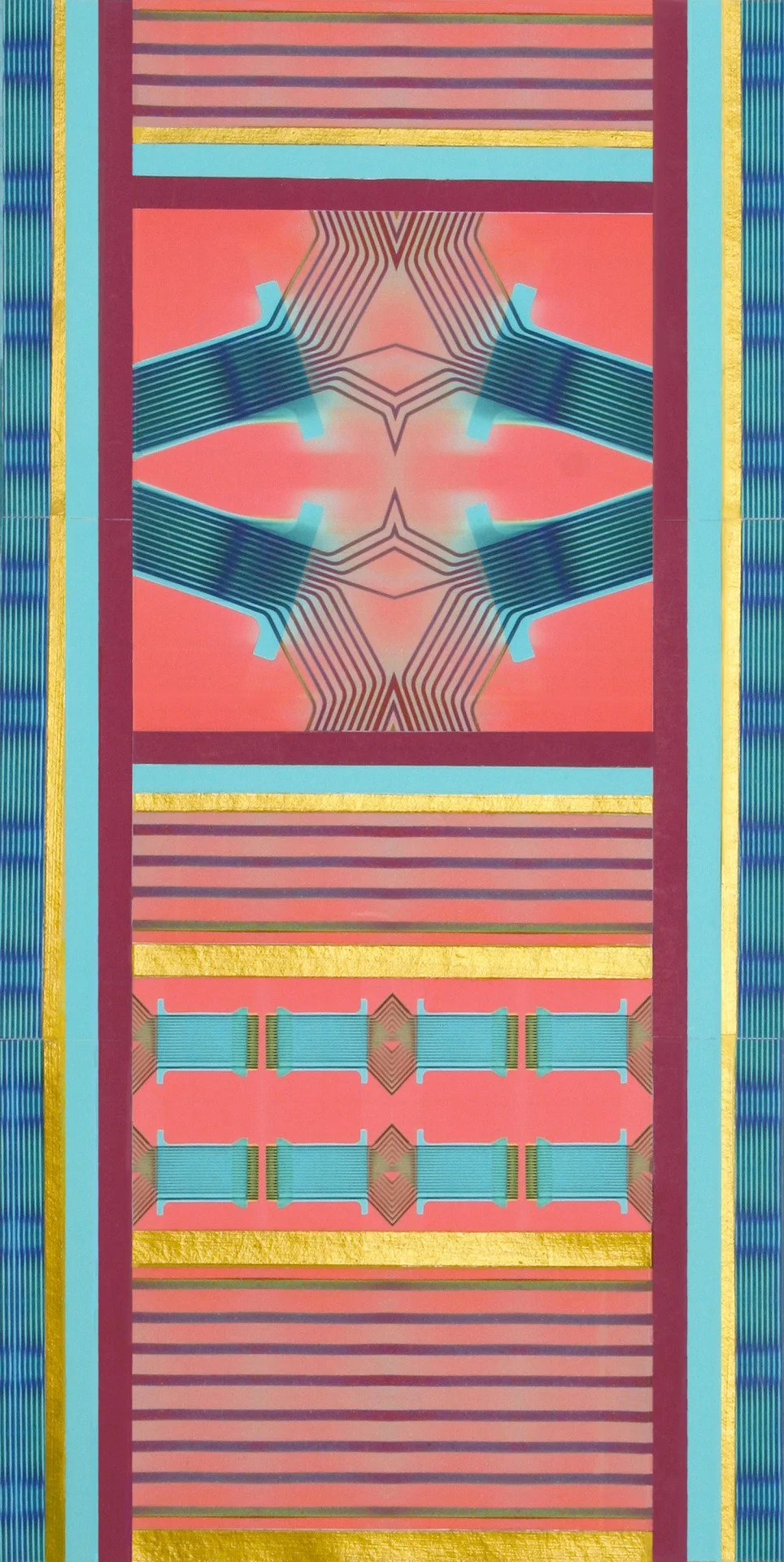

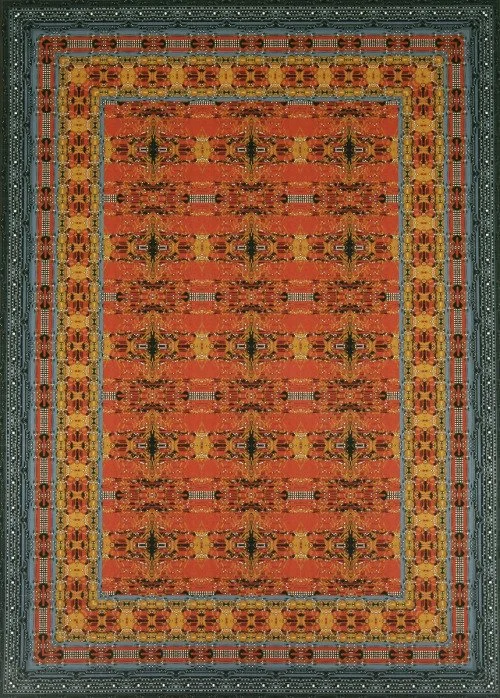

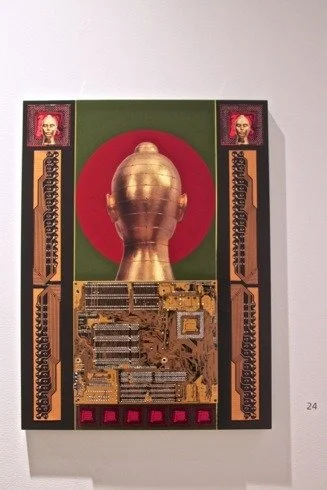

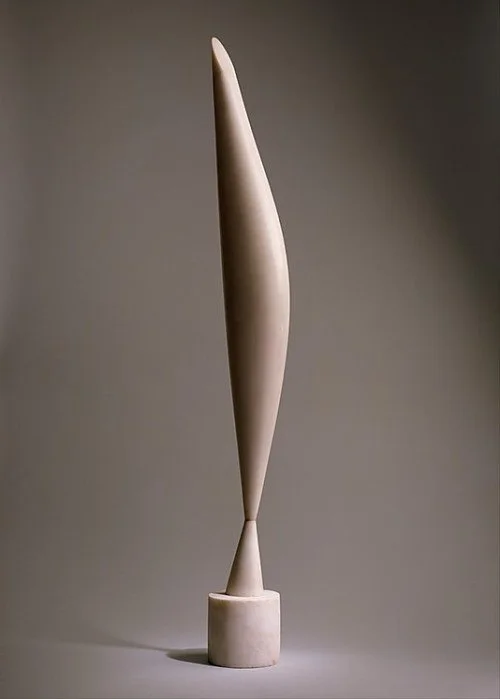

I look to art history for structure and content. In that sense I am a formalist. In the late sixties my fired clay works were geometric, abstract, and concerned with the repetition of form. The Primary Structures show in 1966 at the Jewish Museum was an important influence. In the 1970’s the grid gave to a more open structure. I became interested in the visual discourse between nature and geometry as manifested in the Earth Works movement and formal Japanese Zen gardens. In the 80’s I introduced welded steel in combination with fired clay and incorporated sculptural elements influenced by David Smith and Brancusi. These works were abstract yet suggest a figurative gesture and scale. In the 90’s African and Oceanic art were my primary inspirational sources. Starting in 2000, I combined and hybridized human elements and technology. This work incorporates fired clay, steel, mixed media and ready -made computer parts. In my 2014-15 scroll pieces the structure is formal and incorporates the designs of printed circuit boards. The content, processes, and materials are intrinsically post-modern with the infusion of Persian and Tibetan influences

SIMS: Initiated with that trip you took to Europe with your mother in 1962, you’ve traveled extensively, going in the last twenty years to China, Africa, India, and South America. How have these travels impacted on your work and ways of thinking?

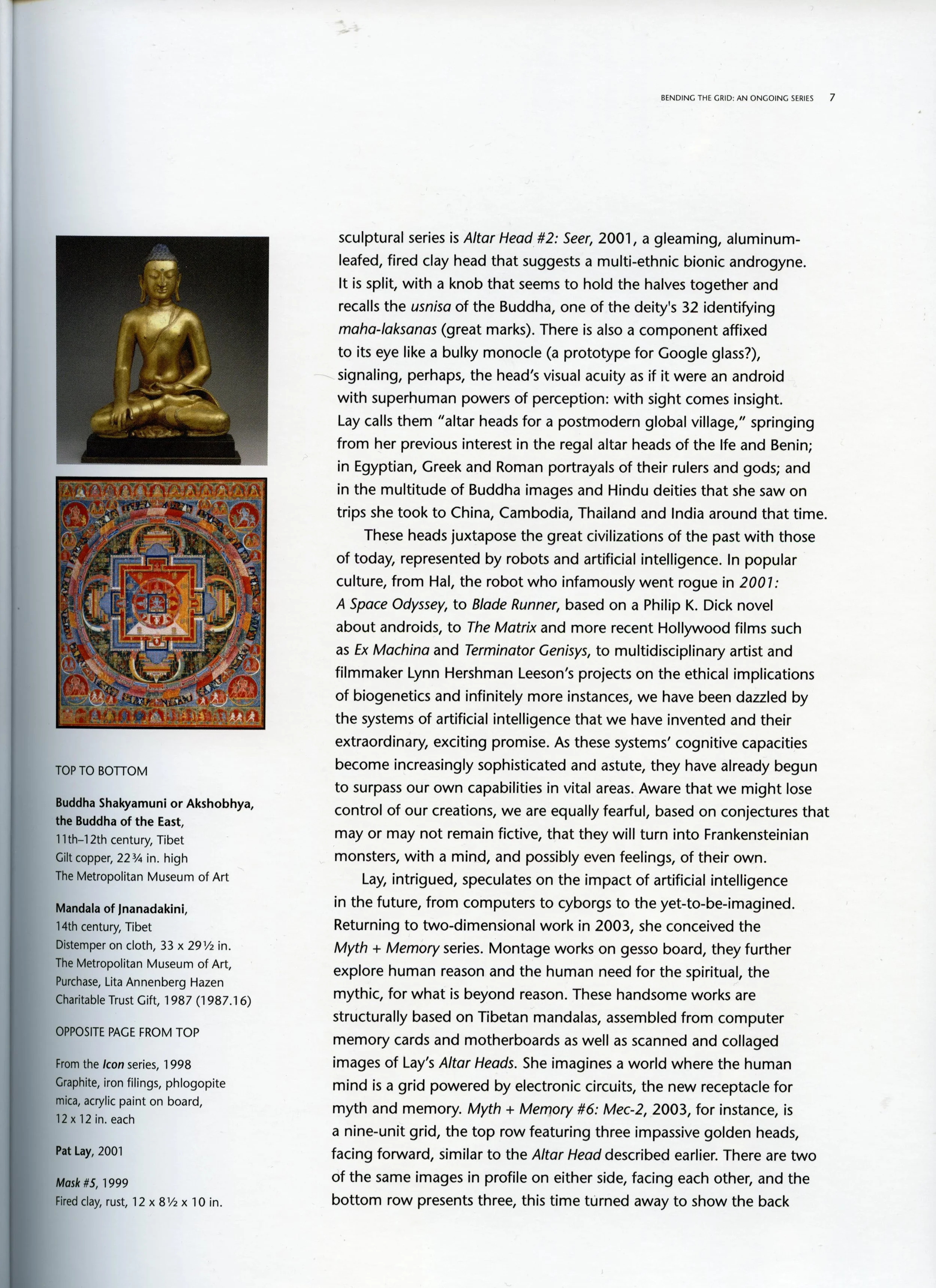

LAY: My European trip with my mother made me realize that to be a good artist it is really important to know the history of art. Now I travel with my daughter. We have focused on visiting Asia, Africa, and South America. We primarily visit museums and historical sights. It is the art, architecture and differences between cultures that influence my work. In Thailand, Cambodia, and India I was struck by the impact and spiritual beauty of Buddha and Hindu deities and in the power emanating from idealized human form. As a result of these trips I started to use the human head as an androgynous, hybrid, post-human form.

Travels to Egypt, Istanbul, Rome, and Peru have added new resource materials to expand my ideas and imagery. The statuary of Pharaonic Egypt, the colors and patterns of the Turkish carpets and tile work, portrait sculptures from ancient Rome, and pre-Columbian clay figures in Peru have had a profound influence on my work.

SIMS: Your travels have clearly opened you to art history and what can be learned in museums. You have not traveled to Tibet, yet Tibetan thangkas have clearly been instrumental to your recent works on paper and larger wall works.

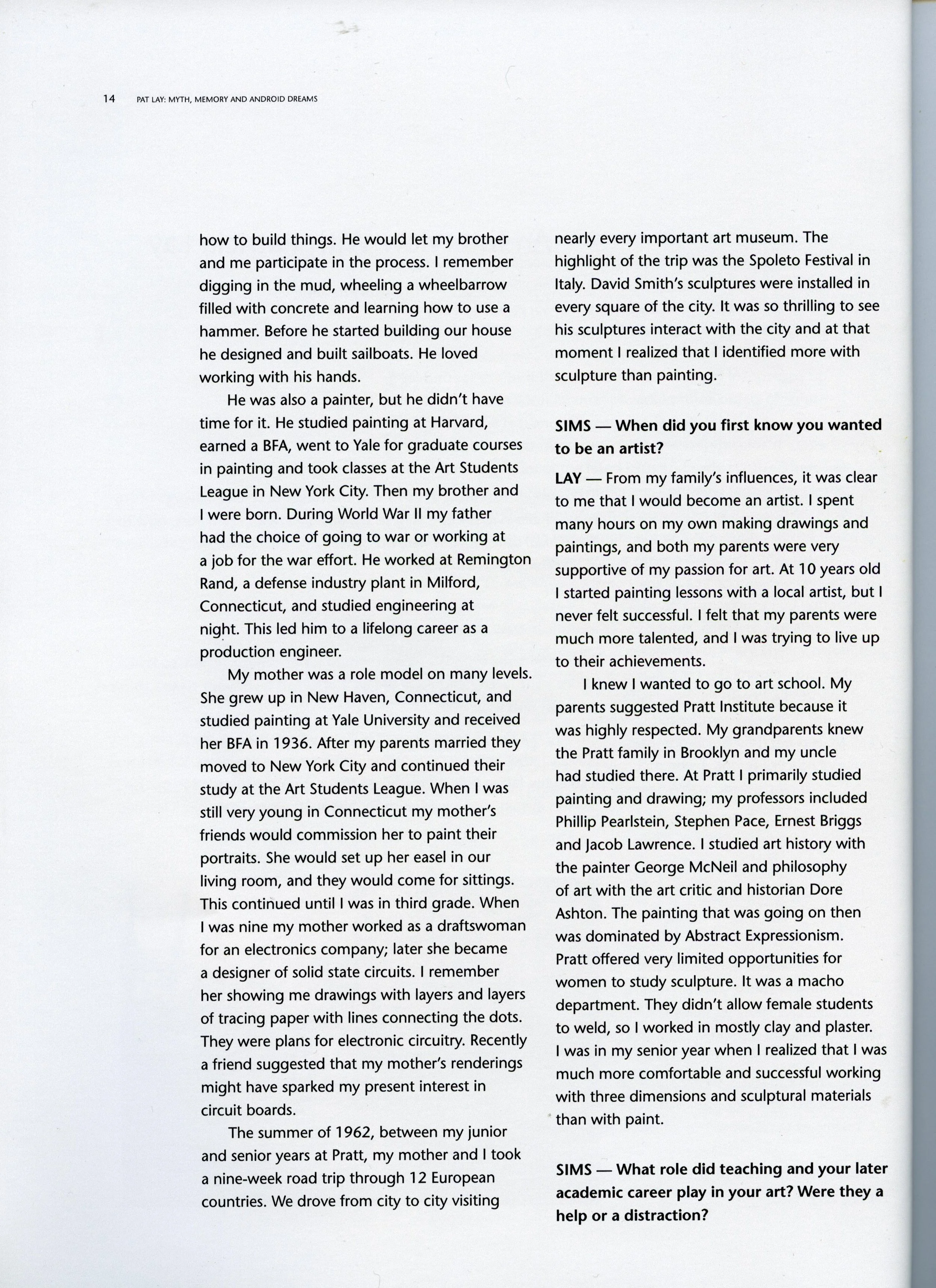

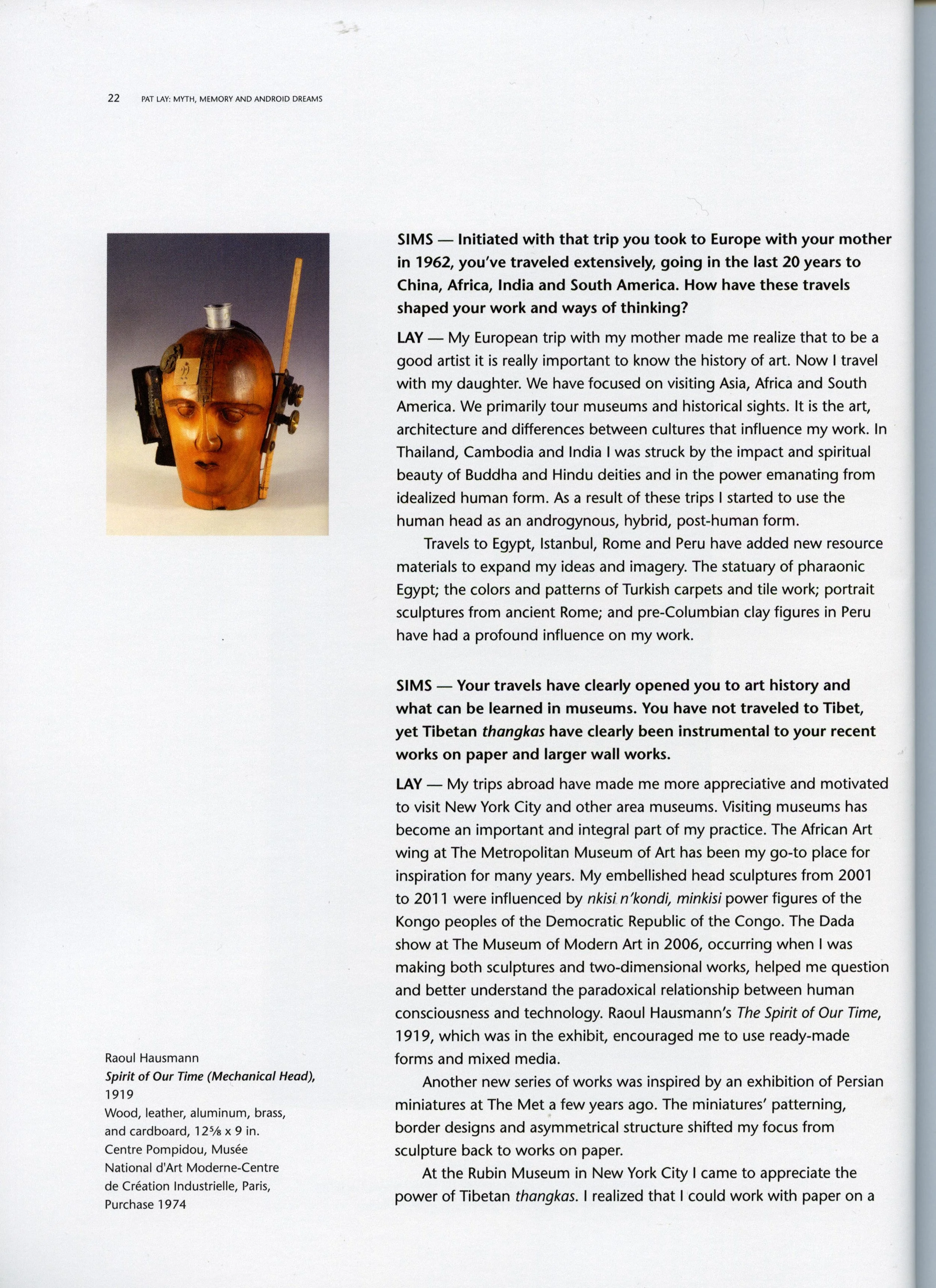

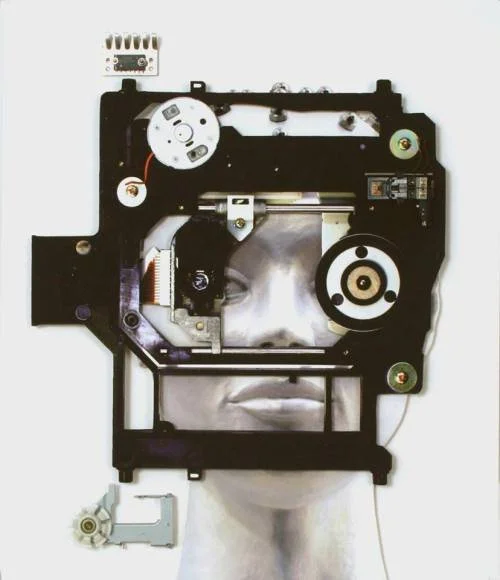

My foreign trips have made me more appreciative and motivated to visit NYC and other area museums. Visiting museums has become an important and integral part of my practice. The African Art wing at the Metropolitan Museum has been my go-to place for inspiration for many years. My embellished head sculptures from 2001 to 2011 were influenced by Nkisi n’kondi/Minkisi power figures of the Kongo peoples of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The DADA show at MOMA in 2006, occurring when I was making both sculptures and two-dimensional works, helped me question and better understand the paradoxical relationship between human consciousness and technology. Raoul Hausmann’s The Spirit of our Time, 1919, which was in the exhibit, encouraged me use readymade forms and mixed media.

Another new series of works were inspired by an exhibition of Persian miniatures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few years ago. The miniatures’ patterning, border designs, and asymmetrical structure shifted my focus from sculpture back to works on paper.

At Rubin Museum in New York City I came to appreciate the power of Tibetan thangkas. I realized that I could work with paper in a much larger scale, up to 96 x 48 inches and turn a religious icon, the Tibetan thangka, into a contemporary aesthetic abstract composition that serenely captures our world of technological advancement. At the same time the scroll format was a practical way to make large works easily portable. Meditating on the past, present, and future, my scrolls and mixed media figurative sculptures question and critique our paradoxical relationship and obsession with technology and what it now means to be human.

SIMS: Many of the artists you mention as influential are men, are there artists who are women you have been influenced by?

LAY: Louise Nevelson was an important role model in the late 1960s when I was in graduate school, as were Eva Hesse, Beverly Pepper, and Barbara Hepworth. More recently, the bound leather mask heads made by Nancy Grossman from the 1960s through to the 1980s have intrigued me and influenced my work

SIMS: Let’s talk more about gender in your work and how that might have played into your artistic practice in the 1960s, 70s and ‘80s, and where you are now on some of those issues.

LAY: I was definitely in a different place in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. I got married in 1963 when I was 21. My husband, the artist Kaare Rafoss, and I felt like we grew up together. We were at Pratt Institute at the same time. While he studied painting at Yale Graduate School, I had a teaching job, and then he taught while I did my graduate studies at Rochester Institute of Technology. We were equal in our relationship. We both had the same degrees, and we both took college teaching jobs after graduate school. We felt very independent and yet shared everything. So there was no gender issue or bias for us. Yet in the art world women and their art were considered less important and respected.

Kaare and I moved to a loft on Broome Street in SoHo in 1969. Soon after that I became a member of a women’s consciousness-raising group. While the women’s movement in New York in the 60’s and 70’s had a political agenda, my focus was on making art that was personal and less concerned with social issues.

SIMS: Are you conscious of aspects of your work that address your gender and address issues of sexuality? Do you think someone could look at your work and say a woman did this work?

LAY: I don’t think my work particularly addresses issues of gender or sexuality. I think it’s very formal. Due to their palette and delicacy, some of the recent scroll works might seem to some people more feminine. For most of my career I consciously tried to make work that was not gender specific or feminine, as I felt it would be dismissed. Now I see male artists whose work looks very “feminine.” It’s just not an issue any more: I and others do what each one of us wants.

SIMS: You talked about being married since you were 21, having a happy marriage, and never feeling in any way that your life is compromised in that relationship or in the bond of marriage. What is it like to not only have parents who are artists, but to have a husband who’s an artist?

Kaare’s artwork is very different from mine, but we’ve also come closer in terms of our art and its characteristics. I’ve learned and taken ideas from him. He’s taken ideas from me. For instance, I’ve been using the grid for many, many years. I went away from the grid for a while, and then I went back to it because Kaare began using it, and it became clear to me that it was a structure that I wanted to work with again. We try to stay out of each other’s studios while we are working. But sometimes I will ask him to critique the work. I also frequently ask him for technical help. We have had opportunities to show together in a two-person show, but Kaare is not interested in doing that.

Recently we have been sharing a studio assistant. Szilvia Revesz has worked for us for about 12 years. Originally she was Kaare’s assistant and in the past six years she has also been working with me on my works on paper. Szilvia is a talented artist with a high level of technical skill and knowledge. She is an essential component of my studio practice.

SIMS: You have lived, worked, and now are having a major career survey in New Jersey: does living and working in the state play any major role in your work?

LAY: I can’t say that New Jersey or its art world per se play a role in my work. We lived on Broome Street in SoHo for twelve years before moving to Jersey City in 1981. We moved to Jersey City when we realized we could afford to buy two connected buildings and an adjoining open lot. It gave us large living and workspaces. It is quiet and has lots of light. We have a garden, which is very important to me, and we can park our car in front of our house. My daughter and her family now live in their own apartment in our buildings. I can go sailing a few minutes away from where I live.

When we moved to New Jersey, I had already been teaching in at Montclair State University for almost a decade. The moment I started teaching and then assuming a more administrative role at Montclair State, where I worked from 1972 to 2014, I was thought of as a New Jersey artist. I had a solo show at the New Jersey State Museum in 1973. I was in a biennial exhibition at the Newark Museum in 1977. In the ‘70s I was submitting proposals for New Jersey’s very active public art commissions program. Forwarding my career was much easier in New Jersey than New York. That went on through the ‘80s, by then I felt I had shown in every museum in New Jersey, yet sold very little art and hadn’t achieved any lasting recognition. So I thought now what?

New York City is the place where things happen. Our friends are all artists, and everything that we do socially and professionally has to do with the art world. For us and others here, Jersey City is effectively NYC’s 6th borough. From our neighborhood in Jersey City it takes us literally five minutes to get to downtown Manhattan. If we have a reason to go to NYC more than once in a day, we do so. I don’t feel like I ever left Manhattan.

SIMS: You have been considering this survey of your work for some time; what have you learned about your art and yourself that you did not know or acknowledge before?

LAY: I have been working on my archives in preparation for this show. It is interesting to see the threads that carry through all of the work. The grid was important to me forty-five years ago, and it is still the structure that I choose to work within now. Another constant is art history, which I have continued to rely on for inspiration.

I have also learned more about my family history and the central role that art and creativity have played. It has all been like putting together the pieces of a puzzle.

SIMS: Given the distinct chapters of your art, as you look back with the organization of this survey, how has your attitude about your work and its developments changed? Do you see unity or disconnection? What has been the impact of having to look back when so often you’ve looked forward to the next chapter of your work?

LAY: Those are hard questions to answer, maybe I will know better when all the work installed at the gallery. I do know that when I get to a certain point with a body of work, that I’m finished with it, and I want to introduce something new. So I look out for what will be the next thing.

SIMS: You probably have had colleagues, artist friends in the New York art world, who have had significant success. It hasn’t seemed to discourage you that you haven’t had that much commercial success. Do you think that economic and critical success strengthens a person or an artist or is not really that important?

LAY: I am confident that I am doing good work, but it is important to me to get some art world recognition. Financial success from selling the work is not so important because teaching gave us a very secure living, we were able to buy in Jersey City the space we need to live and work.

I always thought the ideal situation would be to have one’s art support itself. But financial success can make artists turn their work into a business, and in the process they loose the freedom to change and evolve. People expect certain kinds of work and so you just keep making it. It’s hard to move ahead with new ideas because you can just keep producing and producing.

SIMS: Now that your teaching practice has ended, has more time and the full focus you can have freed or opened up your art making and thinking?

LAY: Yes, I can focus. I don’t feel pressure to rush the work. I have time to experiment. I have thought about working with paper pulp, but I have never had the time to experiment with it. While teaching I felt that I didn’t have the time to deal with the business side of being an artist: self-promotion and networking. I chose to go to the studio rather than promote the work. Family, teaching, and art making always came before self-promotion and socializing. Now I try to structure my time so that more time is allotted for the business of art.

SIMS: How does being older impact on the role that art has in your life and that you now are looking back on the whole span of your career?

LAY: I am not done yet. I will continue to make art as long as I am able. I am happiest when I am working in my studio.

It remains very hard to get a NY gallery, but it’s remains the best way for my work to be placed in collections and preserved.

I would love to say that I would have chosen not to teach and just be a full-time artist, but I know I could not have done that. We have so many artist friends that are in economic distress at this point. They can no longer afford to live in New York City. Many have no retirement income or health insurance. Basic good luck and the choices we made have allowed us to feel financially secure, which makes me feel good about how I have lived as an artist.

Goodman, Jonathan; Sculpture Magazine, September, Review of Aljira Exhibition

SCULPTURE MAGAZINE: PAT LAY (2016)

By Jonathan Goodman

Originally published in Sculpture magazine, September 2016, Vol. 35, No. 7

Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art, Newark, NJ

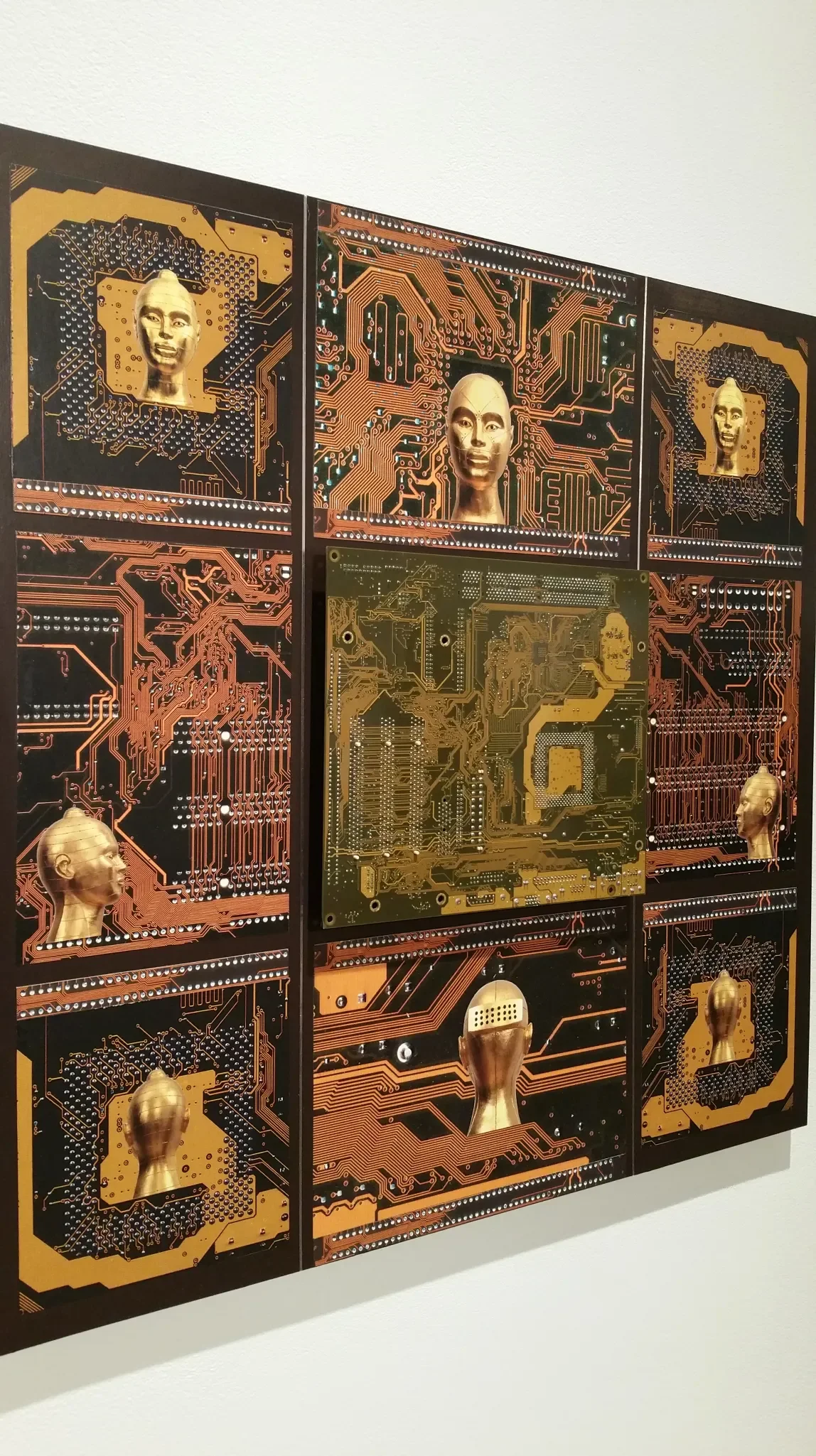

Pat Lay, who retired not long ago from the MFA program she founded at Montclair State University, recently mounted a major retrospective at Aljira, a prominent nonprofit space in downtown Newark. Curated by Lilly Wei, the show covered decades of work, from late-’60s clay pieces to works made as recently as 2015. There was a good mix of three-dimensional work, including archival prints whose exquisite symmetry is constructed from computer-parts imagery, but Lay has acknowledged that the true turn of her work is sculptural.

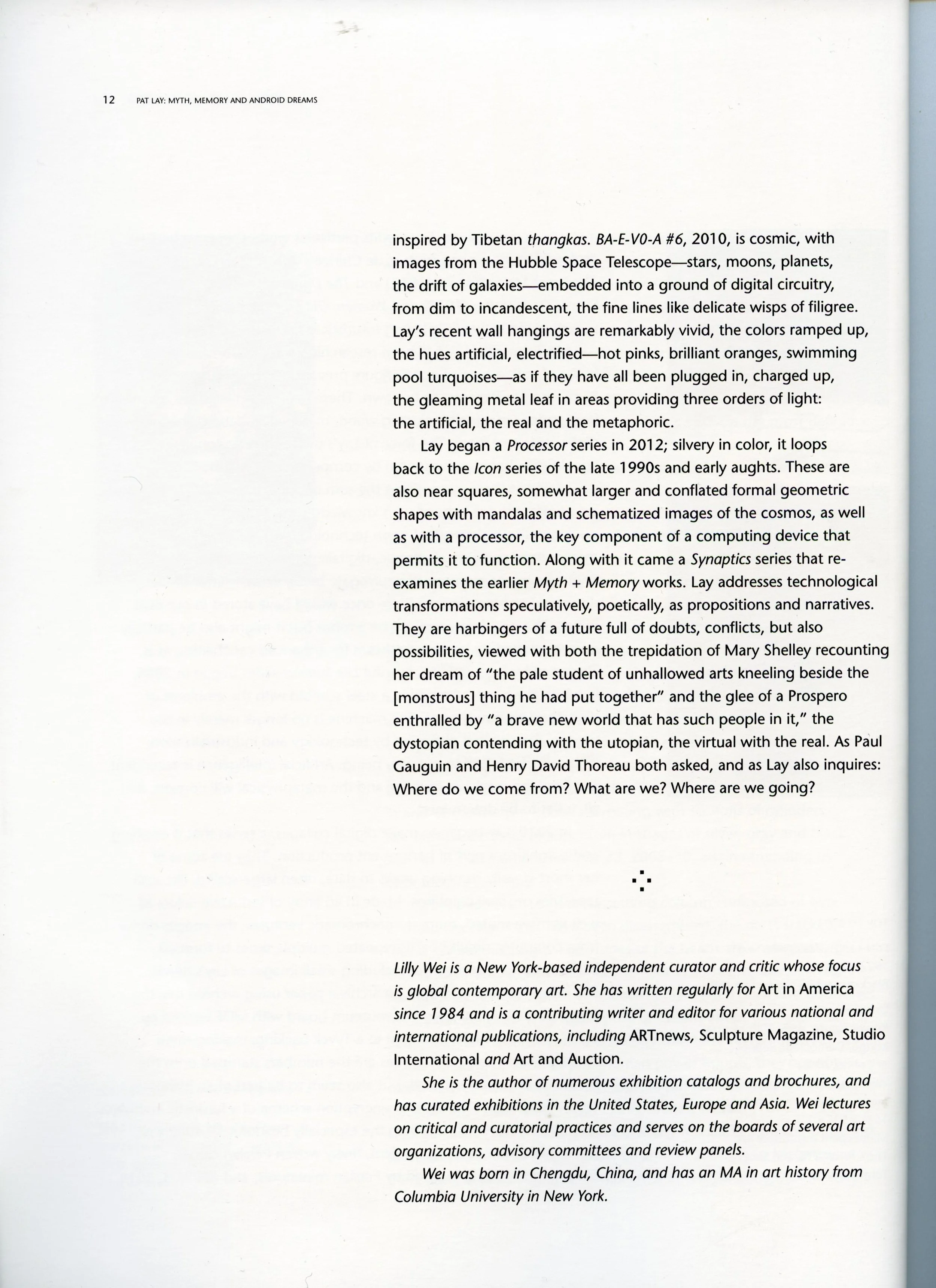

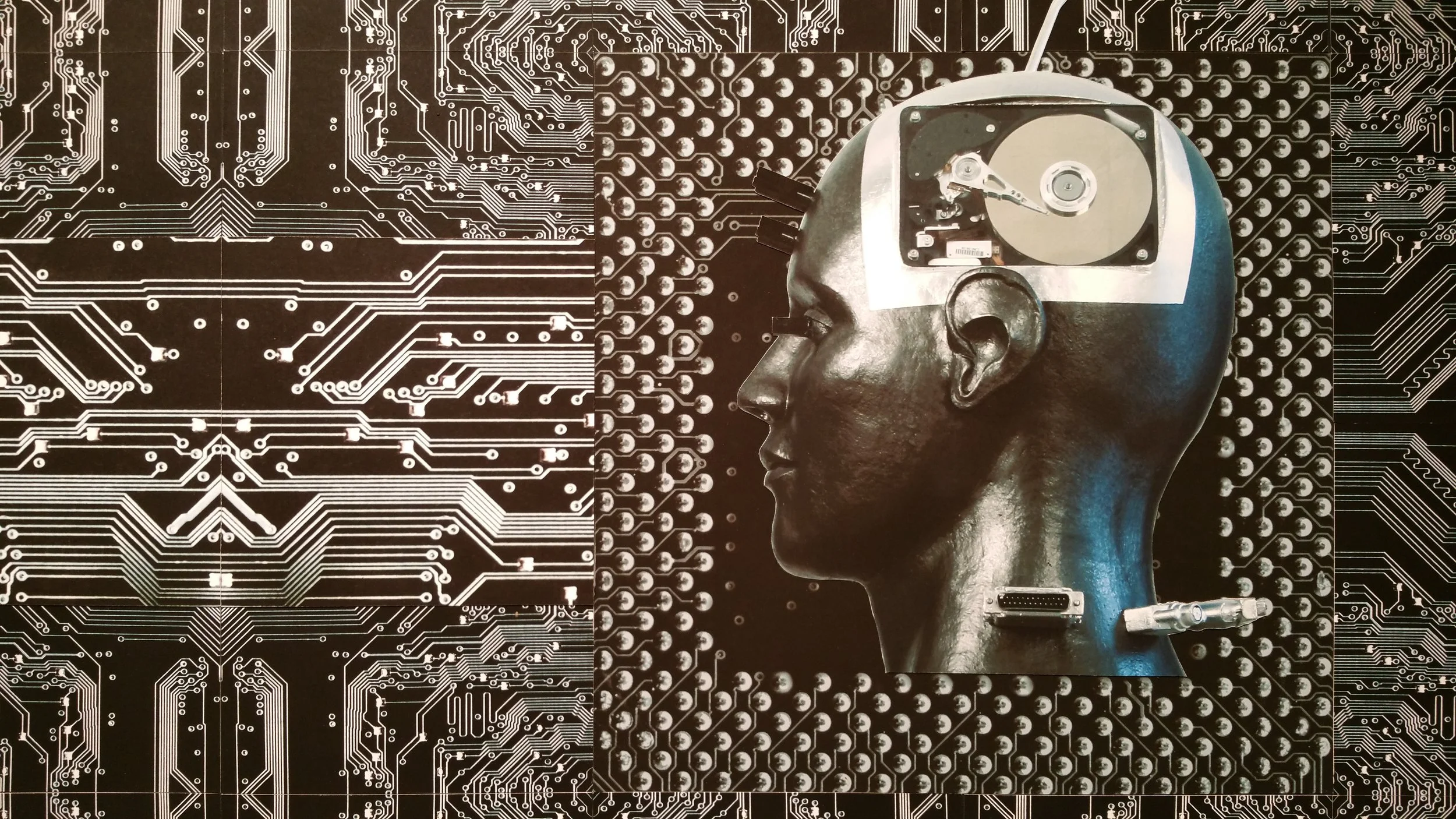

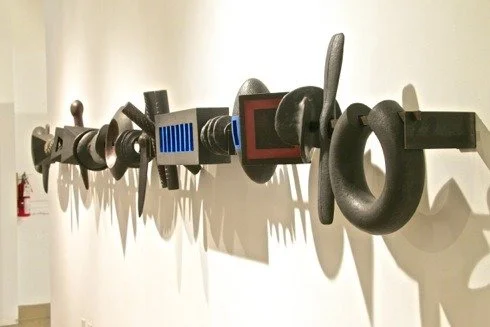

The show included a fine array of three-dimensional objects, ranging from a tile-work installation influenced by Noguchi to African-inspired totems, to gender-ambiguous cyborg heads, from whose crowns issue Medusa-like wires with variously colored wrappings. Lay’s art is endlessly various, which indicates a curious cast of mind. She combines the very old with the very new in ways that push contemporary art forward, toward a statement that covers art history as well as contemporary sensibilities.

An untitled 1975 work, shown in the Whitney Biennial that same year, recalls Noguchi’s sunken garden at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale. Like Noguchi’s garden, Lay’s (smaller) installation has images on top of a flat surface — in this case, a plane made of ceramic tile. A circle of brown cloth, a pyramid, and a translucent box embellish the exterior, complicating the plainness of the surface. Done some 40 years ago, it is strong and independent interpretation of the Japanese sculptor, yet it doesn’t presage the work that Lay would produce in the future.

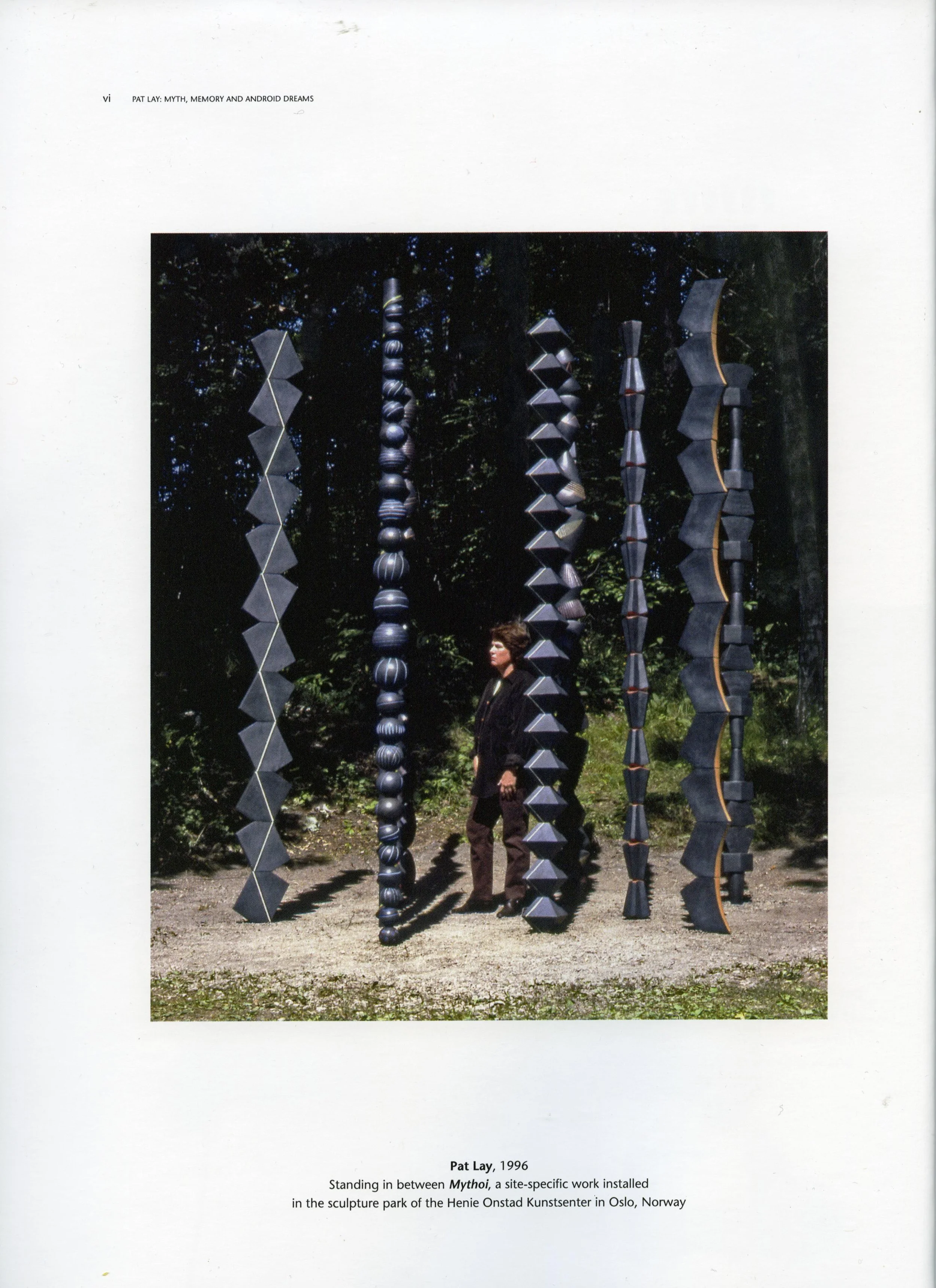

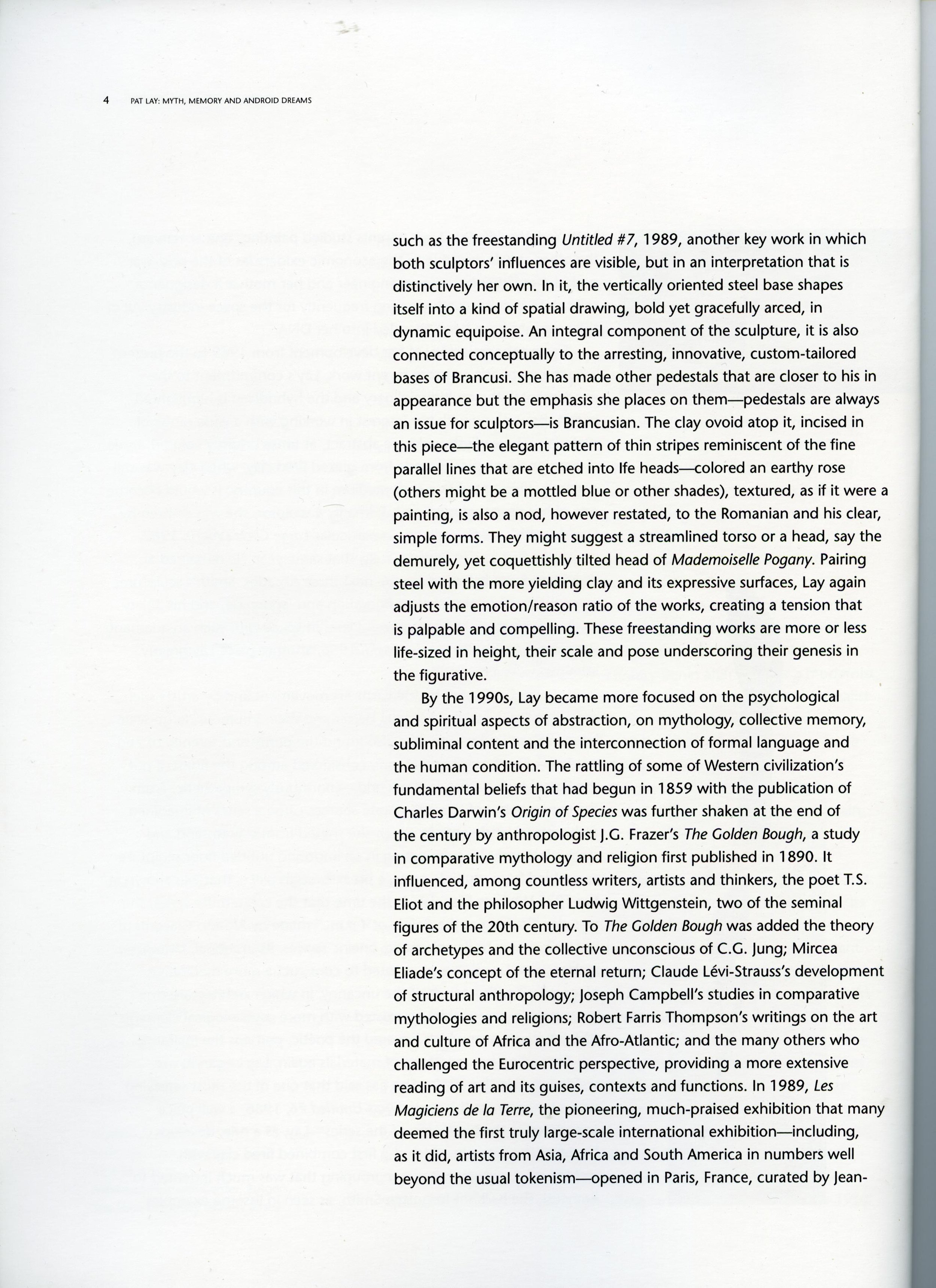

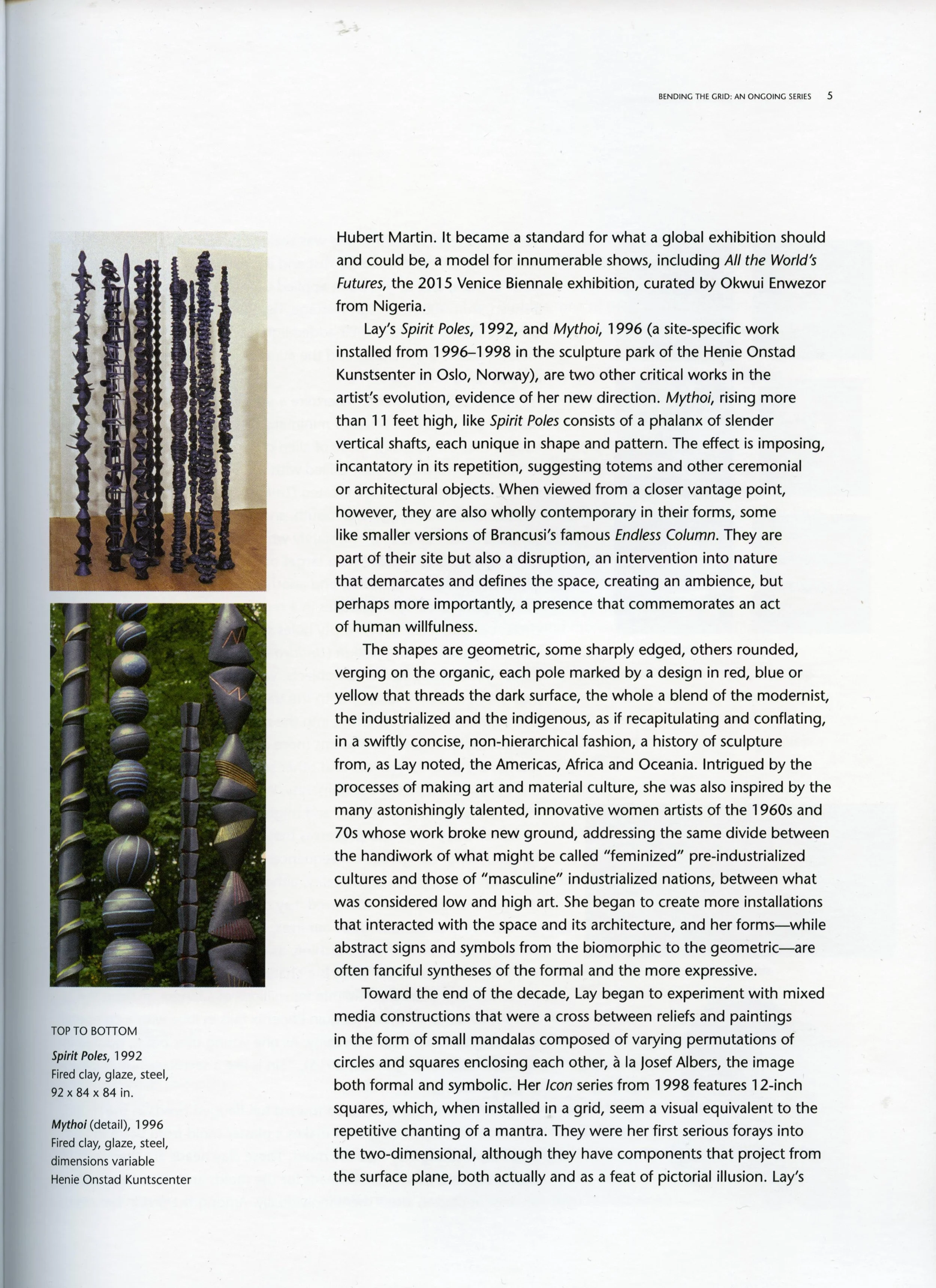

Among her most interesting and strongest works is Mythoi (1996), a group of fired-clay totems, first shown outdoors in Oslo, Norway. Consisting of more than 10 tall, narrow forms composed of repeating elements, the installation looks like a combination of high Modernism and African art. The fusion is genuinely potent. Installed towards the back of the gallery, Mythoi established an atmosphere of ritual power not often found in Western sculpture.

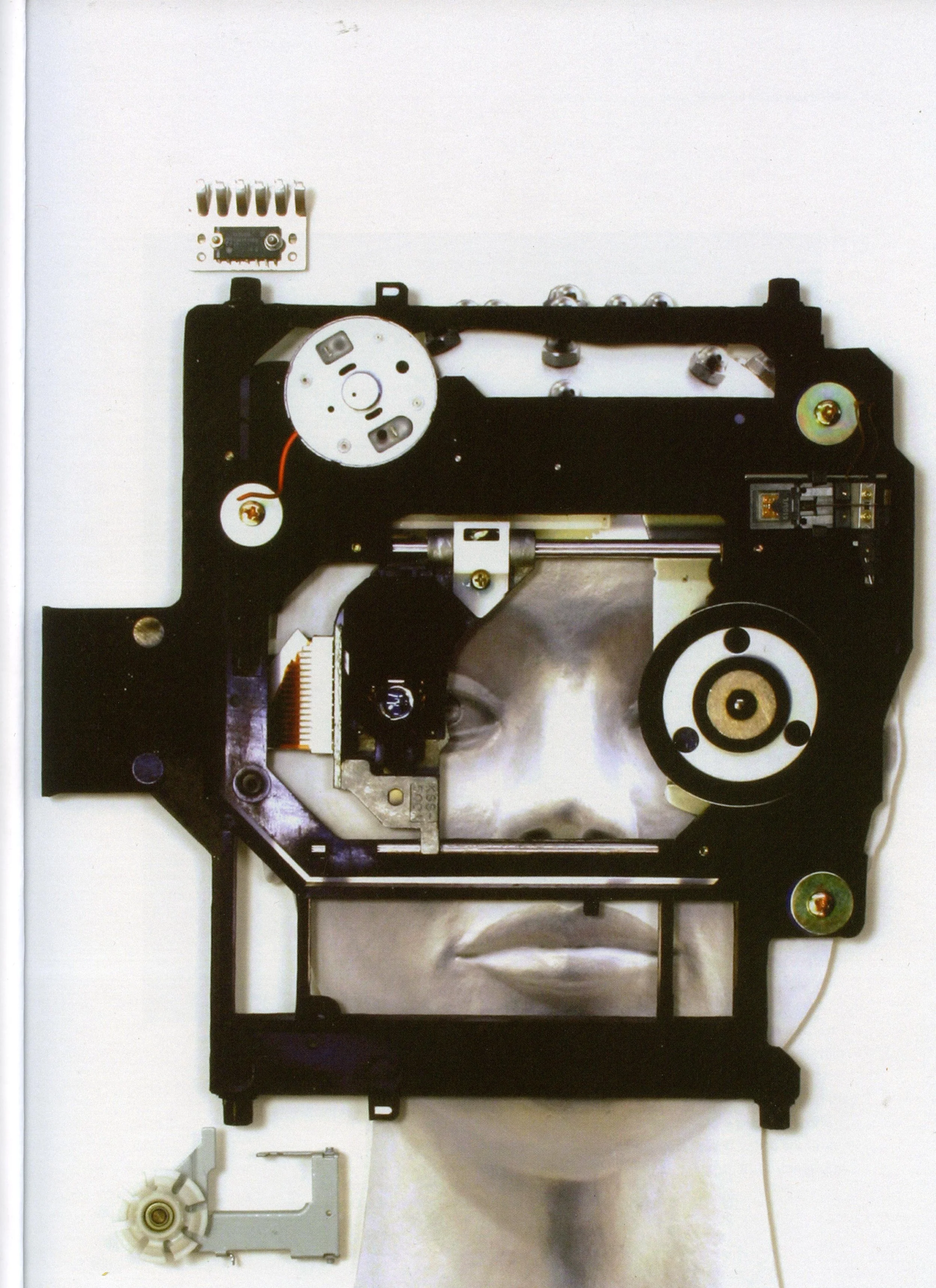

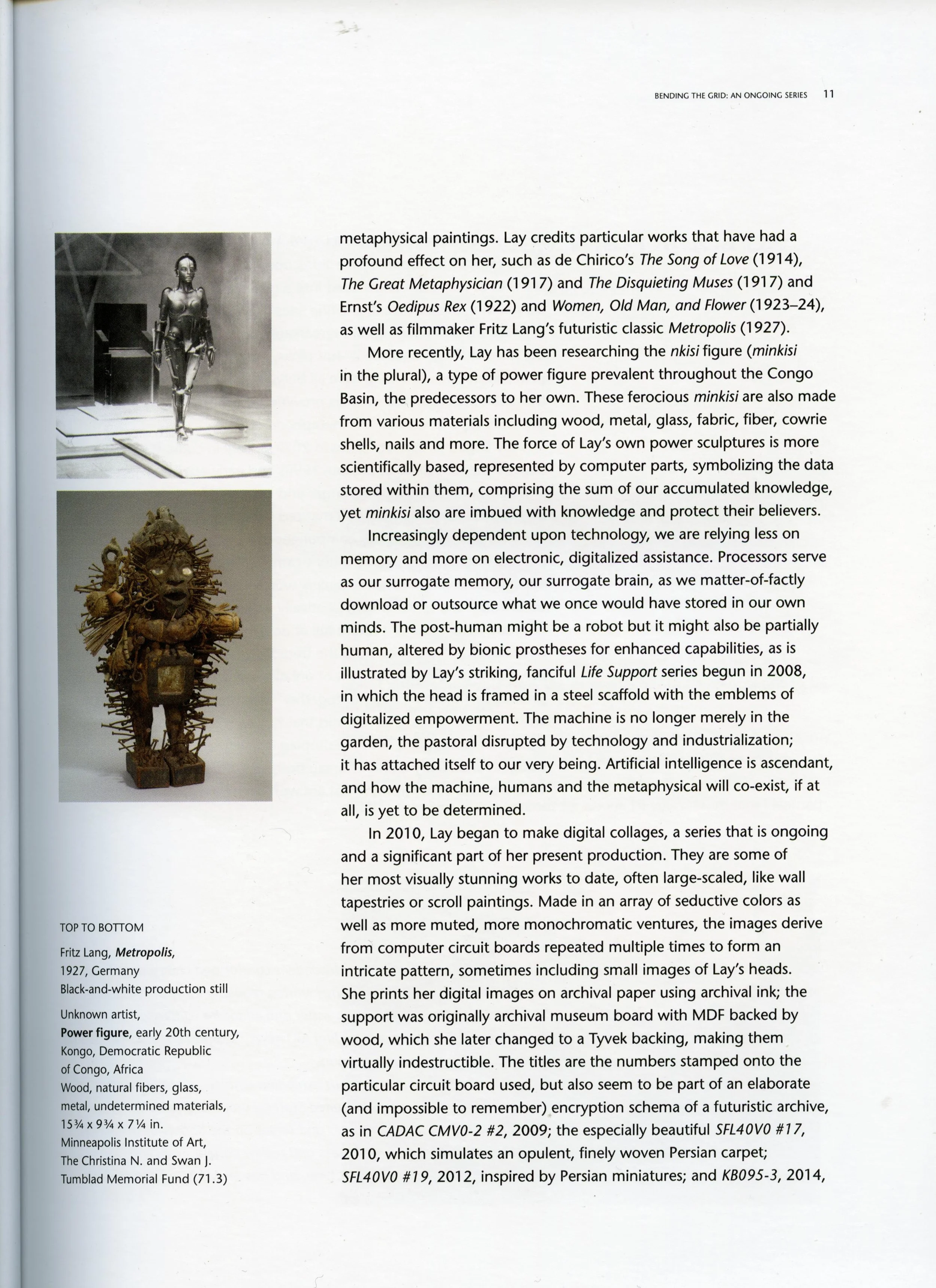

Lay’s high-tech heads have a close precedent in Raoul Hausmann’s 1919 bust Spirit of Our Time (Mechanical Head), which is made of wood, leather, aluminum, brass, and cardboard with various objects. In a similar manner, Lay’s androgynous clay heads are adorned with colored wire and computer parts, as in Transhuman Personae No. 11 (2010). Supported by a computer tripod, the wires fall to the ground. In conversation, Lay has indicated the influence of African nkisi, sculptural objects inhabited by spirits. These nkisi are for spirits of our time. Lay, who began to travel later in life, looks to other cultures for inspiration, successfully transforming influence into resonant statements for contemporary African audiences.

Glover, Tehsuan; Aljira presents: Bending The Grid, The Newark Times, January 21

Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art is pleased to present Bending the Grid: Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams. This major survey exhibition highlights more than four decades of Pat Lay’s career. It presents, for the first time, a broad view of Lay’s expansive vocabulary in a range of various media and styles, influenced by her extensive travels and informed by her overlapping art and non-art interests. The exhibition demonstrates the breadth and prescience of Lay’s vision. It’s very expansiveness – including the combining of art and science – is a subject in itself, as is its tilt toward diverse forms, materials and content.

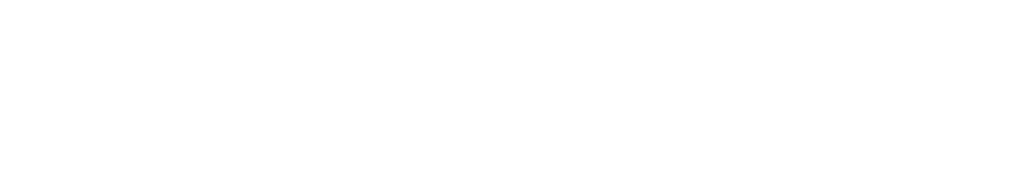

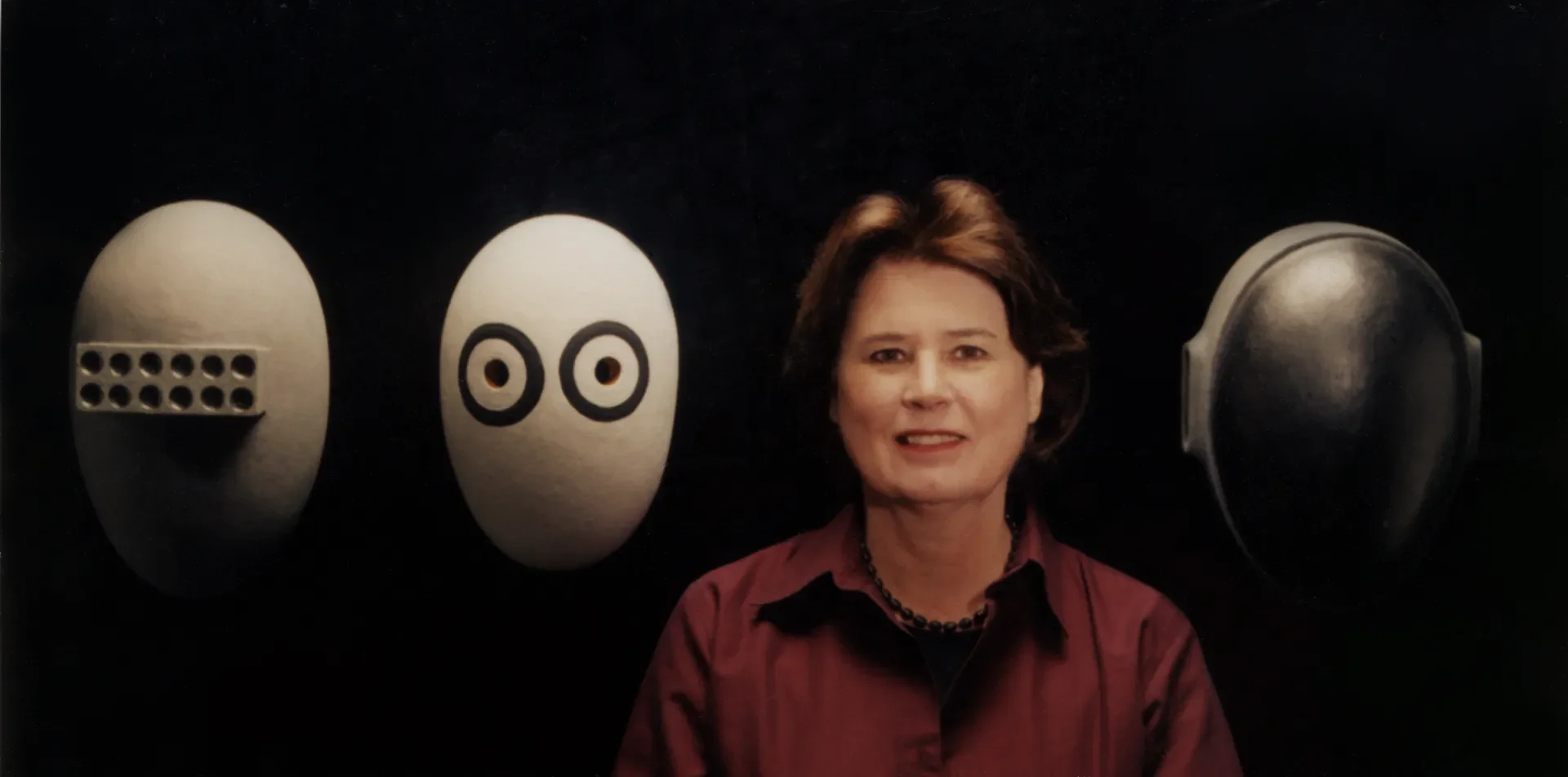

Pat Lay, photo credit: Robert H. Douglass

Tracing the trajectory of her development from 1969 to the present, with the emphasis on more recent work, Lay’s commitment to the experimental, the multidisciplinary and the hybridized is highlighted in this show, along with her interest in working with a wide range of materials. The earliest works are abstract, at times brightly colored, three-dimensional wall pieces made from glazed fired clay, when clay was still generally discounted as a craft medium in this country; it would become one of her signature mediums.

“From the beginning, it seems, Pat Lay has been fascinated by the unfamiliar, by cultures other than her own, especially from distant regions of the world. She was never dismissive of art that was free from European and American formulations, but was intrigued, instead, by its rich, often curious imagery and venerable histories, by its differences,” notes guest curator Lilly Wei. “Lay was also inspired by the many astonishingly talented, innovative women artists of the 1960s and 70s whose work broke new ground, addressing the same divide between the handiwork of what might be called ‘feminized’ pre-industrialized cultures and those of ‘masculine’ industrialized nations, between what was considered low and high art.”

In the past decade Pat Lay’s artwork has focused on technological metaphors of the human experience. Her sculptures, made of fired clay, computer parts and other ready-made elements, are hybrid, post human power figures that have cross-cultural references and question what it means to be human.

Pat Lay Transhuman Personae #11 (detail), 2010 Fired clay, graphite and aluminum powders, acrylic medium, computer parts, cable, wire, tripod 75 x 46 x 46 in.

Aljira’s commitment to Lay is two-fold: first, to make the full range of this artist’s oeuvre more widely known; second, to acknowledge the generous contribution she has made to educating and promoting the work of young artists as a founder of the Master of Fine Arts program at Montclair State University.

Saturday, March 12, 2016, 2–3:30pm:

In Conversation with Visiting Curator Dexter Wimberly:

During this talk, Pat Lay and Guest Curator Lilly Wei will discuss the cultural influences that inform Lay’s work as well as Lay’s commitment to the experimental, multidisciplinary, hybridized works featured in Myth, Memory and Android Dreams.

Bending the Grid: Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams is documented by an illustrated catalog, including an essay by the guest curator Lilly Wei and an interview with independent art curator, writer and chairman of the board of Independent Curators International, Patterson Sims. Three limited edition prints by Lay, donated by the artist to benefit Aljira’s exhibitions and programs, will be available for purchase for a limited time during the exhibition. On sale at shopAljira beginning January 21. The exhibition will be on view at Aljira through March 19, 2016.

A graduate of Pratt Institute and Rochester Institute of Technology, Lay is a retired Professor of Art at Montclair State University. Lay has received two grants in sculpture from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and a grant from the American Scandinavian Foundation. She has been awarded three public art commissions including the installation of a large-scale site-specific sculpture in the sculpture park at the Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter in Oslo, Norway. She has had solo exhibitions at the Jersey City Museum; New Jersey State Museum; and Douglass College, Rutgers University. Her work has been included in group exhibitions in Japan, Austria, Korea, China, Norway, Wales and Slovakia and at the Jersey City Museum, Newark Museum, New Jersey State Museum, The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Montclair Art Museum, The Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Everson Museum, and the 1975 Biennial Exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Lay’s work is featured in a number of books including Lives and Works, Talks With Women Artists, Volume II by J. Arbeiter, B. Smith and Swenson.

Lawler, Anthony K.; Lay with Machines, Not What It Is Blog, February 25, 2016

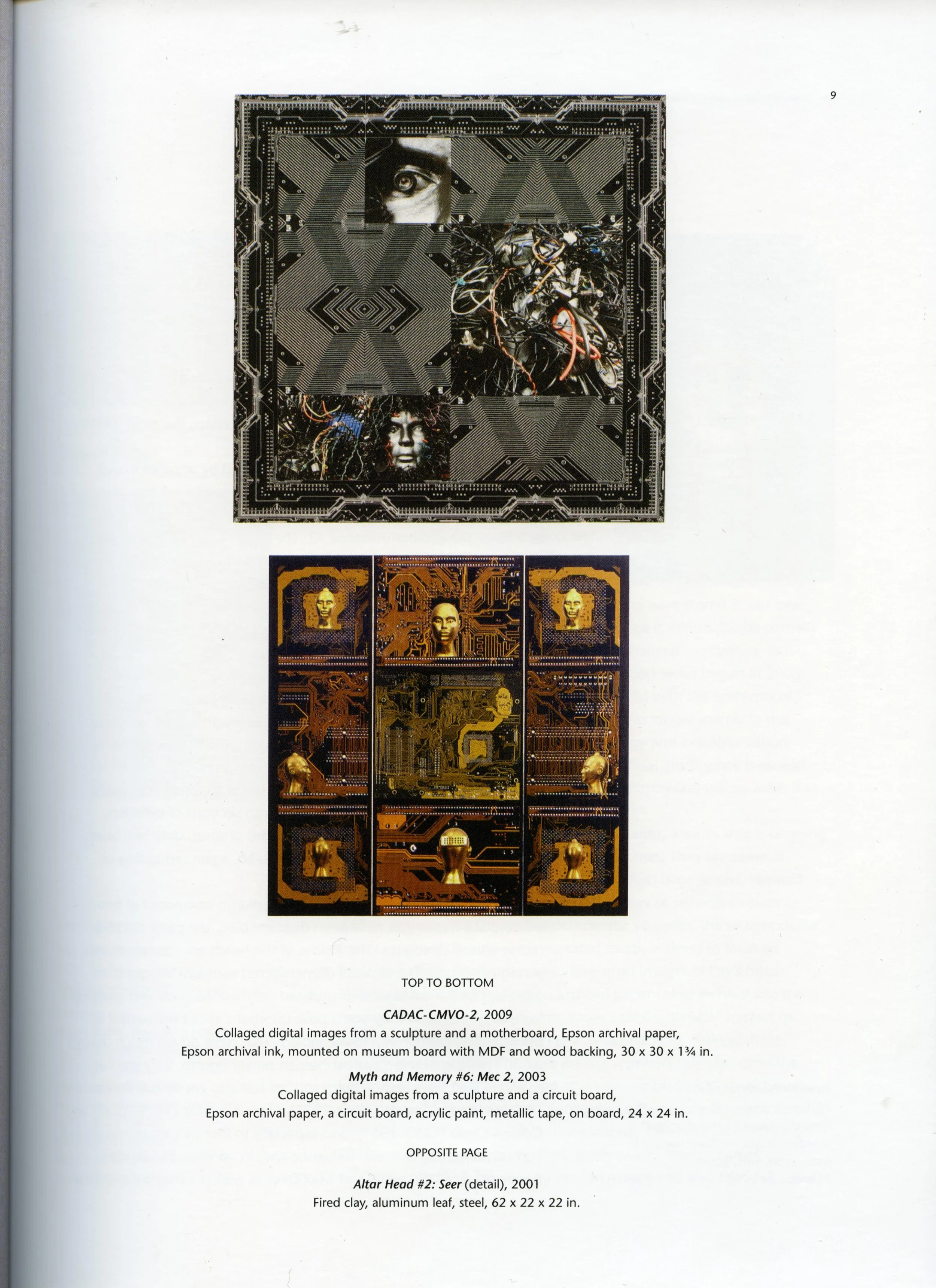

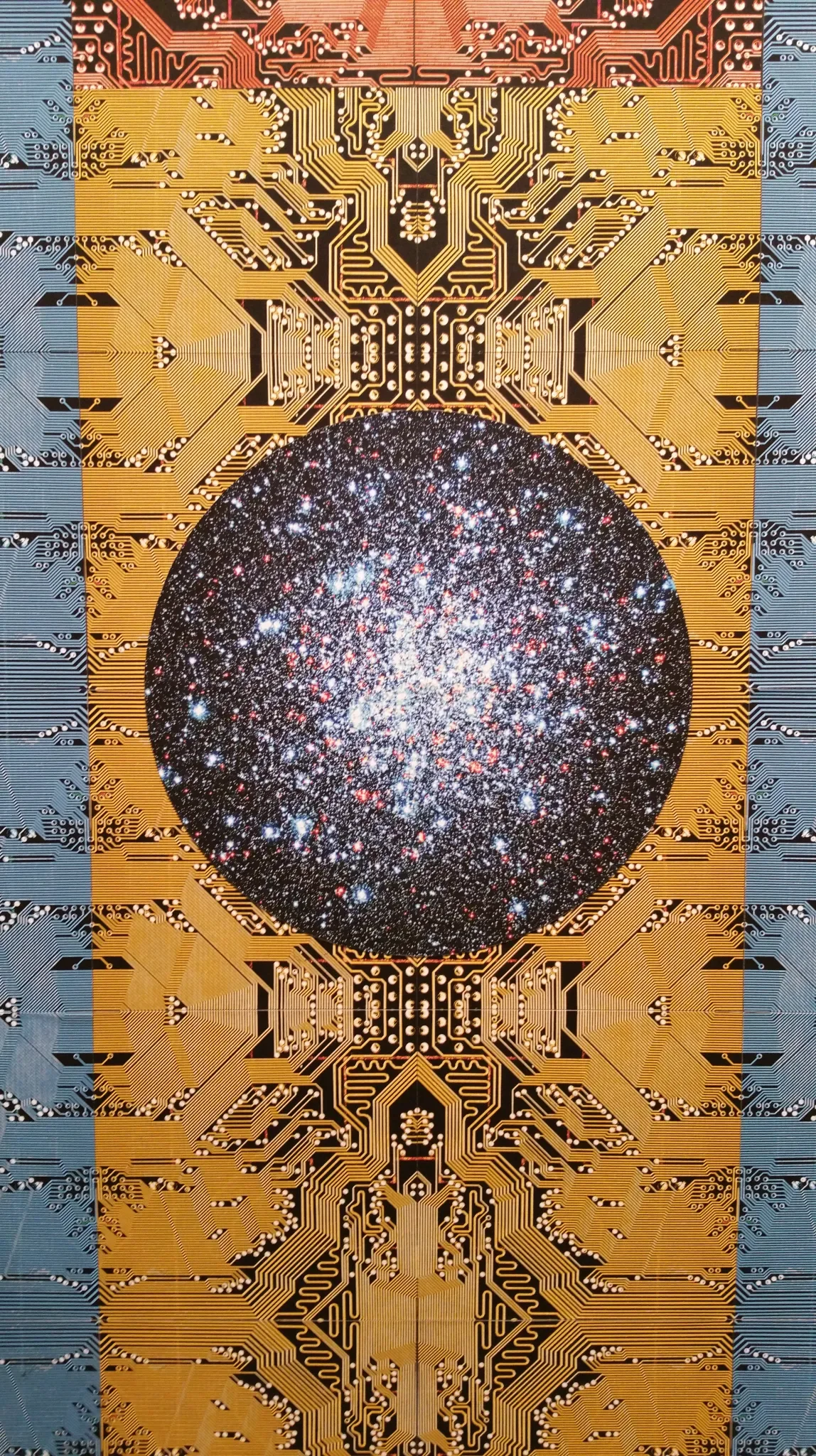

Image: CADAC-CMVO – 2, Pat Lay

A wonderful expanse of creative vision and technological empowerment – a reflection of the rise of our digital age – is currently on display at Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art in Newark, NJ. The artist, Pat Lay, explores in her work a variety of materials, construction methods and thought processes. Aljira’s gallery exhibit is currently displaying work by Lay from the advent of her career in the late 1960’s through and up to the present moment.

Using the patterned line work found in computer circuitry, Lay’s 2 dimensional pieces evoke a mysterious, spiritual and cosmological attachment to technology. The viewer is staggered in their position as each new piece comes into view through the details and meticulous weaving of line and pattern. Several of the pieces are balanced along an axis of symmetry, with one or two elements suspended in a dimension above. Whether digital figures or a view of the cosmos, the juxtaposition of these two entities deliver the work in an interesting and compelling way.

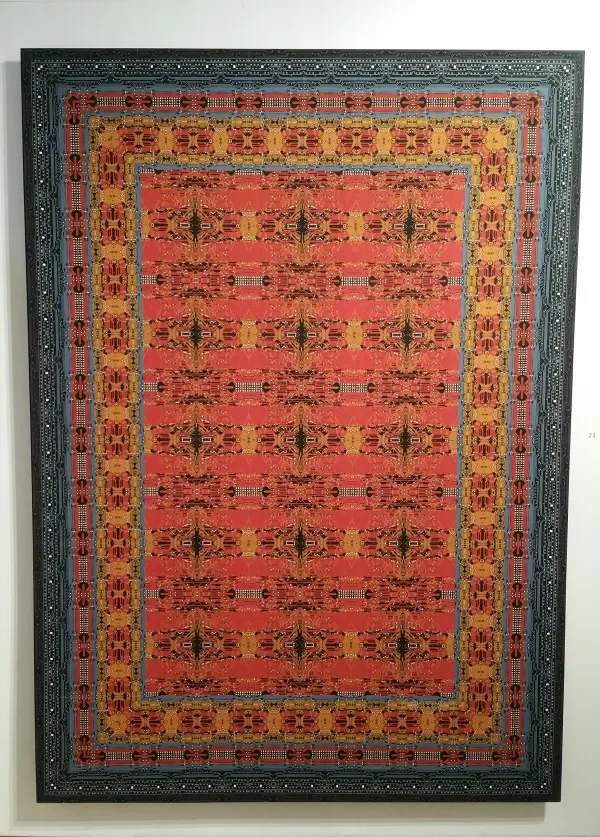

Image: CBA-E-VO-A #2, Pat Lay

Image: SFL40VO #17, Pat Lay

The work jars the schemas of memory by presenting us with familiar icons, such as that of the tapestry, only to realize the details are not of hand stitching, love and thread but instead of wire, electricity and metal. Our human attachment to each piece is thrown into an artificial realm, ushering us toward a new visage of the future.

Each piece is a hybridization of that which expresses our humanity and that which represents the children of our civilization, the machines.

Successors

Lay’s work alienates us, yet draws us in. We are familiar with the forms and elements, yet the non-humanism squirms under our skin. Her android creations are a vision of Transhumanism; they are the product and inevitable conclusion of our tech-society. The emergence of Lay’s machines rises from us, the organics, but settles into an unclear context of whether these geometrics they will express the current values of humanity, or reject them.

Images: Transhuman Personae #6 (left)

Transhuman Personae #1 (right), Pat Lay

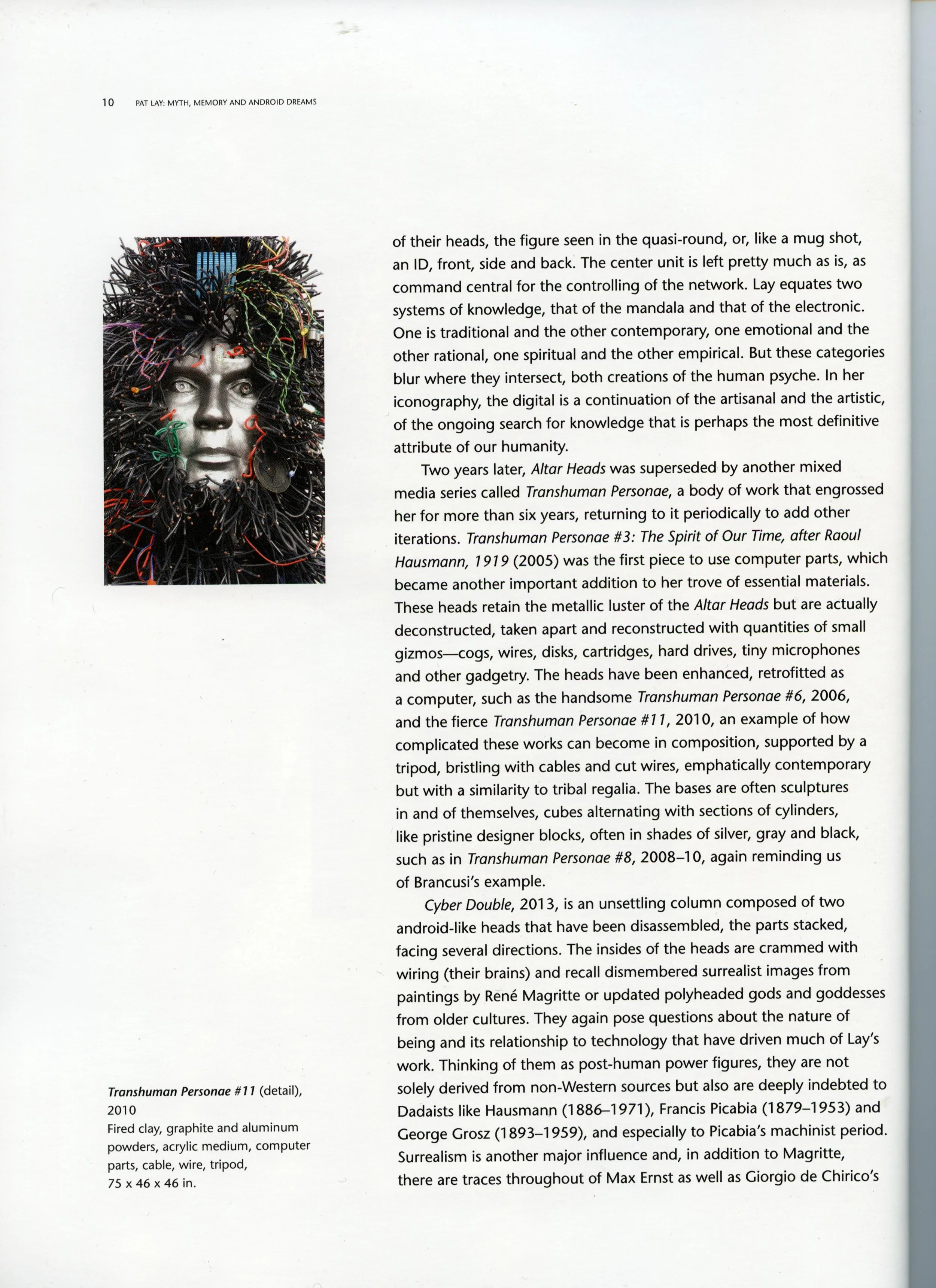

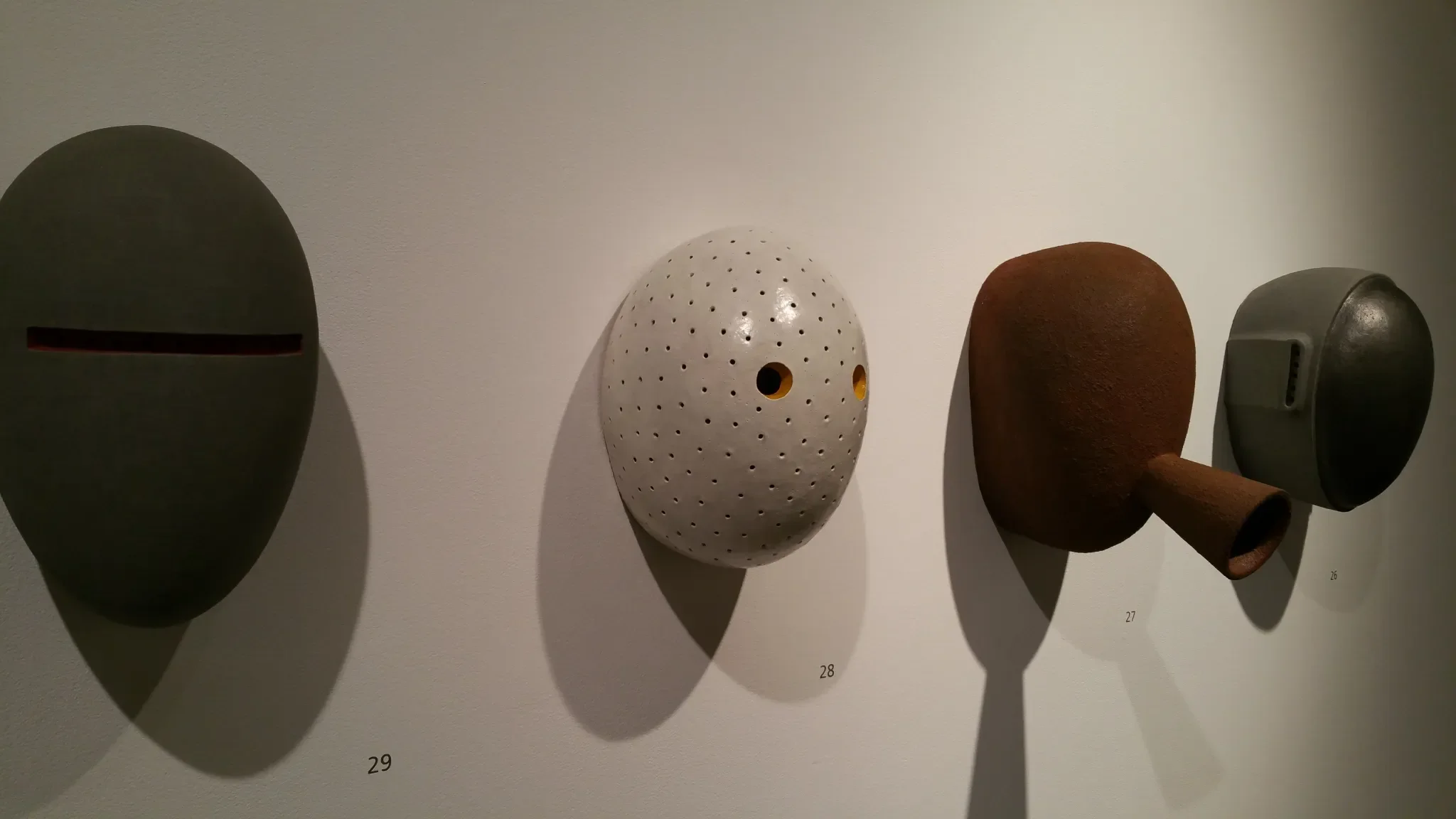

Image: Myth and Memory #6: Mec 2, Pat Lay

The 3 dimensional figures on display balance an interesting harmony between Lay’s early and latter work. This retrospective layout, provides the viewer with a narrative of forms, ones which rise from minimalism and drift into full complexity. Lay’s practice grew during the time of minimalism and the rejection of clay and ceramics as a fine art material. Lay’s ceramic forms function as quiet, yet expressive totems of design and empowerment. The balance between geometric shapes and organic material present themselves with mastery over their forms and the expression of the culture they represent.

Aljira’s guest curator Lilly Wei stated, “From the beginning, it seems, Pat Lay has been fascinated by the unfamiliar, by cultures other than her own, especially from distant regions of the world. She was never dismissive of art that was free from European and American formulations, but was intrigued, instead, by its rich, often curious imagery and venerable histories, by its differences.” I would further add that the narrative in Lay’s work, regardless of medium or context, continues to express her interests in experimentation and the evolution of humankind through form and material.

Image: Spirit Poles, Pat Lay

Image: Untitled, Pat Lay

Image: Mask #1, #6, #5 & #8, Pat Lay

Lay is a graduate of Pratt Institute and Rochester Institute of Technology. She is the founder of the Master of Fine Arts program at Montclair State University, through which her influence and support has bolstered the quality of art in New Jersey nearly as far into the future as her own post-human creations.

The series Myth, Memory and Android Dreams by Pat Lay will be on display at Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art until March 19, 2016. Aljira is located at 591 Broad St, Newark, NJ 07102. For further information on Pay Lay, visit her website at – you guessed it – www.patlay.com or visit Alijra gallery at www.aljira.org

Skorynkiewicz, Kasia; Review: Pat Lay at Aljira, Not What It Is Blog, March 11, 2016

Artist Talk this Saturday, March 12, 2016, 2-3:30pm

Join Pat Lay and Guest Curator Lilly Wei In Conversation with Aljira Visiting Curator Dexter Wimberly

As I walked into Aljira art gallery in Newark, NJ to see Pat Lay’s newest exhibition, I was immediately greeted by a creature standing about the height of a human but made of tripod legs, an abundance of electrical wires, and other computer parts. The only human element was a silver face emerging out of the forest of black cords. Though there was something foreign about this piece it also felt very much familiar at the same time. And that’s when I realized that I just stepped into Pat Lay’s world.'

Perhaps this wasn’t one of Lay’s most important pieces in the collection but it was an indication of what was to come. The gallery was intermingled with wall pieces that were made up of brightly colored symmetrical patterns, which conveyed a sense of playfulness, but the systematic pattern transmitted a rigid and controlled feel. Mixed within these technological components were human elements in the form of silver heads fired from clay that were also composed of more computer parts. And even further into the gallery, the clay component becomes more prominent with many sculptures being made from clay. Though those sculptures seem to concentrate on formal questions, they also seem like they could be creatures that exist in this futuristic hybrid world that Lay is investigating.

I gravitate from on piece to another as if I were a pinball inside a machine, bouncing from one piece to another. Though at first, the pieces seem entirely different, they actually link two worlds together, the past and the present. Lay intertwines the old and the new in a refreshing way. The old is underlined by the use of clay, which still struggles between high and low art. Lay pushes the boundaries of where the human experience ends and where technology begins. Perhaps this hybrid world is our future, where we are interconnected as both human and machine. As a whole, I thoroughly enjoyed Lay’s vivid and hybrid portrayal on the human experience. Whether it is the future world, it’s still a place that remembers it’s past but embraces the future. Pat Lay’s world bends the grid with this exhibition bringing the past, the present, and the future into one interwoven experience.

Spotlight on Pat Lay: Bending the Grid: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams, Aljira Blog, March 8, 2016

Bending the Grid: Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams is a major survey exhibition that presents for the first time a broadened view of Lay’s expansive life and work – in two and three dimensions – in a range of media and styles, influenced by her travels and informed by her overlapping art and non-art interests. In Thailand, Cambodia and India, Lay was struck by the impact and spiritual beauty of Buddha and Hindu deities and in the power emanating from the idealized human form.

Photo Credit: Robert H. Douglas

“By the 1960s and 70s, Americans could no longer maintain a blinkered, isolationist stance regarding the non-Western world. Nor did most want to. How do you keep them down on the farm once they have seen Paree (and beyond) was a question from a popular World War I song. The answer is: you can’t. Our intertwined world continues to grow ever smaller, connected by air, land, sea, and instantaneously, miraculously, by intangible global networks of all kinds – for better or worse,” notes Guest Curator Lilly Wei in the exhibition’s fully illustrated catalog. “Lay, intrigued, speculates on the impact of artificial intelligence in the future, from computers to cyborgs to the yet to be imagined,” writes Wei.

Lilly Wei is a New York-based independent curator and critic whose focus is contemporary art. She has written regularly for Art in America since 1984 and is a contributing writer and editor for various national and international publications, including ARTnews, Sculpture Magazine and Art and Auction, among others. She is the author of numerous exhibition catalogs and brochures, and has curated exhibitions in the United States, Europe and Asia. Wei lectures on critical and curatorial practices and serves on advisory committees, review panels and the boards of several art institutions and organizations.

On March 12, 2016 Pat Lay and Lilly Wei will be joined by Visiting Curator Dexter Wimberly in conversation at Aljira. A fully illustrated catalog with an essay by Lilly Wei and interview with Patterson Sims is available to purchase. Here Pat Lay shares more about the exhibition and her process.

Pat Lay, Lilly Wei and Dexter Wimberly at opening reception (Photo Credit: Akintola Hanif)

ALJIRA: How does it feel to see and present your work spanning so many years in this major survey?

LAY: I’ve never seen it all in one place. Some of the work was stored in my basement and I hadn’t seen it in 30 years. I was hoping everything was still in tact. Seeing the work after 30 years was one thing and seeing it all together was a wow moment.

In the beginning stages, it was really about archiving the work, collecting it with all of the important information I needed: dates, materials, etc. It’s an important thing for an artist to do, because what it leads to is a real understanding of the process and development of the work, how it all ties together from earlier work to later work. You can see the progression. I’ve always told students that they should start their archive right away and just keep adding to it as they make their work. If I’m invited into a show and they say they need photographs and dimensions, I have it.

Working through the technical aspects of the installation process and how things are installed taught me a lot. I learned there are a lot of things I wouldn’t do again. I intend to keep making sculpture but, I think in the future I will make things that are easier to install. It was definitely labor intensive.

It’s really important to work with a curator on a show like this. In putting the show together I had an idea of how I wanted it to be. Lilly had a different idea and she was right. She’s had a lot more experience putting shows together and she’s someone I’ve known for many years. The fact that she’s a woman had a lot to do with my decision to work with her. I wanted more work and she kept eliminating things. She was absolutely right. There are 64 works in the show.

Now that the show is up, it helps me think about what I want to do going forward. For a while, I’m going to make smaller pieces. I’ve gotten very excited about color. I’d like to continue with color and I may be finished with the figurative. My early work is all abstract. At one point I started using the figure. I may be interested in going back to abstract work.

Spirit Poles, 1992, Fired clay, glaze, steel

Untitled #3, 1973, Fired clay, steel, glass, wood, 109 x 86 x 12 (Installation Photo: Arlington Withers)

Untitled #3, 1973, Fired clay, glaze, sand, 17 x 17 x 4, New Jersey State Museum L.B. Wescott Collection (Installation Photo: Arlington Withers)

Anthology, 1996, Fired clay, glaze, steel, 92 x 84 x 84 (Installation Photo: Arlington Withers)

ALJIRA: What was the process for making the benefit prints and the digital collage work?

LAY: The benefit prints are based on the larger scrolls and I was excited to do them. The actual printing was done by Szilvia Revesz. She’s been our studio assistant for about 12 years. She’s primarily interested in works on paper and printing techniques, so this was right up her alley. The benefit prints are digital and silkscreen. There are three screens; two colors plus a metallic and then the digital. It starts with a digital image, then we put the screen colors over that. I was excited about the metallic screen printing ink in them, too. The copper, silver and gold have a very beautiful quality to them. The large scrolls are not something that can be framed and they are kind of vulnerable. Sometimes taking the idea to a smaller scale makes it easier to handle and more sellable. Because the prints are small I can just keep making them. It’s a way of working that feels like I could keep going. It’s the first time I ever made prints. It’s something I always wanted to do and I never had the opportunity or reason to do it. This was it.

The digital works like “SFL40V0 #17″ are collaged together or tiled. They’re squared and the edges are borders. It’s made of lots of little parts. It’s easy to print them since I have a 13 x 19 printer at home. The beauty of collage is you can move them around until you get what you want. I had the pieces on my floor and just kept moving the pieces around until it made sense. People ask me: “why don’t you put it all together on the computer?” I did that with the prints but the thing I like in the larger pieces, like the scrolls, is the handmade quality of it. They show the hand and the process.

Much of my process is just intuitive. A lot of it is play, which is a really important word in my work. Playing with the materials and letting things happen. Seeing what the materials want to do.

KB095-3, 2014 Collaged digital scroll, inkjet printed on Japanese kozo paper, gold acrylic paint, Tyvek backing, 96 x 48

SFL40V0 #17, 2010, Collaged digital images from a circuit board, Epson archival ink, mounted on museum board with MDF and wood backing,

85 x 60 x 1 ¾

Myth and Memory #7, Elpina, 2003, Collaged digital images from a sculpture and a circuit board, Epson archival paper, a circuit board, acrylic paint, metallic tape, on board, 18 x 24

Transhuman Personae #11, 2010, Fired clay, graphite and aluminum powders, acrylic medium, computer parts, cable, wire, tripod, 75 x 46 x 46

ALJIRA: Where did you find the wires and materials for Transhuman Personae #11? What was your process like?

LAY: It’s mostly cable wire. I was following the cable guys around in their truck and asked if they had any scraps. One guy led me to an industrial area in Jersey City where they work. They had a big dumpster where they threw away all their scraps. One of the cable guys there went into the dumpster and started pulling stuff out for me. I also used electrical chords and telephone wires. When I started using computer parts, though, I couldn’t figure out where to get them. I finally sent out an email and asked people to send me their old computer parts. But at first, I went to Techserve, since they rebuild and fix computers, and I asked them what they do with their old parts. They told me they had a dumpster and I could come by. So, I was dumpster diving. Then people started just giving me stuff. Now I have more old computers in my studio than I know what to do with.

Life Support #14, 2008, Digital assemblage, Epson archival paper, Epson ink, computer parts, archival foam core, museum board, 22 ½ x 20 5/8 x 2 ½

Untitled #1, 1986, Fired clay, steel, clay slip, 12 ½ x 29 x 3

ALJIRA: The use of clay has a stigma that it is material suited more for craftmaking than for fine art. Are you reversing that stigma in your work?

LAY: I think that throughout my entire career I have tried to bring clay out of craft. I’ve always wanted it to be taken seriously as a material for sculpture. It has certain properties the way wood and metal have properties. Of all the materials for sculpture, clay has the most versatility. It can go from organic forms to geometric forms. I think the stigma that clay is a craft material is changing. It’s still there in certain groups but I think it’s not the issue that it was by any means. Clay is taken much more seriously.

In the very beginning I figured out the way to be taken seriously as a sculptor using clay was to combine other materials. So clay and steel are taken more seriously when used together. It’s much more interesting than having the whole thing made out of clay.

I was interested in learning how to weld. The imagery comes from Brancusi who I was inspired by. The most important thing was that I was learning how to weld combining clay and steel.

Installation, Photo Credit: Arlington Withers

Constantin Brancusi, Bird in Space, 1923, Marble sculpture, 56.75 x 6.5 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art

ALJIRA: In your practice have you been continuing your formal investigations in a different way through each of your various works over the years?

LAY: I’ve always been interested in work from other cultures –African, Oceania, Native American, and more recently Tibet. I think it is very important to acknowledge where you get your ideas from. Everything comes from somewhere. It all comes from somewhere. One really broad general observation I have now is that people really understand the work and the ideas that are in it. I really appreciate that people get it.

Bending the Grid: Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams is on view at Aljira through March 19, 2016. To inquire about Pat Lay’s limited edition benefit prints call 973.622.1600. Gallery hours are Wednesday – Friday, 12 – 6pm

Saturday, 11am – 4pm.