Morgan, Robert C.; Remarks on Pat Lay’s Technological Metaphors

REMARKS ON PAT LAY’S TECHNOLOGICAL METAPHORS

Robert C. Morgan, 2010

Sideshow Gallery, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, NY

Technology is an ambiguous term, not only in reference to its current social and global applications, but also in the practice of art. This does not mean that art should be removed from an activist involvement. In recent years — depending on the work one chooses to think about — it has become rather difficult to separate these concerns. Some artists will take a critical or ironic position in relation to digital forms and processes, while others may choose to discover the virtue of working in relation to their transformative aesthetic potential. The recent works of Pat Lay are looking in two directions: She engages in the aesthetic potential of digital media. This is for certain. At the same time, she projects social concerns – often on a quiet level, beneath the surface of a first encounter. Her works implicitly offer both a testimony and a critique as a challenge to the cynic. Her collaged digital images (2008-10) imply that technology is a medium in which artists are free to work and to transform into a catalyst for beauty and empowerment. In observing Lay’s recent works on paper, I am inclined to reflect on the Thankas, or Tibetan Buddhist scrolls used in meditation. At the same time, her sculpture elicits a more incisive, confrontational, and activist point of view.

In Transhuman Personae #3 (2005), Lay pays homage to The Spirit of our Times (1919), an early assemblage by Berlin Dadaist, Raoul Hausmann. In contrast to the generic industrial male prototype envisioned by Hausmann, Lay’s sculpture represents a neofuturist feminine beauty. The clay head has been fired, glazed and painted, with various polychrome wires and computer parts inserted into the forehead, the nose, the left frontal lobe, the ears, and various other parts of the head. It is shown on a high pedestal. While the Dadaist head appears a year after the Great War (as it was then called), Lay’s contemporary metaphor shows a more buoyant, optimistic vision of the cybernetic future in which wiring and electrical paraphernalia function as a positive, more ornamental alteration of the body. In an obtuse way, these attributes tend to adorn rather than subtract from the heroic presence of this interracial iconic feminine icon. Much the same could be said of a later permutation, titled Transhuman Personae #11 (2010). While it confronts the spectator with an intensified expressionist variation on a theme, the fired clay head reveals an exorbitant mass of electrical cable and wire. Instead of appearing on a high pedestal, the head is mounted on a camera tripod as if to suggest a mechanized theme resembling traditional tribal masks subjected to cargo cults from Zimbabwe or New Guinea.

Lay has given considerable attention to her collaged digital images over the past couple of years. In that her intention is to represent up-to-date aspects of “man and technology,” these printed works are designed by repeating sections from motherboard patterns. In everyday use, these constitute the system of internal wiring within a computer that activates terminals in the exchange of electronic signals. In BA-E-VO-A #6, images taken from these internal wiring devices have been collaged into a grid format. The digital images, printed in blue, orange, and yellow inks, have been assembled on archival museum board into a symmetrical design. A spherical shape resembling an astronomical star chart appears just above center within the yellow field. Another work from this series, SFL 40 VO #17 may suggest a red Persian carpet, also symmetrical and based on the motherboard pattern. One may discern a tendency to read these collages in terms of a quasi-mystical guide to consciousness taken from the hidden chambers within a computer. In that this technology is temporary — at least, for the present –it is difficult to know exactly where the design of communication technologies will take us in the future. Will they become bio-implants within the body or forms of external atomization? As the architect/writer Witold Rybczynski has made clear: “Any attempt to control technology must take into account not only its mechanical nature, but its human nature as well.” It is, perhaps, this human nature that Pat Lay is attempting to bring into the foreground of our visual sensibility, whether in her deeply insightful systemic collage prints or her intellectually confounding mutant sculptures. They tend to complement one another as two aspects of the technologies we are all trying to comprehend. (2010)

Watkins, Eileen; Exhibition features N.J. artists, The Star Ledger, August 18

EXHIBITION FEATURES N.J. ARTISTS

By Eileen Watkins

Originally published in The Star-Ledger

Newark, NJ

August 18, 1996

Raynor, Vivien; Fresh-Looking Work From Six Veterans With a Wealth of Experience, The New York Times, August 11, 1996

FOR all the youthful implications of its title, ''Six Artists: The 1990's,'' at the State Museum here, is a show about maturity. The work, three-quarters of it produced in the last two years, is certainly new. The artists -- Emma Amos, Bill Barrell, John Goodyear, Gary Kuehn, Patricia Lay and George Segal -- are anything but, Mr. Segal being the eldest, at 72, and Ms. Lay the youngest, at 55. Besides, all are well known in the state, and most have seen the limelight in Manhattan, in particular Mr. Segal, who has been a fixture in the Sidney Janis stable since 1967 in addition to starring at numerous museums, domestic and foreign.

They may appear as new because artists, like wine, need to set awhile. But credit must also go to the organizers of the show: Zoltan Buki, the museum's curator of fine art, and Alison Weld, its assistant curator of contemporary New Jersey arts.

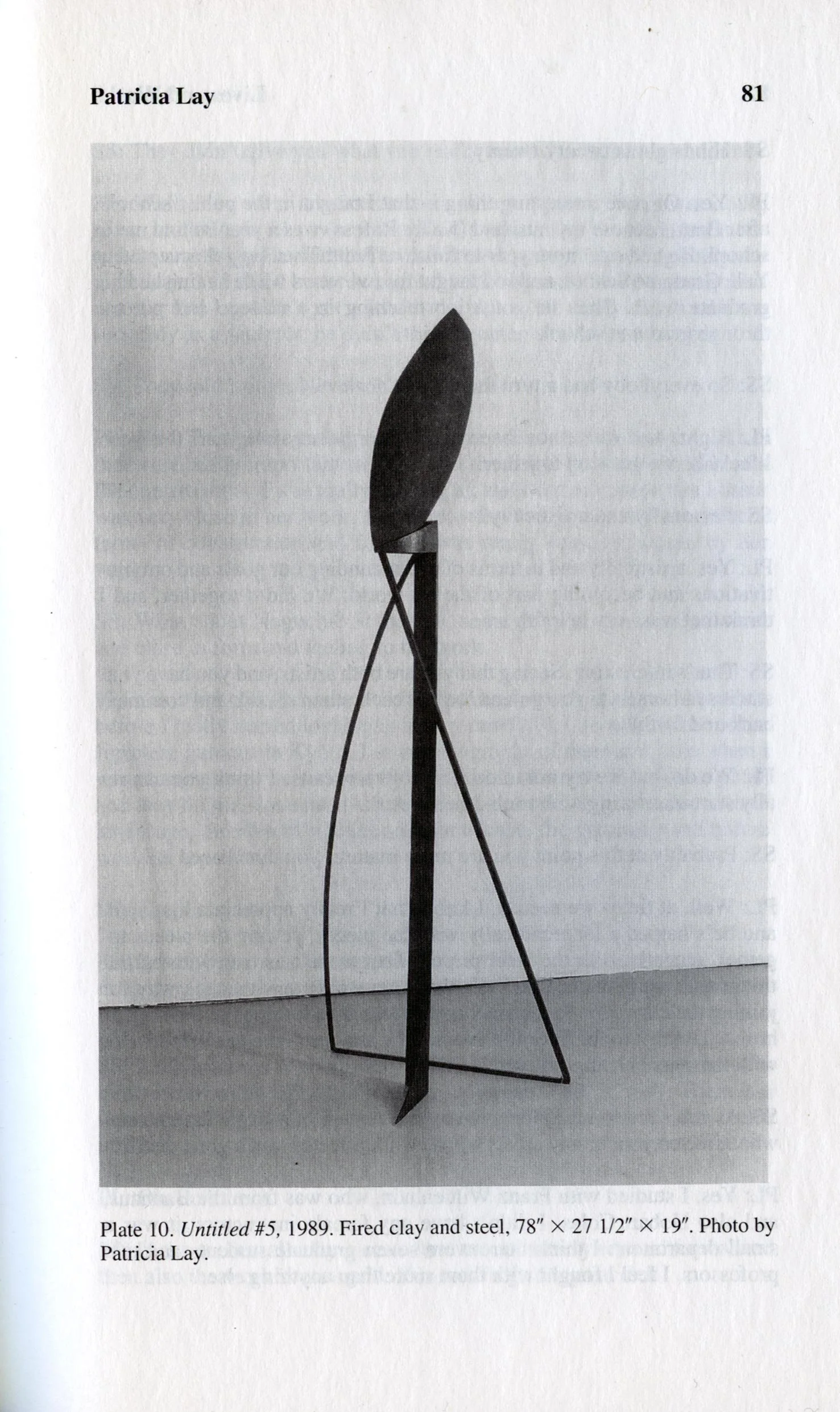

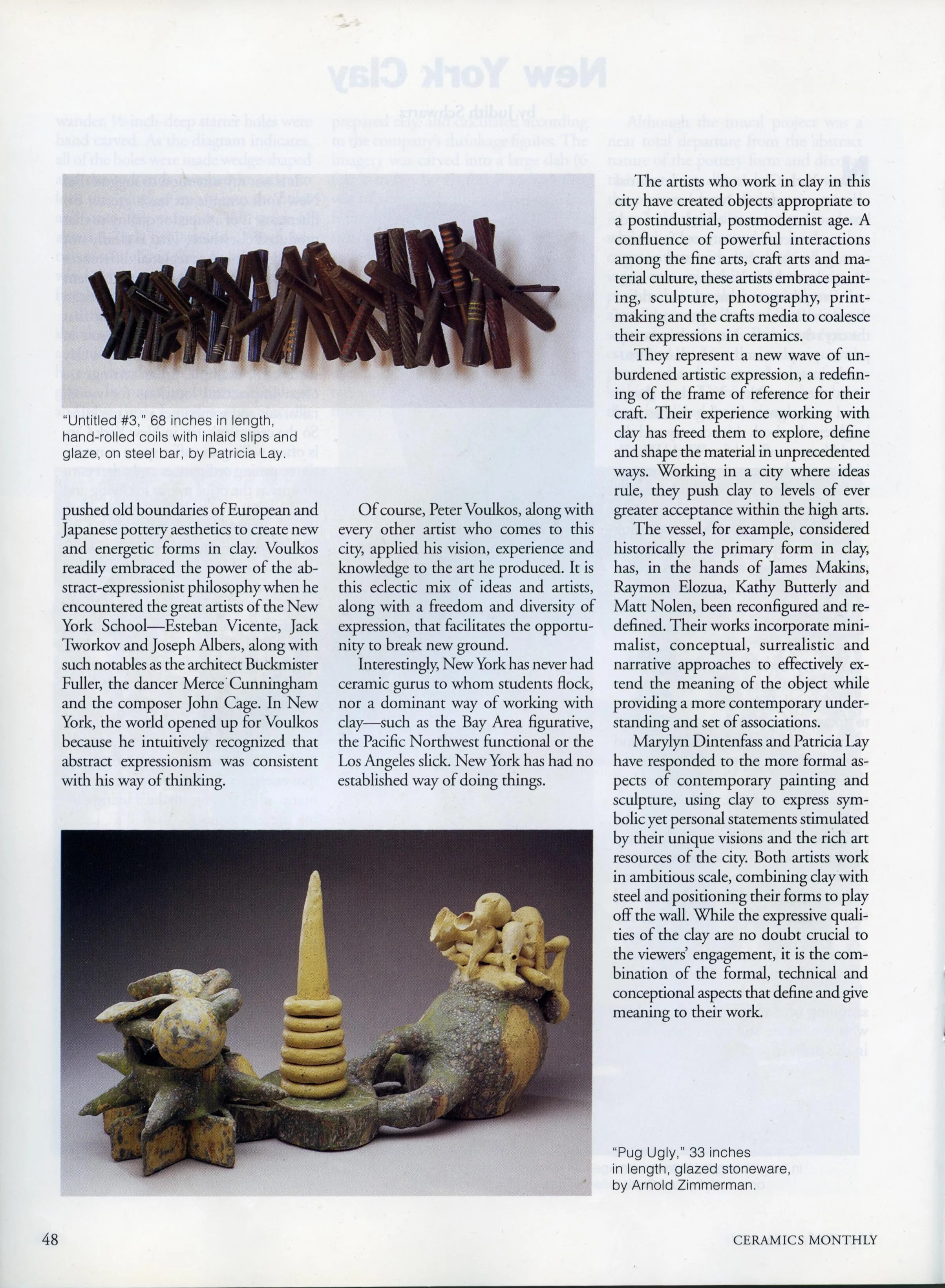

Patricia Lay has long steered a course between art and craft, working in the materials of both but generally tending toward craft in her results. Here, she again combines materials, specifically fired clay and steel rods, but the outcome is monumental in ways that suggest Brancusi and Tony Smith at his most Systemic. The clay is black, but in the case of the bagel shapes threaded on a vertical pole, it comes incised with orange stripes. Other vertical shish kebabs are packed with black shapes resembling vertebrae, while the rods hung on the walls horizontally are strung with geometrical and organic shapes, spaced far apart. As usual, there are intimations of African art, but a label indicates that Ms. Lay's repetitions refer to the tedium of women's work, presumably as opposed to those practiced by the young Sol LeWitt and the old Brancusi.

Emma Amos does not share Ms. Lay's duality, but she alludes to her own past as a weaver by adding collage African fabrics to her paintings; she also incorporates photographs and reproductions. But above all, the artist is concerned with her own life and those of her fellow African-Americans. Hence, a typical Amos work is so filled with personal and socio-political allusions that it requires a key. One overpowering example is the canvas that is half a painting of a seated woman resembling Whoopi Goldberg, attired in pants suit and red boots, and half a scrambled image of Billie Holiday in action. To judge from the artist's caption, buried in this is an allusion to her mother, who made gloves, notably for the singer Hazel Scott, and who loved Holiday more than any man in her life. Her daughter conveys the same intensity in her art.

GARY KUEHN contributes, on the one hand, rectangles of pink, yellow and green paint applied to three panes of plexiglass and incised edge to edge with scribbles and scratches, and, on the other hand, a sequence of three sculptures in wood coated with graphite, all suggesting a torso cut off at the thighs. This begins with a tree trunk forked at top and bottom, continues with a similar form made by joining tree limbs together, and ends with a geometric version assembled out of beams. It is up to the viewer to decide if the shapes represent progress or regress.

John Goodyear is a Minimalist with leanings toward the kinetic, a social conscience and a sense of humor -- an unlikely combination if ever there was one. His canvases, however, are small, square and, in a prim way, rather pretty, especially when the slats of painted wood that screen them like Venetian blinds swing back and forth, casting shadows. Each merits close attention, but none more than ''Chimpanzee Power'' and ''Capital Gains for the Rich.'' The one features a simian silhouette composed of small black squares on a background of yellow; the other is a white canvas filled with golden-brown arabesques undulating like the permed hair styles of the 1930's.

Compared with Mr. Goodyear's installation, Bill Barrell's is a burst of automatism, but one that refers to the world and keeps the same beat, which seems to have accelerated in recent years. Although the images are more easily osmosed than analyzed, most are amalgams of heads, figures, objects, houses and hints of landscape that somehow add up to interiors. Recurring elements like the striped ribbon pique curiosity, but it is not necessary to identify the parts to appreciate the whole. In any event, viewers have their hands full taking in the fauvish color, the range of texture and an attack as vigorous as the late George McNeil's.

Last but not least are the grisaille still lifes representing the sculptor George Segal's return to painting in the early 1990's -- an about-face that appears to have been emotional as well as esthetic. Some images evoke French Realism of the 19th century; others suggest the Cubist Picasso. All are extraordinarily somber in atmosphere. Mr. Segal could be the one artist registering the pulse of the time.

SIX ARTISTS: THE 1990's

New Jersey State Museum

205 West State Street, Trenton

Through Sept. 8. Hours: Tuesdays through Saturdays, 9 A.M. to 4:45 P.M.; Sundays, noon to 5 P.M.

Cotter, Holland; New Jersey Shares Worldly Treasures, The New York Times, July 12, 1996

Excerpt from New York Times Article:

THIS is a fairly low-key summer in New Jersey art museums, with one really spectacular exhibition unfortunately ending its run this weekend in Newark.

New Jersey State Museum

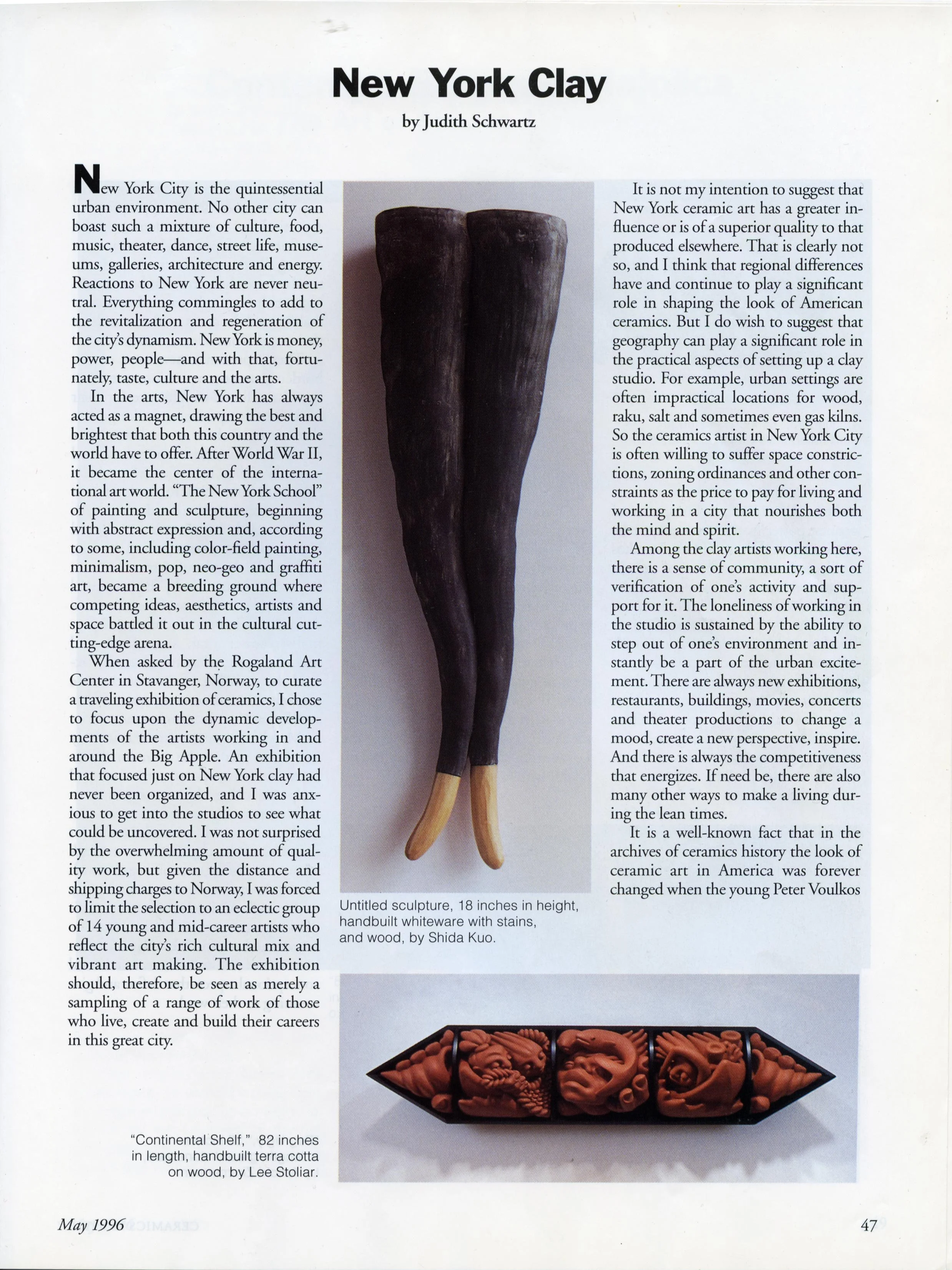

"Six Artists: The 1990's," organized by Zoltan Buki and Alison Weld, holds center stage at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton. Most of the participants have Manhattan reputations but have been brought together here on a different geographic pretext: they either live or work in New Jersey. (Three teach at Rutgers University.)

George Segal is the best-known figure, though he is represented here by thick-textured, lugubrious grisaille paintings of still lifes rather than his signature sculptures. If nothing else, they underscore the fact that this artist's work has always been closer to Expressionism than to the Pop art with which he is often linked.

Emma Amos and Bill Barrell also fall somewhere in the Expressionist camp, Mr. Barrell with brushy, chromatically bright semi-abstractions, Ms. Amos with a racially charged figurative subject hemmed in by borders stitched from African cloth.

Judging by their quirky, pointed titles ("Laptops for the Poor," "Prayer in Schools"), John Goodyear's paintings also have political subtexts, though they're a little hard to decipher. What catches the attention is their odd format. The diagrammatic images are half-obscured by wooden screens suspended an inch or so from the painting's surfaces, some of which gently sway from side to side.

Like Ms. Amos's work, Patricia Lay's sculpture combines materials (metal and ceramic) associated with both art and craft. She works incrementally in small forms and, whether piled up in thin columns or lined up horizontally on the wall, they keep up a consistently engaging conversation. The show's most striking works, though, are the quietest: tree-trunk sculptures by Gary Kuehn entirely covered with the sheen of pencil graphite, bringing nature and culture into a thought-provoking alliance.

No visitor will want to miss the museum's small but solid permanent collection of work by black artists. It begins in the 19th century with a portrait of a child by Joshua Johnson and landscapes by Robert Duncanson and Edward Mitchell Bannister, then blossoms into real diversity closer to our own time.

The abstract painting by Alma Thomas titled "Wind Tossing Late Autumn Leaves" (1976) is a beauty, with its shower of black curved lines on a white ground. So, in its different way, is Sister Gertrude Morgan's undated "Revelation," with its red-haired angels hoisting megaphone-shaped trumpets and its Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse dressed like cowboys. The collection is brought up to date with strong pieces by Benny Andrews, Mel Edwards, Richard Hunt and Alison Saar.

Skouen, Tina; Arbeiderbladet, Oslo, Norway; July 19

NYTT SKUDD I SKULPTURPARKEN (NEW SHOT IN THE SCULPTURE PARK)

By Tina Skouen

Originally published in Norwegian newspaper Arbeiderbladet

July 19, 1996

Raynor, Vivien; Some of the Best Works Turn Out to Be Three-Dimensional, The New York Times, April 18, 1993

Excerpt from New York Times Article:

Mr. Barrell is best known as a painter with a reputation that goes back to the 1960's. Recently, however, he has become something of an eminence grise in the scene that is developing in this neighborhood, and that is to some extent the doing of the Lorillard's owners. They not only rent studios to artists but also make available to them a space for exhibitions, the better to attract new tenants.

Presumably, the symbiosis will last only as long as it takes to fill this block-sized relic of the machine age. But that could be a while, and in the meantime the artists are taking full advantage of the situation, forming and re-forming groups under various titles and staging exhibitions.

"The Source," produced by Artomic Age, has several participants in common with its predecessors and, like most large anthologies -- especially those with more than one curator -- it is diverse to the point of lumpiness. Then again, it is different for including several artists from Germany and, perhaps more significant, veterans like Mr. Barrell.

One of these is Jay Milder with "The Runner," a figure in cast aluminum that resembles de Kooning's Expressionist "Clam Digger" bronzes except that the modeling is less self-indulgent and more specific. Though little more than a slab with a profile and an upraised hand, this piece, scarcely two feet tall, has a presence out of all proportion to its size.

Dominick Capobianco, also known as a painter, is represented by something that could be read as a comment on George Segal and his myriad followers. It is a pair of terra-cotta feet cast from life that repose on a mat empty, as if they were shucked-off snakeskins.

Another very effective work is Patricia Lay's six rods rammed into a white wall. Impaled on or attached to each of them are disks or lozenges of clay, from one to six per rod and all painted black. The whole production, which is easily twanged, suggests target practice by spear throwers.

Come to think of it, the most successful works are all in three dimensions. Among them are Nancy Cohen's wall assemblage, which is a pod made of white paper over wire and combined with a curving stick; Karin Luner's feminist take on the term "source," which is two Perrier bottles fixed to pour one into the other except that the water level in both remains unchanged, and the dead-pan comment by Roger Sayre on the art of tearing the lids of coffee containers. which is seven such lids each centered on a white ground and framed in wood.

For Al Preciado, commonplace materials, in this case the wires coated in colored plastic that telephone repairmen customarily leave in their wake, are but a beginning. The artist twists the wires into figures, wraps them in aluminum "armor" and deploys them and their improvised rifles on earth girdled by ramparts of wood. Less Mannerist in their spindliness and an inch or two shorter, these warriors could be the "Little People" for whom Charles Simonds used to erect terra-cotta dwellings on vacant lots in Manhattan.

Elvira Nungesser's banner of dark gray that is crisscrossed with painted white lines and recalls the drawings of Liubov Popova hangs from the ceiling, while her sculpture of galvanized metal sheeting, folded, origami style, crouches on the floor below.

For her monuments to the Ninja Turtles, Ana Golici erects a tower of four black boxes, furnishing each with a plastic turtle and a reproduction of a work by the artist for which it is named. Having nominated herself as an honorary turtle, the artist adds a fifth box, containing a soft turtle toy with symbolic breasts added and an enlarged photograph of a flea. Looks like a career move to this observer.

Alison Weld contributes a combination of painting and assemblage that could be a comment on East versus West. Though never exactly tranquil, the horizontals and verticals of Ms. Weld's abstract imagery have become almost violent, being now slathered on in waxy-looking pigment of all colors and vigorously scored. The effect is of an old wall giving up its layers of paint. Beside the canvas hangs a floor-to-ceiling scroll of white paper weighed down with a stone and a single wand of pampas grass.

Richards Ruben's "Asking," a panel scumbled all over in blues except for flashes of yellow-orange at the corners, looks like a haven. Yet, with its undulating edges, the image turns out to be every bit as unsettling as Ms. Weld's, what with the panel's wary edges and vermilion stretcher left visible on one side.

Though the show could stand pruning, the good points definitely outweigh the bad, which, by the way, include a curious reluctance to list names alphabetically -- in the catalogue or anywhere else. Hours are 2 to 5 P.M. Friday through Sunday.

Raynor, Vivien; A Show by 40 Women Who Teach Art, The New York Times, March 15, 1992

FOR its "New Jersey Project Invitational," the Robeson Center Gallery, at Rutgers University here, has mustered 40 female artists. One might say "only" 40, for it has long been apparent that the majority of artists exhibiting in New Jersey are women.

Credit for this and the corresponding increases in the number of women in curatorial positions and on art faculties must go to the feminist movement. In art, however, this began 20 years ago when artists like Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago, together with such writers as Linda Nochlin and Lucy Lippard, declared war on male supremacy.

In her catalogue essay, Judith Brodsky, director of the Center for Innovative Printmaking at Rutgers and one of the Robeson exhibitors, tells the story of those heady times, emphasizing the formation of the Women's Caucus for Art and the development of a feminist art theory. But the proof of the pudding is in the show, whose participants are all teachers.

To a casual observer, the situation in Manhattan might appear less rosy. The Guerilla Girls are no longer pasting the city with posters that came close to asking if you had hugged a female artist today; a spot check of the magazines Art in America and Artnews indicates that the ratio of men to women reviewed is about 3 to 1. Professor Brodsky says that progress has been made but that men still have the edge where sales, prices and inclusion in museum collections are concerned.

If that is the case, now may be the time to reconsider questions of quality, but the organizers of the project seem more interested in quantity. Officially, the display is meant "to encourage women and girls throughout the state to view themselves as potential creators of art." This is not especially good news for those who, troubled by the present surplus of artists and dwindling subsidies, would prefer that the encouragement were directed at good work.

But politics will be politics, and the project is financed by the State Department of Higher Education, and has been since 1986. Who can question the idea of integrating "gender" into the curriculums of public and private colleges?

Anyway, one hopes that in future shows more attention will be paid to appearances. This one is overcrowded and seems parked rather than installed, and because of the congestion and lack of choreography, the spectacle seems, at first glance, to be no more than a roundup of generic art.

Janet Taylor Pickett acted as curator, but "with much reluctance," she says in the catalogue statement. And no wonder. The job would be impossible in a space twice the size.

Nevertheless, a few works manage to assert themselves. Van Gogh may have had the last word on irises, but Aundreta Wright injects pizazz into the show with a vivid drawing of the flowers. As reticent as this is bold, Susy Baudoin Suarez's oil on paper appears to be an abstraction, but it evokes shacks along a waterfront and exudes tranquillity.

A painter who studied with Kokoschka, Anneke Prins Simons fills a small canvas with angular but soft-edged forms in red, orange, black and white, heightened by touches of Prussian blue. This skillfully painted abstraction is urban in atmosphere, and its mood one of controlled anger.

Though euphoric in her essay, Professor Brodsky takes a somewhat ironic view of women's progress in an oil pastel combined with collage and titled "The Goddesses Weep." The Greek deities line the top of the canvas; a figure resembling the Princess of Wales is repeated 18 times along the bottom.

In between are renditions of news photographs, notably three of Hedda Nussbaum, and below them, a translation of Titian's "Venus of Urbino" and other, less easily identified "pinups."

Edith Feisner's Cubist abstraction catches the eye with its 16 squares divided into shaded quarters, the more so for being in the medium of cross-stitch and beautifully executed. Both of Judith Fleischer's effective assemblages involve strips and squares of paper that are white on top and colored underneath and are stuffed into slots cut into white boards.

Ms. Pickett contributes an assemblage composed of black and blue boards, arcs cut from tin cans, a photograph of a woman with face obscured by beads, the whole thing garnished with carpet tacks, nails and a crest of feathers.

E .A. Racette is represented by a host of inscrutable shapes cast in different colored bronzes and deployed on a black surface under a sheet of Plexiglas. Patricia Lay holds the floor with three tall steel rods on which are impaled, shish kebab-style, small forms modeled in dark clay.

As a manifestation of the feminist "academy," the invitational is impressive; as an art exhibition, it serves only to make the visitor think of the Robeson's "golden age" in the 1980's, when Alison Weld reigned as curator. (The gallery is without a curator now.)

The show closes March 20. The gallery is at 350 Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. Hours are 11:30 A.M. to 5 P.M. Monday, Thursday and Friday and 11:30 A.M. to 6 P.M. Tuesday and Wednesday.

Watkins, Eileen; Star-Ledger, October 18

By Eileen Watkins

Originally published in The Star-Ledger

Newark, NJ

October 18, 1991