Berecz, Agnes; PAT LAY: MULTIDIMENSIONAL, catalog essay, April 2024

Elza Kayal Gallery

New York, NY

March 15 - April 2024

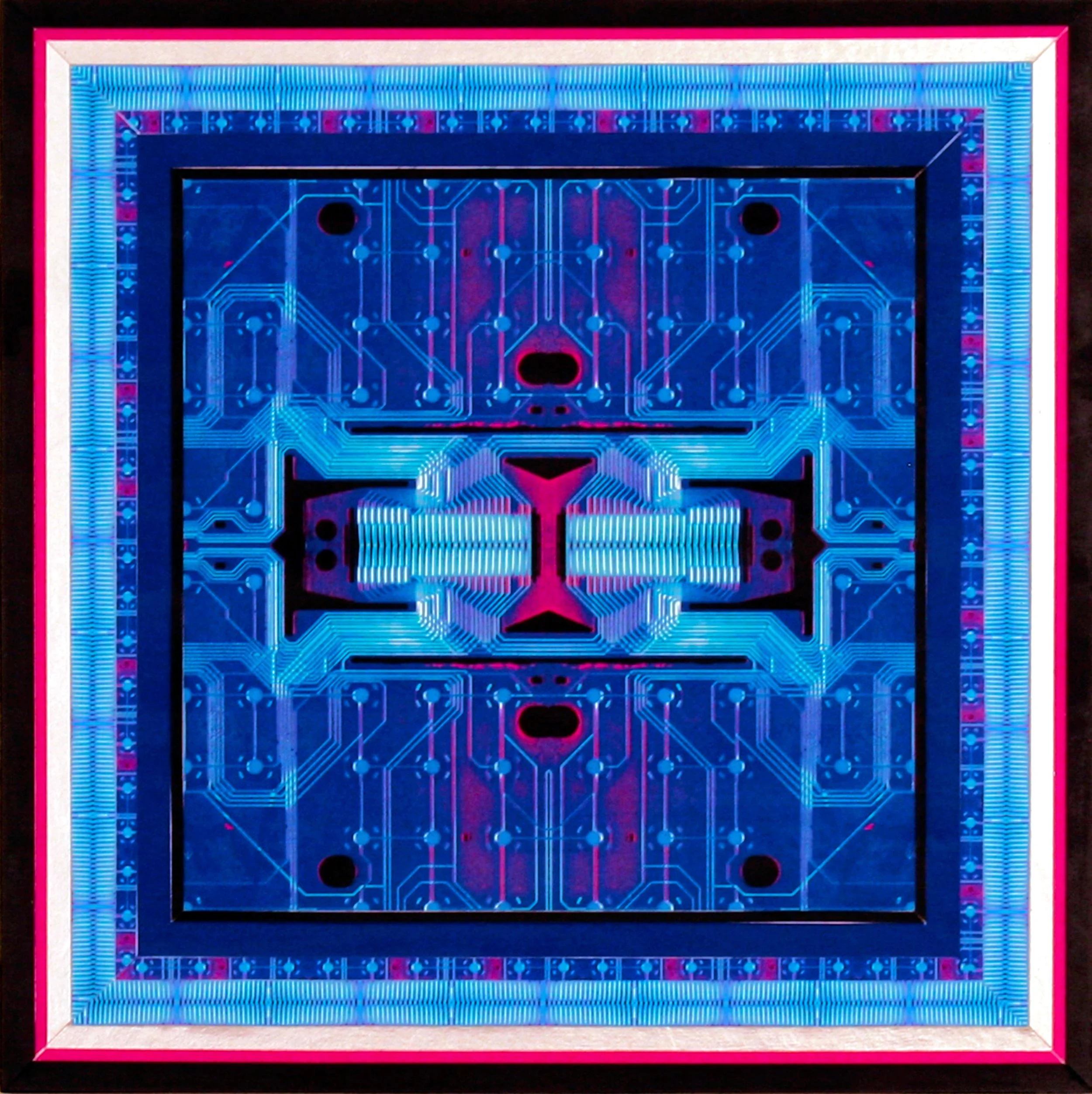

If dimensions are means of measure that orient and order things and beings, Pat Lay’s work, a practice in many formats and media addressing various histories and cultures, is indeed multidimensional.

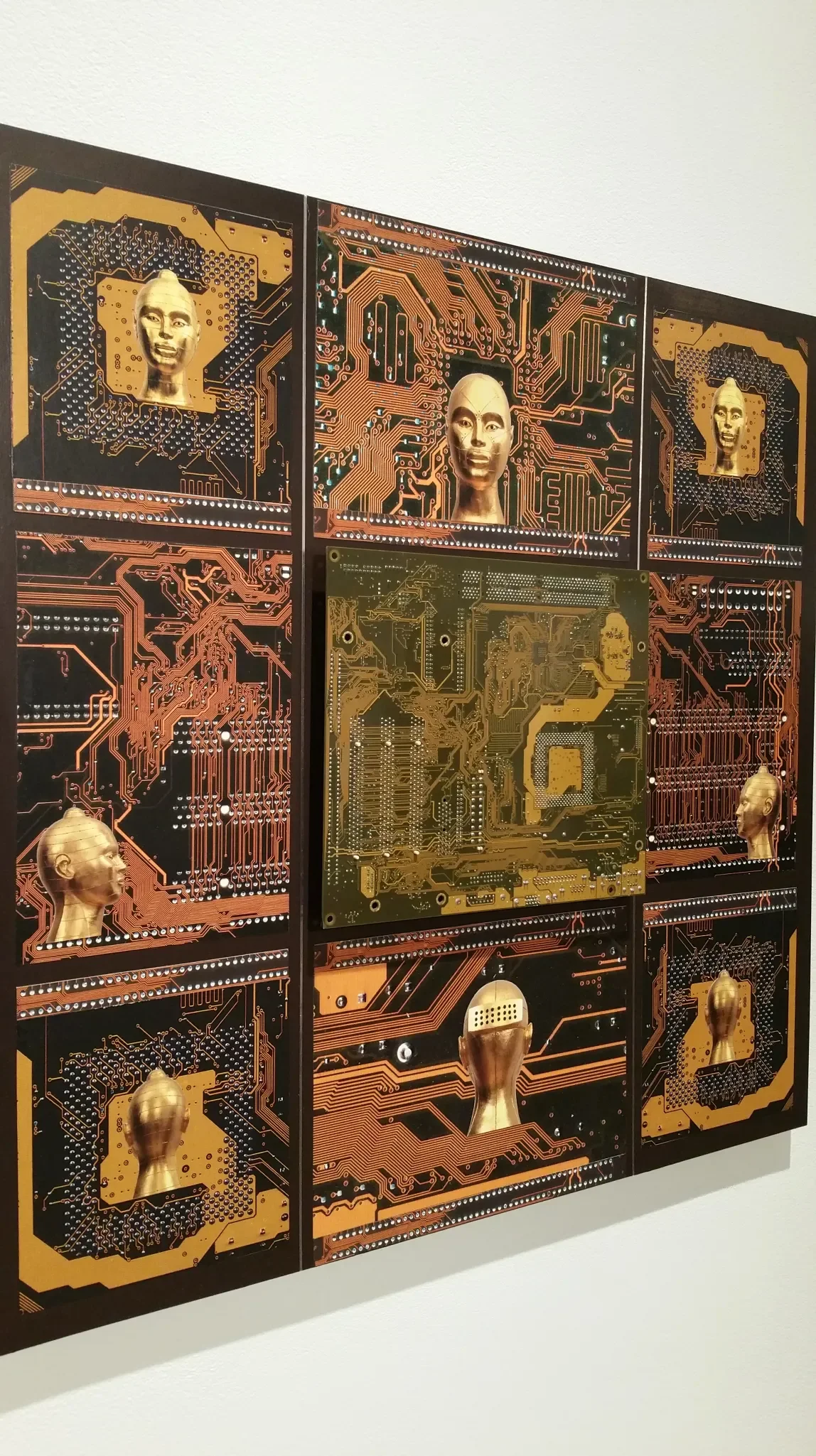

Working since the late 1960s, Lay became an artist in the technological society of the second machine age where clear-cut distinctions between body and machine, organic and computational, human and robot have been probed and increasingly destabilized. Deeply engaged with the generative effect of technology on the material conditions and modes of human life, Lay creates sculptures, scrolls, collages and prints by using images and objects from the realm of technology as raw materials and motifs to reimagine the world we share with machines.

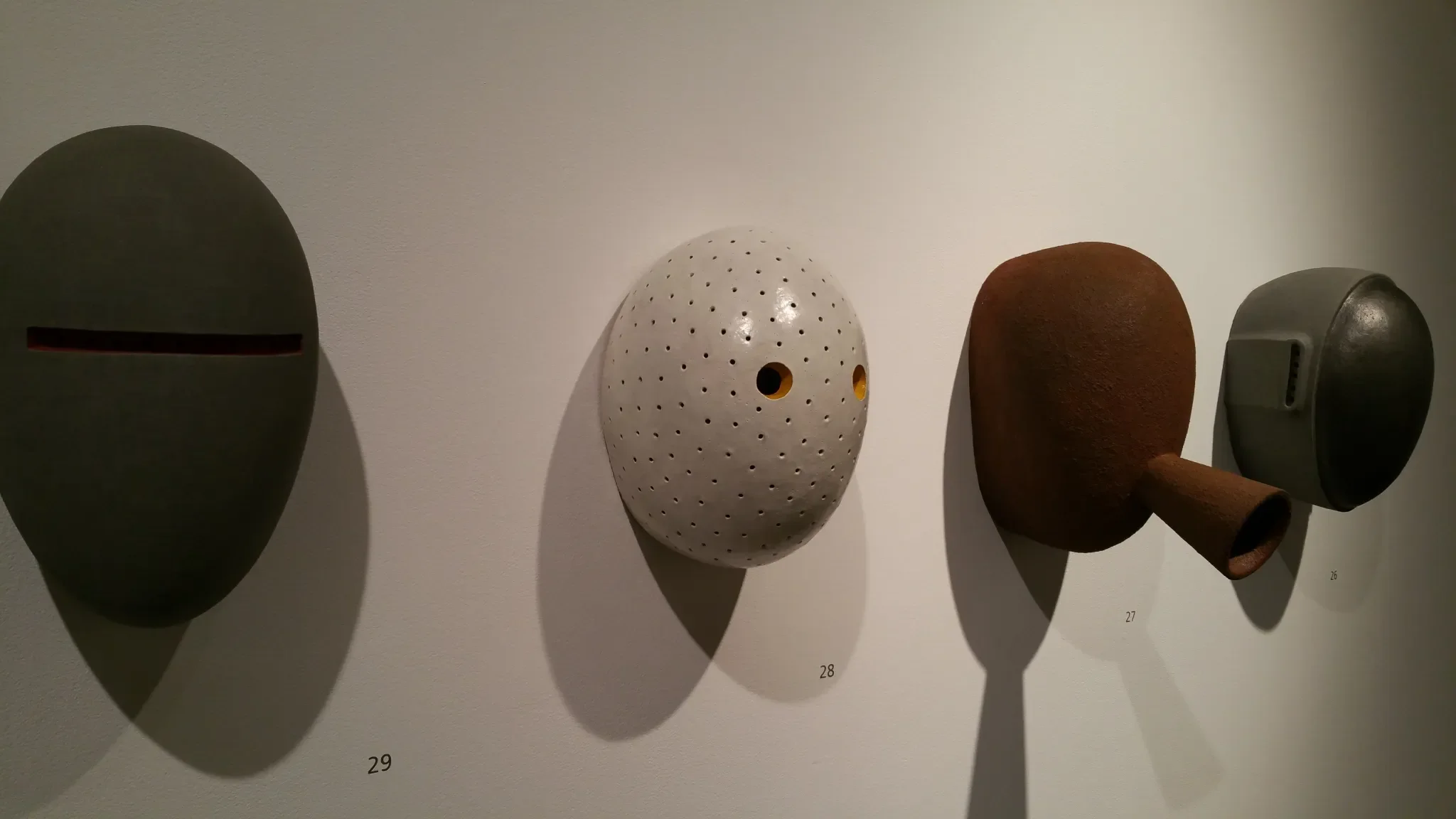

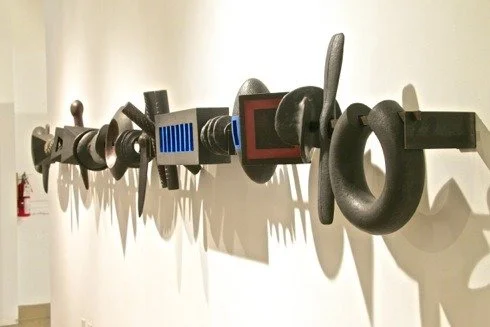

In her recent sculpture-series, Soul Bot and Nested Bot, she juxtaposes computer parts such as aluminum heat sinks and cooler fans with vividly colored, fired clay objects whose distorted geometric volumes bear bodily connotations. Amalgams of industrial fragments and hand-made vessels, Soul Bots are part bodies and part objects. By uniting the commercially fabricated, metal computer parts that imply gyrating motion with the stillness of the often amusingly erotic clay bodies, Lay animates and reclaims the object world of contemporary technology.

Trained as a sculptor and working with clay for decades, Lay’s organic robots in the Soul Bot and Nest Bot series also bring into play the historically laden relationship of pedestal and sculpture. In addition to using shelves as well as low and high pedestals to display her sculptures either alone, in pairs or as multipart units, recently Lay also began using collapsed, disordered clay grids, or as she calls them ‘nests,’ to contain and elevate her three-dimensional work. In the 2023 installation, titled Urban Birds, she placed the vaguely ornithological clay vessels on a grid of glazed ceramic tiles. A multipart sculpture situated as an elevated floor piece, Urban Birds indicates a return to the artist’s 1970s floor-based architectural landscapes.

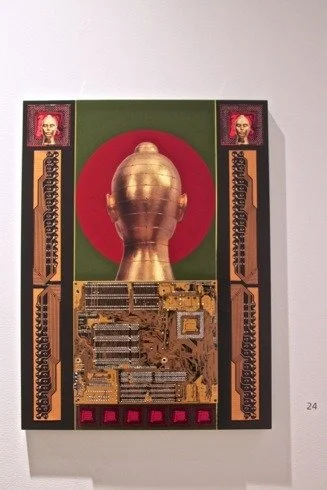

In another instance of circularity, Lay employs the machine parts and the sensual clay bodies of her sculptures as images in Botscapes, a series of digital collages that suggest fragmented, visionary landscapes. Collage has been a primary device in Lay’s practice since the early 2000s when, after working with multipart structures and assemblages and inspired by the kaleidoscopic composition of Tibetan mandalas, she created her first digital collages. Ten years later, she started working on her large-scale, digital and painted collages adopting the vertical scroll format.

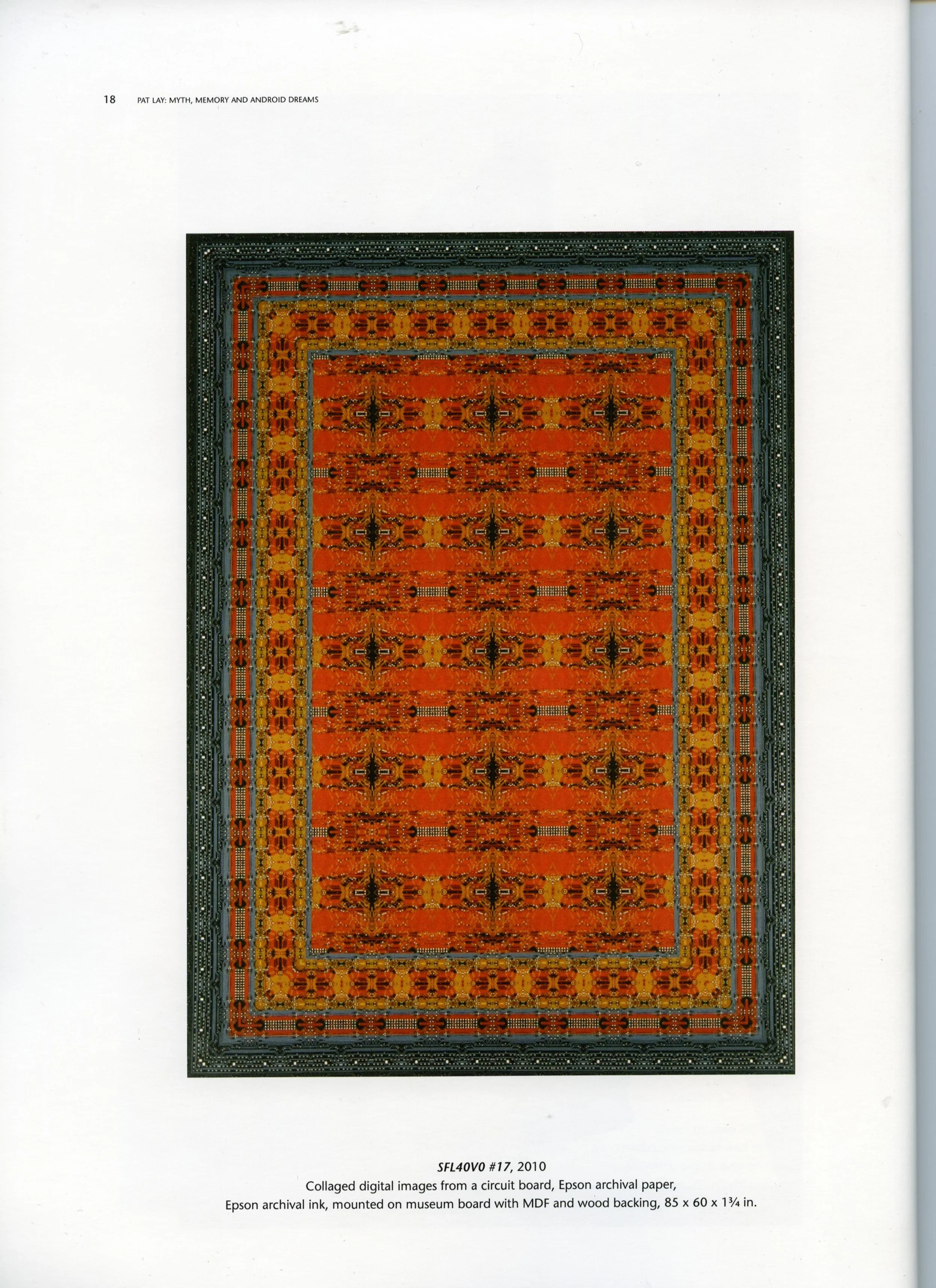

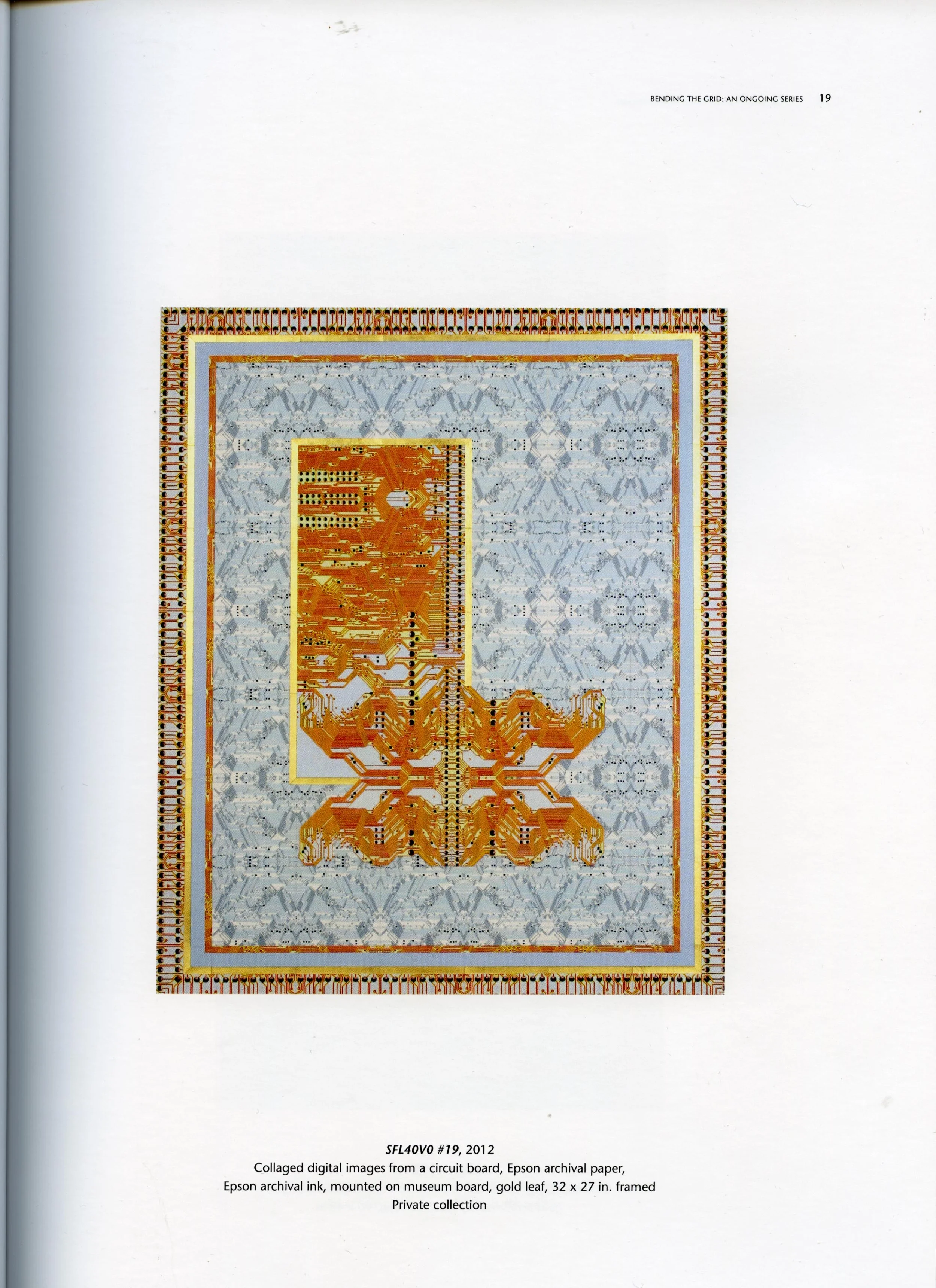

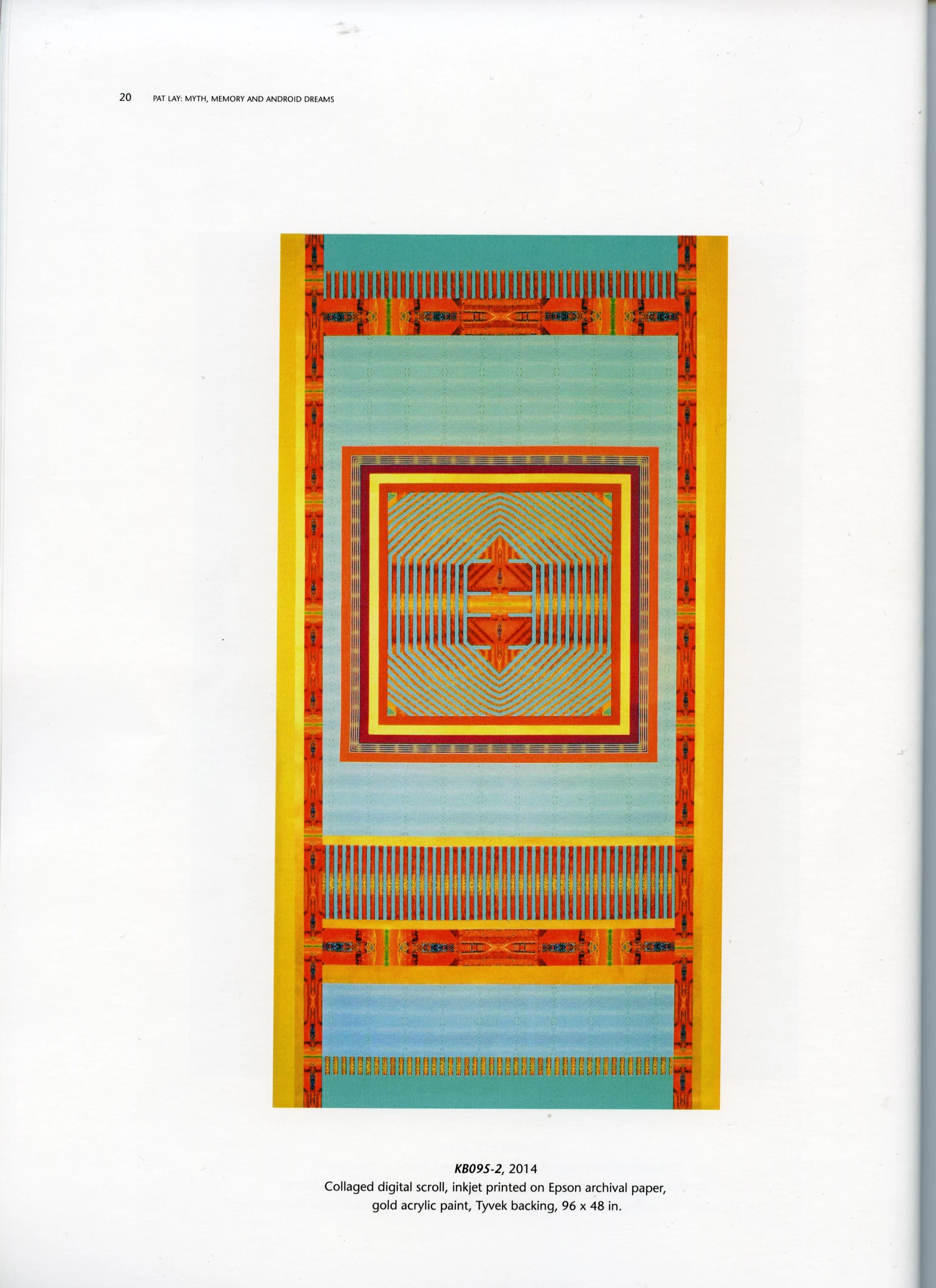

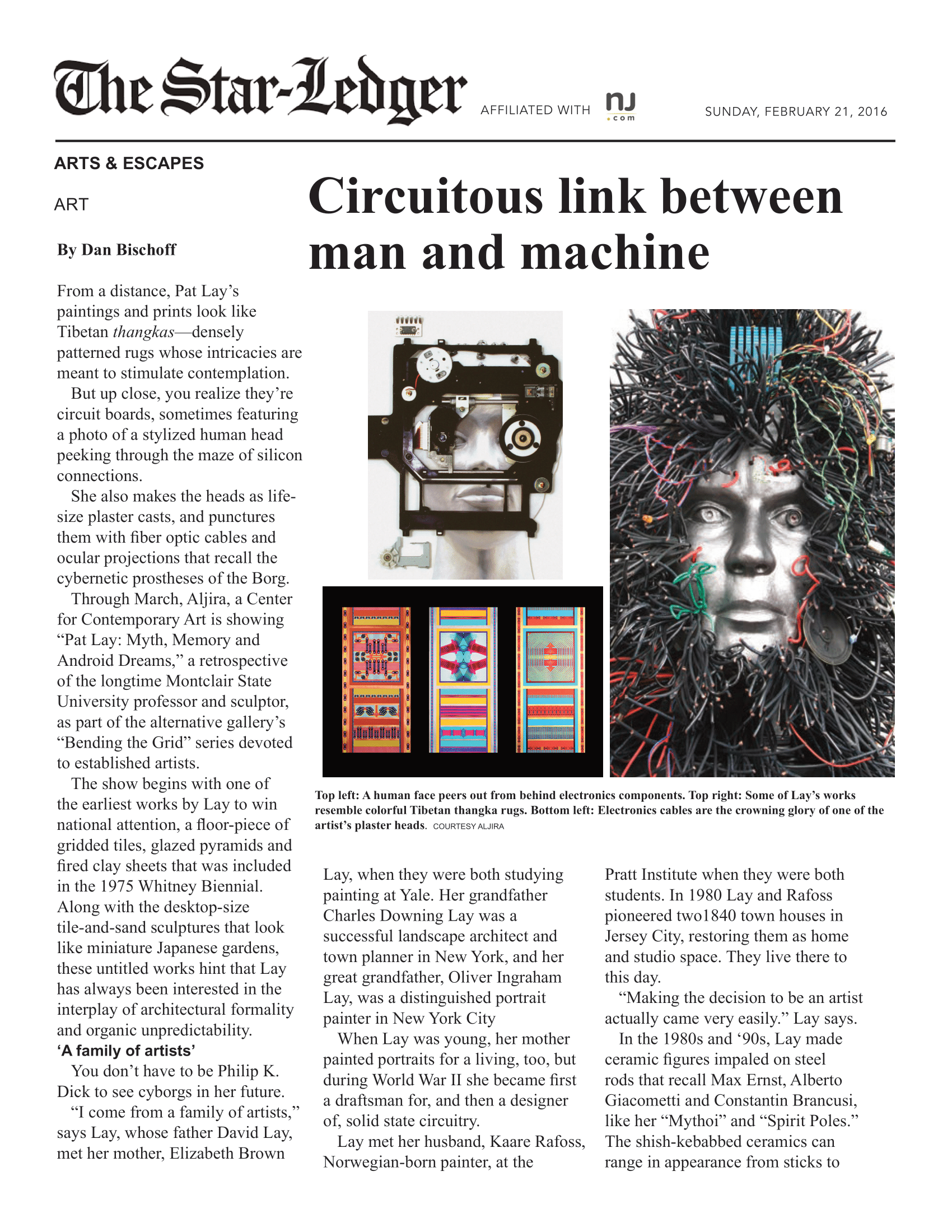

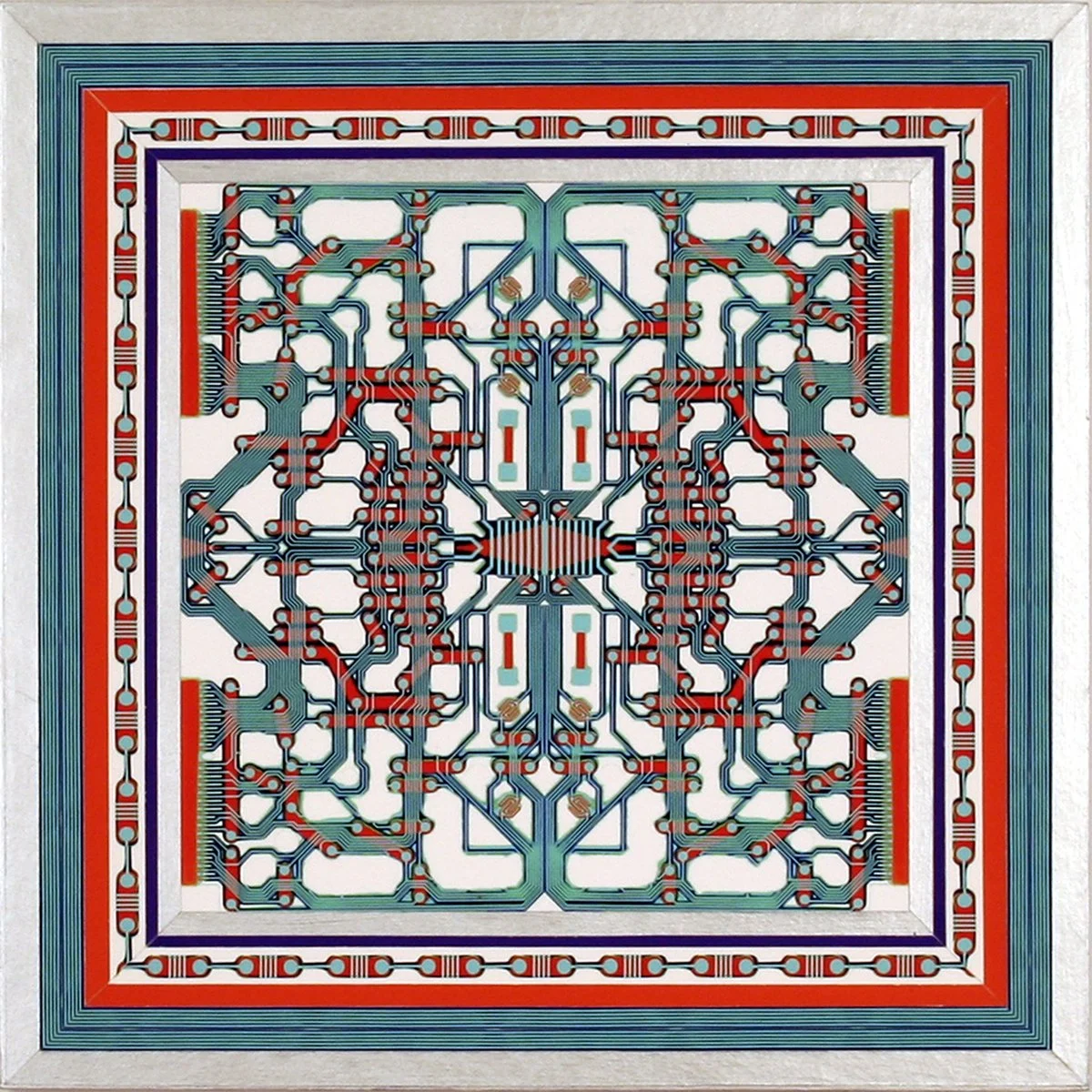

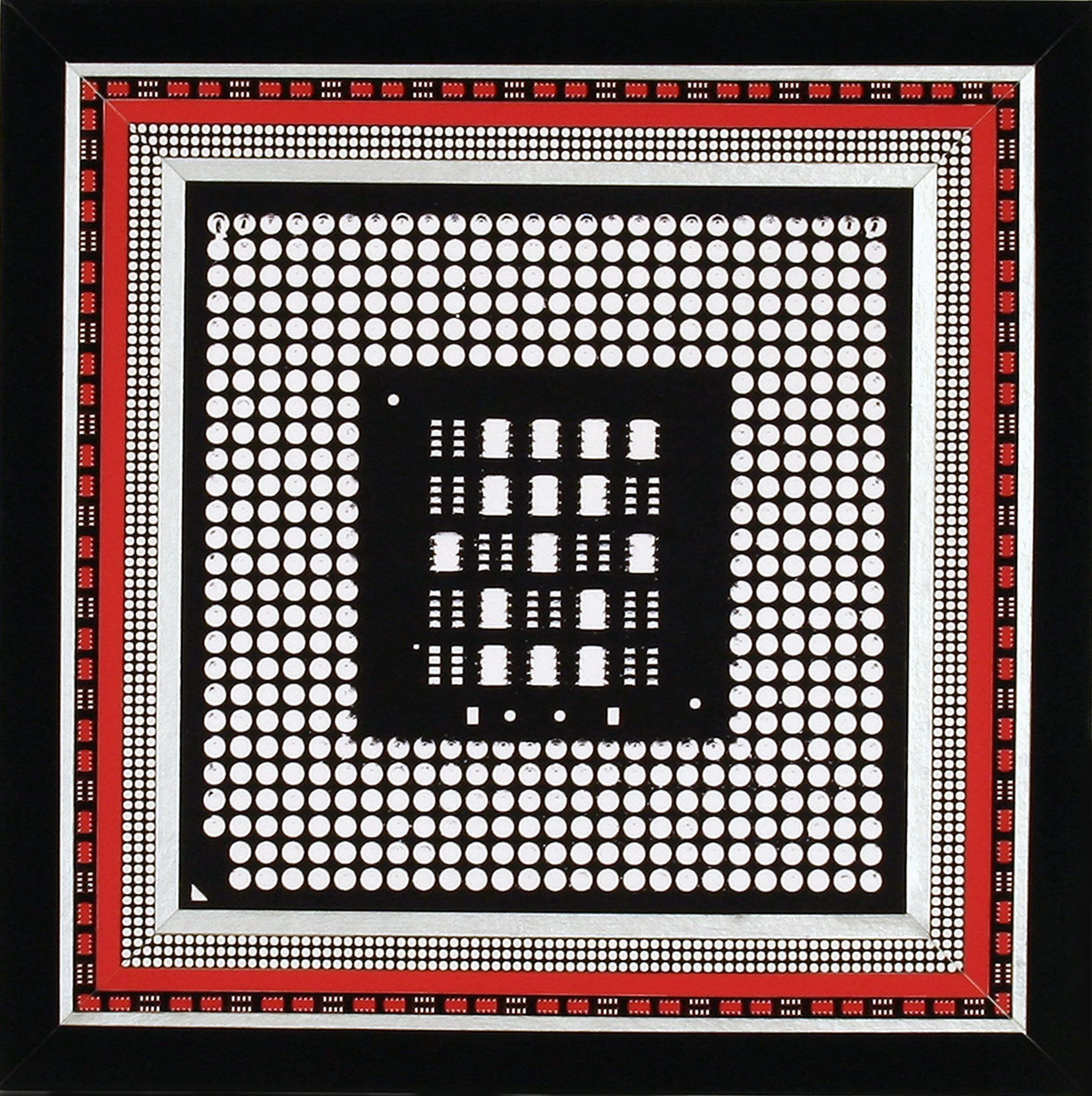

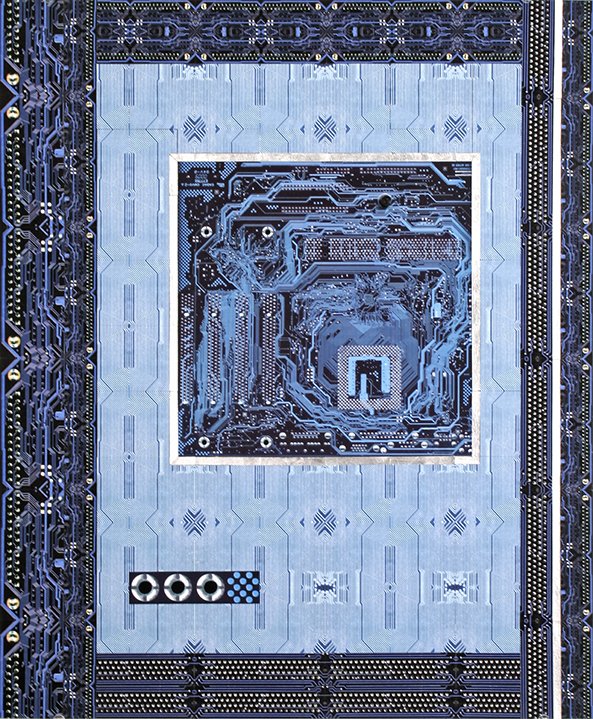

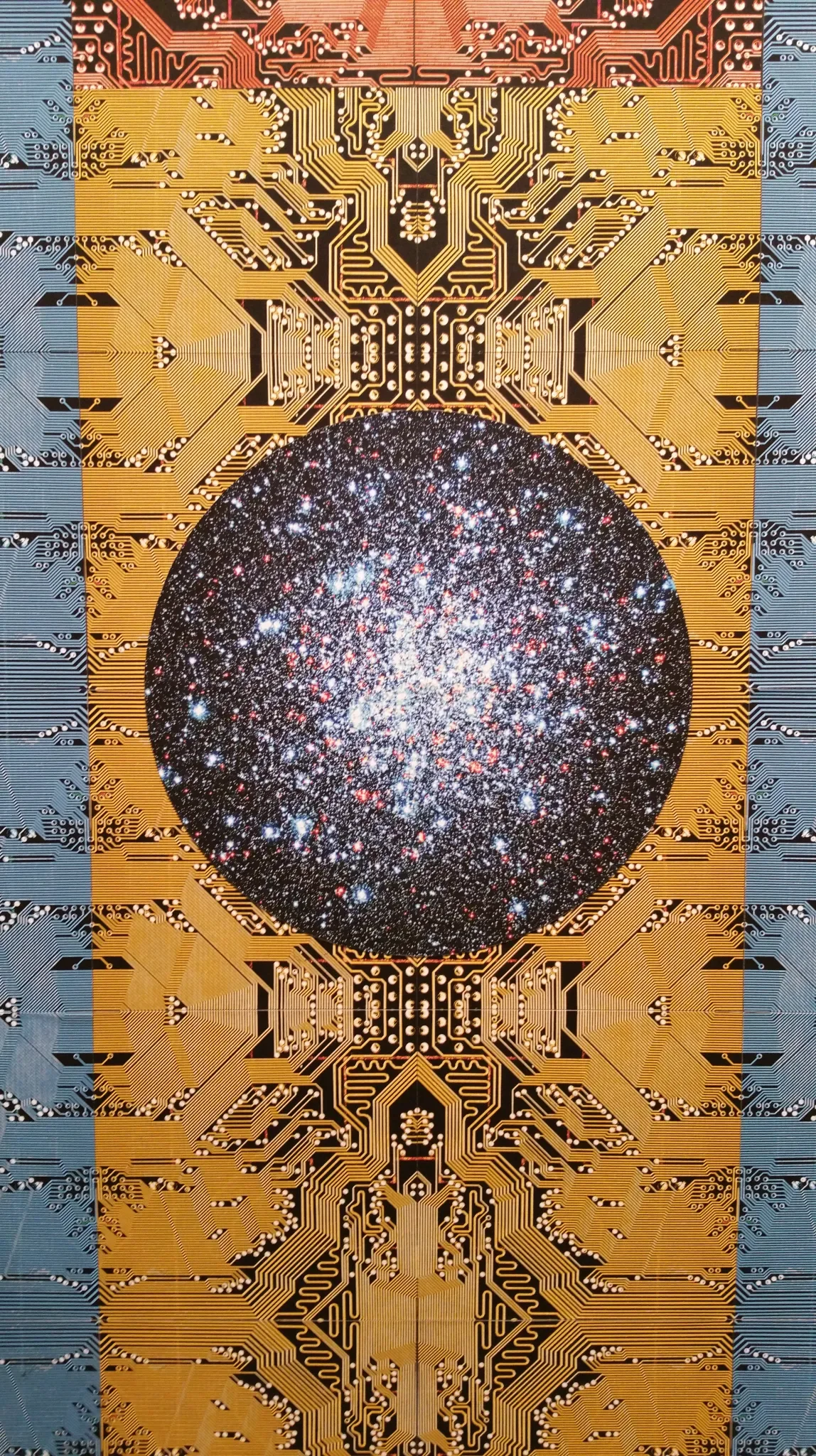

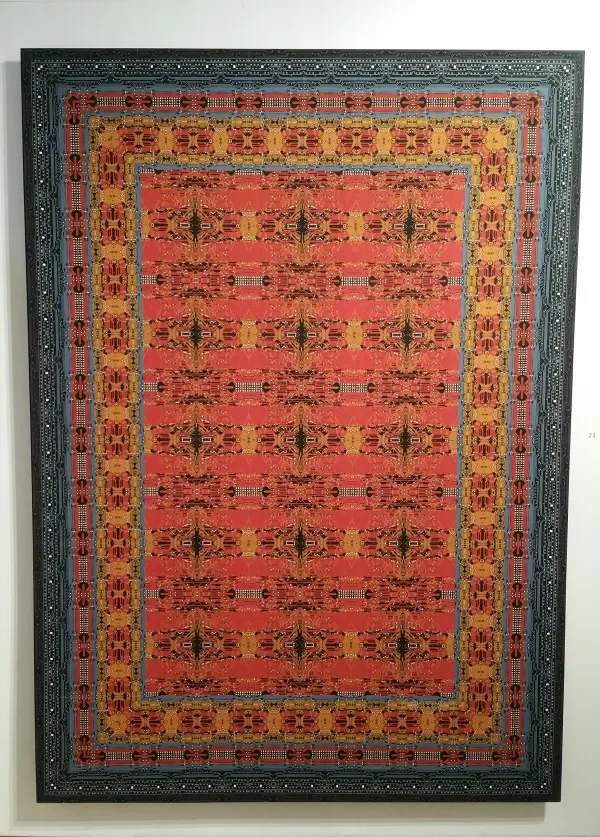

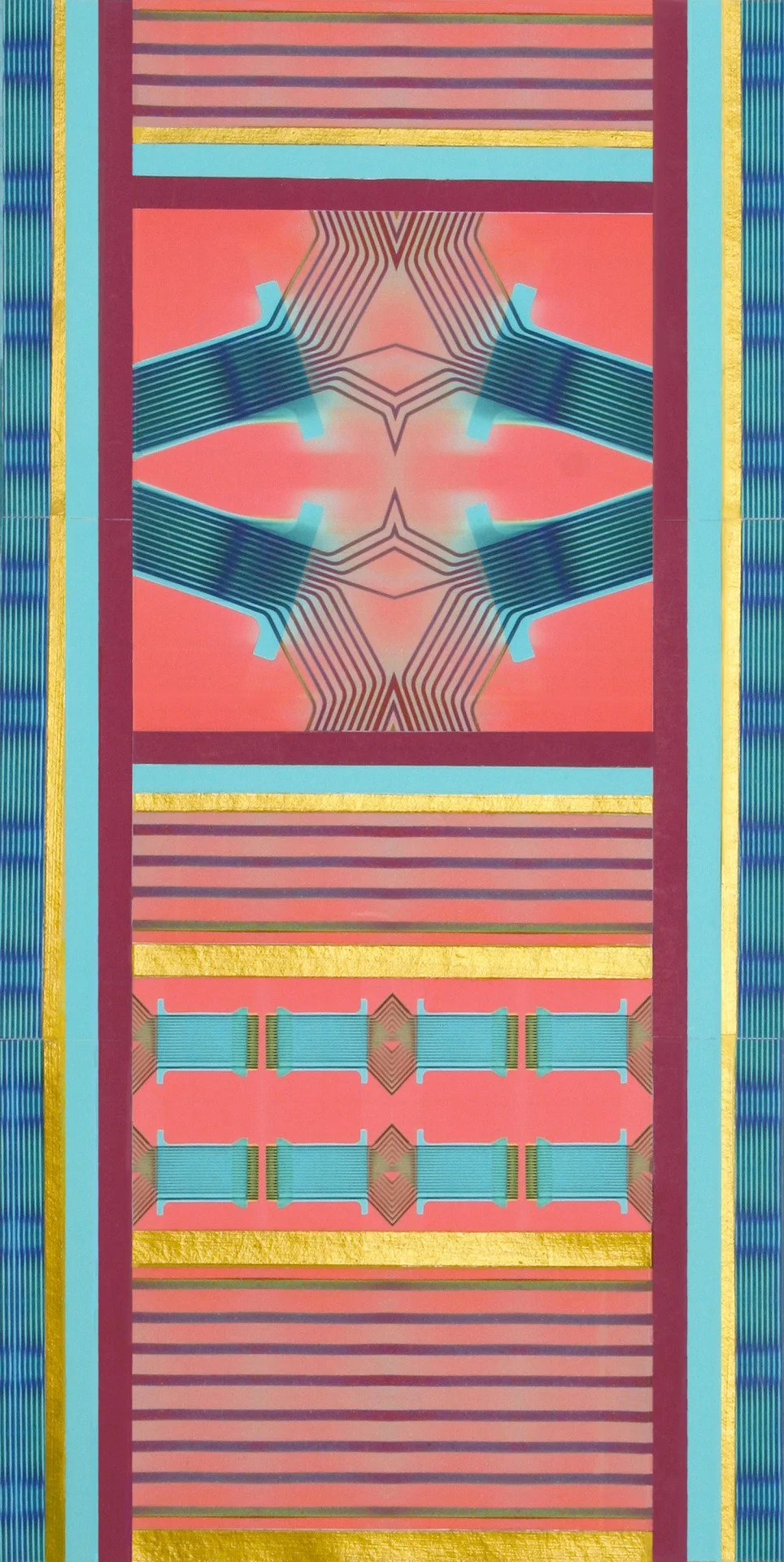

Constructed from digital photographs and the enlarged and altered images of computer motherboards, the meticulously composed and both formally and metaphorically layered scrolls feature numerical codes and details of electronic circuits in repetitive, ornamental structures. Reminiscent of the spiritual devices of Himalayan cultures, the painted and collaged scrolls replace pictures of Buddhist deities and narratives with abstract patterns of techno-scientific imagery. In Extreme Deep Field (2014) the artist framed the Hubble telescope’s iconic image of galaxies that are billions of years away from us with diagrammatic patterns of enlarged circuit boards fusing the infinitesimal and the interstellar as well as space and surface.

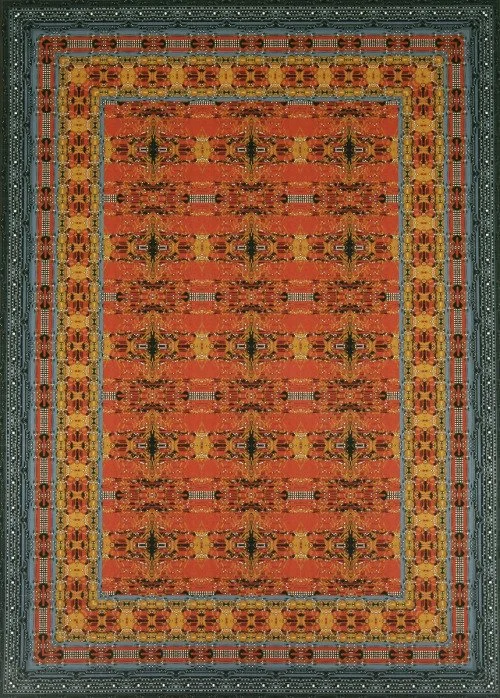

Like telescopes, Lay’s scrolls and prints are also time machines. Historically aware and diverse in its references, her work brings into play cultural artifacts, scientific inquiries, and spiritual practices across time and space. Her scrolls and prints evoke a matrix of allusions ranging from navigational devices such as maps and charts to decorative objects and spiritual tool like Persian carpets, Tibetan thangkas, and Byzantine mosaics, while they also expand on emblematic methods and strategies of modern and contemporary Western art, including collage, assemblage, and the grid.

As the artist stated, “meditating on the past, present, and future, my scrolls question and critique our paradoxical relationship and obsession with technology and what it now means to be human.”[1] Lay’s multidimensional work operates in a carefully negotiated space between artistic practices, cultures, and geographic territories. A critical commentary about machines as both necessary tools and substitute deities, she proposes new, hybrid taxonomies that address the technologically mediated human experience where souls and bots, motherboards and pictures of the cosmos coexist.

Ágnes Berecz

(PhD University of Paris I, Pantheon-Sorbonne) is an art historian and a critic. The author of the monograph, Simon Hantai (2013), and 100 Years, 100 Artworks: A History of Modern and Contemporary Art (2019), Berecz teaches contemporary art at Pratt Institute and lectures at the Museum of Modern Art.

[1] Etty Yaniv, “Pat Lay: Mapping New Interiors,” Art Spiel (March 18, 2019) https://artspiel.org/pat-lay-mapping-new-interiors/

Sims, Patterson; An Interview With Patricia Lay, in catalog Myth, Memory and Android Dreams

AN INTERVIEW WITH PATRICIA LAY (2016)

By Patterson Sims, Independent Art Curator, Writer and Consultant

Originally published in Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams

Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art, Newark New Jersey

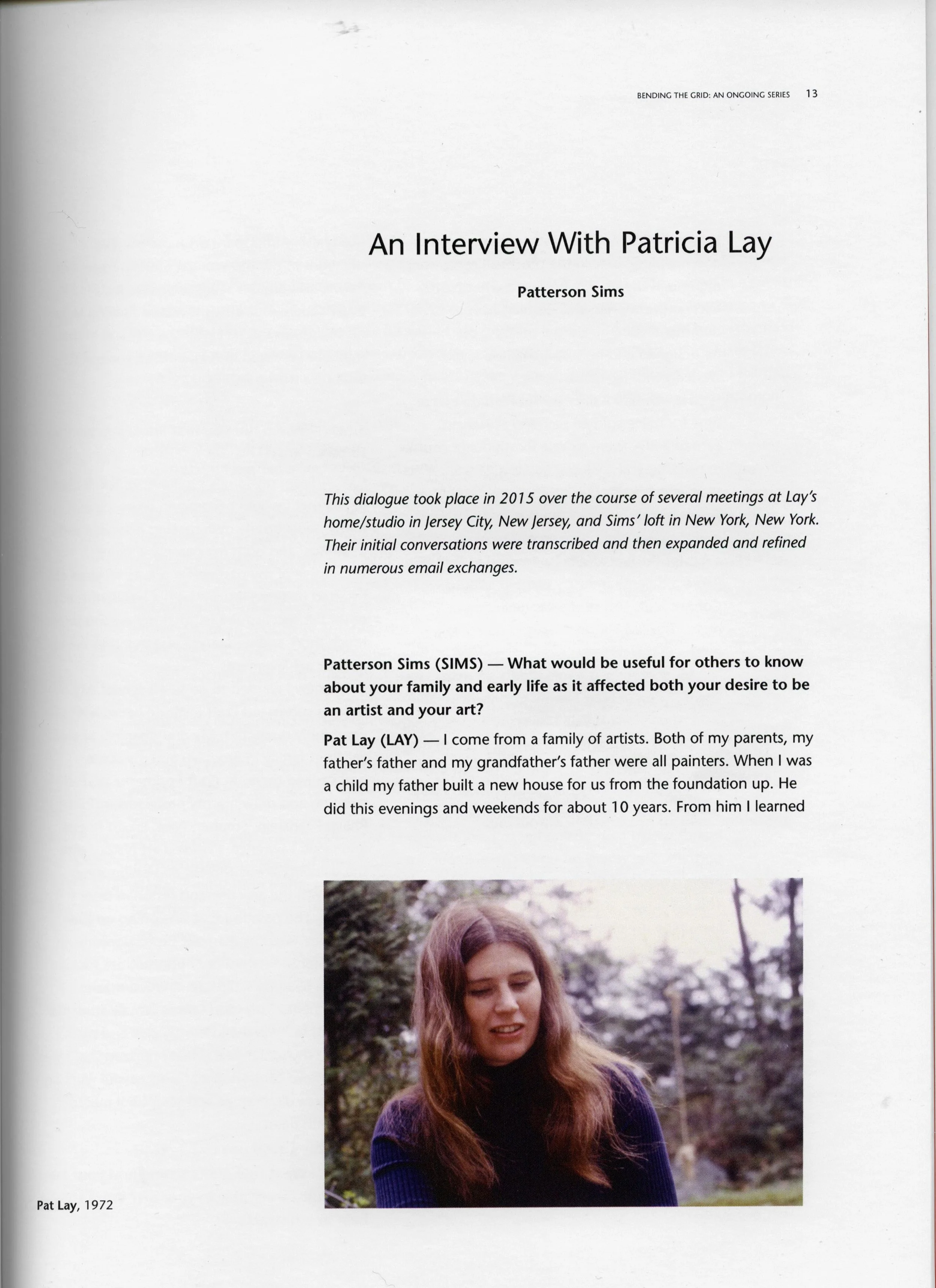

This dialogue took place in 2015 over the course of several meetings at Lay’s home/studio in Jersey City, New Jersey, and Sims’ loft in New York, New York. Their initial conversations were transcribed and then expanded and refined in numerous email exchanges.

SIMS: What would be useful for others to know about your family and early life as it impacted on your wanting to be an artist and you art?

LAY: I come from a family of artists. Both of my parents, my father’s father, and my grandfather’s father were all painters. When I was a child my father built a new house for us from the foundations up. He did this evenings and weekends for about ten years. From him I learned how to build things. He would let my brother and me participate in the process.

I remember digging in the mud, wheeling a wheelbarrow filled with concrete, and learning how to use a hammer. Before he started building our house he designed and built sailboats. He loved working with his hands. He was also a painter, but he didn’t have time for it. He studied painting at Harvard, earned a BFA, went to Yale for graduate courses in painting, and took classes at the Art Students League in NYC. Then my brother and I were born. During World War II he had the choice of going to war or working at a job for the war effort. He worked at Remington Rand, a defense industry plant in Milford, Connecticut and studied engineering at night. This led him to a life-long career as a production engineer.

My mother was a role model on many levels. She grew up in New Haven, Connecticut and studied painting at Yale University and received her BFA in 1936. After my parents married they moved to New York City and continued their study at the Art students League. When I was still very young in Connecticut my mother’s friends would commission her to paint their portraits. She would set up her easel in our living room, and they would come for sittings. This continued until I was in third grade. When I was nine my mother worked as a draftswomen for an electronics company, later she became a designer of solid-state circuits. I remember her showing me drawings with layers and layers of tracing paper with lines connecting the dots. They were plans for electronic circuitry. Recently a friend suggested that my mother ‘s rendering may have sparked my present interest in circuit boards.

The summer of 1962, between my junior and senior years at Pratt, my mother and I took a nine-week road trip to thirteen European countries. We drove from city to city visiting nearly every important art museum. The highlight of the trip was the Spoleto Festival in Italy. David Smith’s sculptures were installed in every square of the city. It was so thrilling to see his sculptures interact with the city and at this moment I realized that I identified more with sculpture than painting.

SIMS: When did you first know you wanted to be an artist?

LAY: From my family’s influences, it was clear to me that I would become an artist. I spent many hours on my own making drawings and paintings, and both my parents were very supportive of my passion for art. At ten years old I started painting lessons with a local artist, but I never felt successful. I felt that my parents were much more talented, and I was trying to live up to their achievements.

I knew I wanted to go to art school. My parents suggested Pratt Institute because it was highly respected. My grandparents knew the Pratt family in Brooklyn and my uncle had studied there. At Pratt I primarily studied painting and drawing, my professors included Phillip Pearlstein, Stephen Pace, Ernest Briggs, and Jacob Lawrence. I studied art history with the painter George McNeil and philosophy of art with the art critic and historian Dore Ashton. The painting that was going on then was dominated by Abstract Expressionism. Pratt offered very limited opportunities for women to study sculpture. It was a macho department. They didn’t allow female students to weld, so I worked in mostly clay and plaster. I was in my senior year when I realized that I was much more comfortable and successful working with three-dimensions and sculptural materials than with paint.

SIMS: What role did teaching and your later academic career play in your art? Was it help or a distraction?

LAY: Early on I realized that making art was not a secure way to make a living, and that I would have to have another profession to have a stable economic life. Teaching on the college level was the obvious choice because it’s not a nine-to-five job. As a teacher you are expected to actively pursue your specialty: art making is built into the job.

I always liked the give-and-take with students, a mutual questioning and conversation. I learned from the students and they learned from me, especially the MFA students. I started teaching at the college level when I was 27. I realized that the students saw me as a role model, and I worked hard at my career as an artist to earn their respect and trust. The academic environment also expanded my knowledge of art history, philosophy, the art world, technology and new processes.

But teaching had its distractions. It was difficult to carry through on a studio project. Many times experiments in new directions were left unresolved. The studio work would be sabotaged by an academic report that needed to be written or a grant that had to be submitted.

SIMS: How did your participation in the 1975 Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial exhibition impact your career as an artist?

LAY: Well, I guess it didn’t, really, though I thought that it would open doors. This particular biennial was large and included many emerging artists, and I was one of them. Marcia Tucker was the specific curator of the five who choose my work. The show got some decidedly negative press, but that is pretty typical for a Whitney Biennial.

SIMS: Did you have a gallery going into the exhibition?

LAY: No, and I did not have a gallery as a result of the show. It may have led to other shows, but it was not instrumental in establishing gallery representation. I was ill prepared to deal with the business of art. It was not something that was discussed at Pratt or graduate school. We were all purists and idealistic and felt that it was the gallery’s responsibility to promote our work.

SIMS: Though the grid, immaculate execution, and formalist abstraction prevail in your art, your work has gone through several phases. How might you highlight its overriding characteristics and issues?

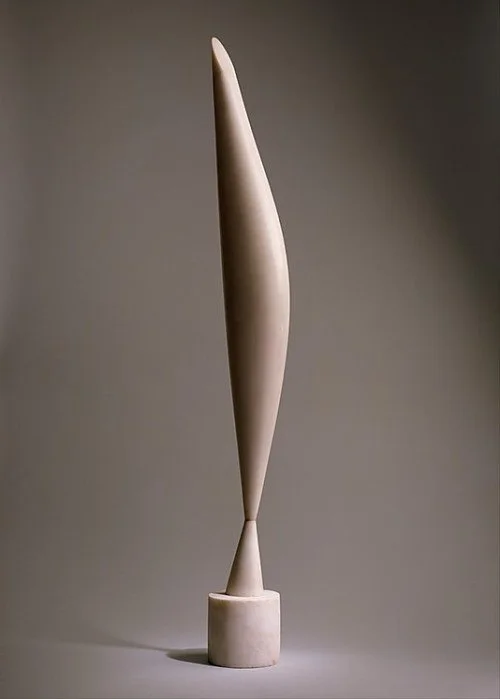

I look to art history for structure and content. In that sense I am a formalist. In the late sixties my fired clay works were geometric, abstract, and concerned with the repetition of form. The Primary Structures show in 1966 at the Jewish Museum was an important influence. In the 1970’s the grid gave to a more open structure. I became interested in the visual discourse between nature and geometry as manifested in the Earth Works movement and formal Japanese Zen gardens. In the 80’s I introduced welded steel in combination with fired clay and incorporated sculptural elements influenced by David Smith and Brancusi. These works were abstract yet suggest a figurative gesture and scale. In the 90’s African and Oceanic art were my primary inspirational sources. Starting in 2000, I combined and hybridized human elements and technology. This work incorporates fired clay, steel, mixed media and ready -made computer parts. In my 2014-15 scroll pieces the structure is formal and incorporates the designs of printed circuit boards. The content, processes, and materials are intrinsically post-modern with the infusion of Persian and Tibetan influences

SIMS: Initiated with that trip you took to Europe with your mother in 1962, you’ve traveled extensively, going in the last twenty years to China, Africa, India, and South America. How have these travels impacted on your work and ways of thinking?

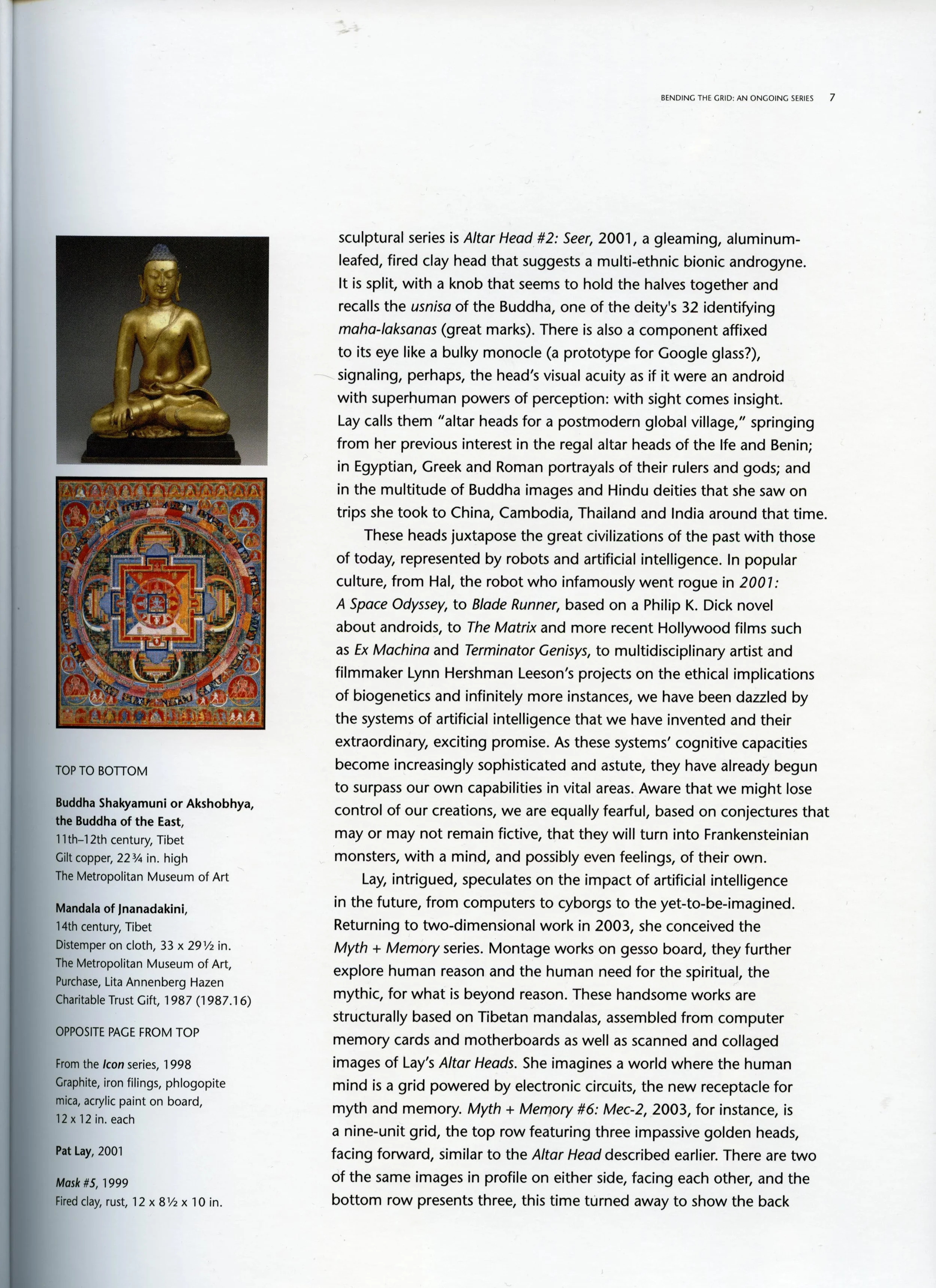

LAY: My European trip with my mother made me realize that to be a good artist it is really important to know the history of art. Now I travel with my daughter. We have focused on visiting Asia, Africa, and South America. We primarily visit museums and historical sights. It is the art, architecture and differences between cultures that influence my work. In Thailand, Cambodia, and India I was struck by the impact and spiritual beauty of Buddha and Hindu deities and in the power emanating from idealized human form. As a result of these trips I started to use the human head as an androgynous, hybrid, post-human form.

Travels to Egypt, Istanbul, Rome, and Peru have added new resource materials to expand my ideas and imagery. The statuary of Pharaonic Egypt, the colors and patterns of the Turkish carpets and tile work, portrait sculptures from ancient Rome, and pre-Columbian clay figures in Peru have had a profound influence on my work.

SIMS: Your travels have clearly opened you to art history and what can be learned in museums. You have not traveled to Tibet, yet Tibetan thangkas have clearly been instrumental to your recent works on paper and larger wall works.

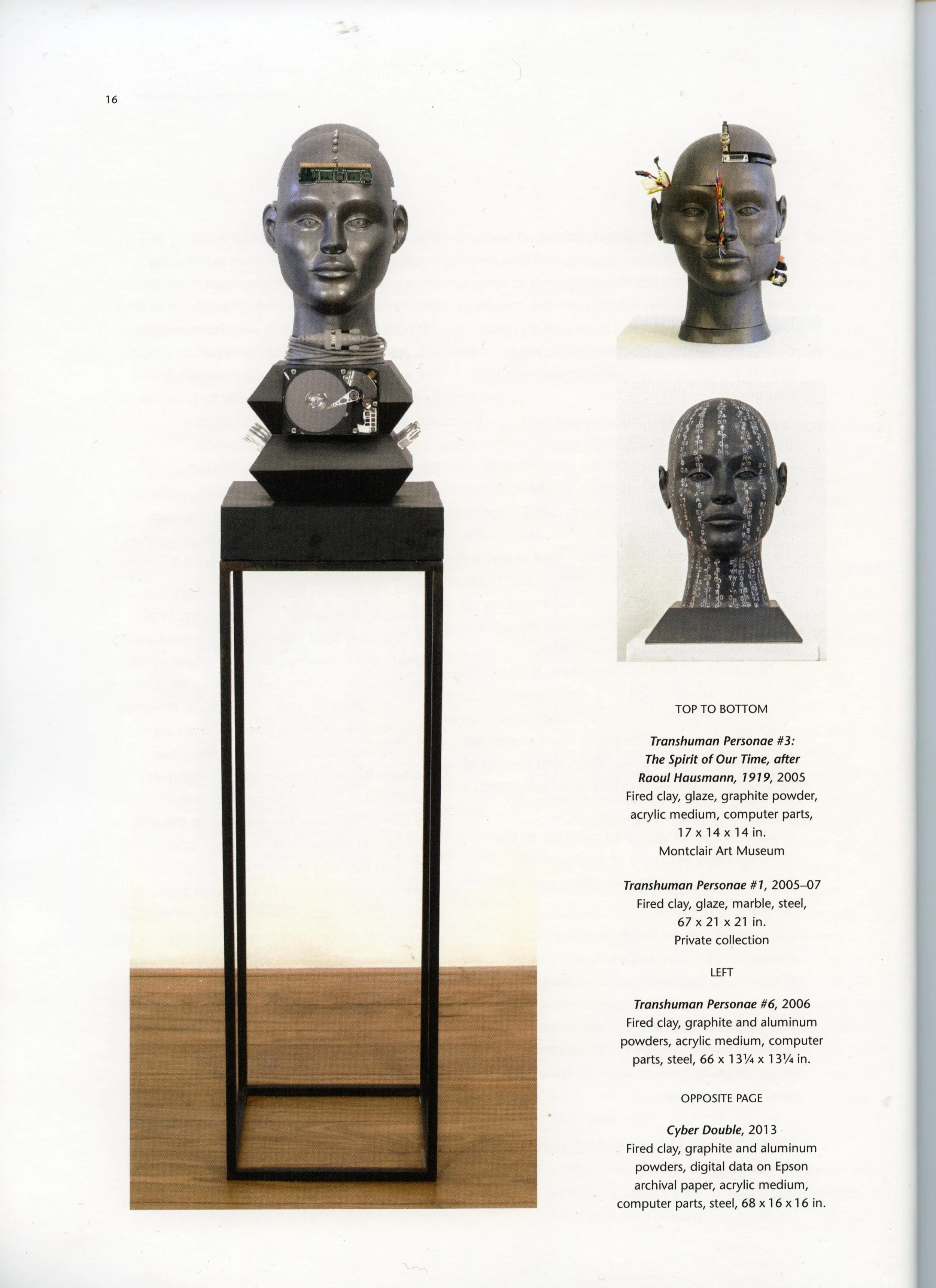

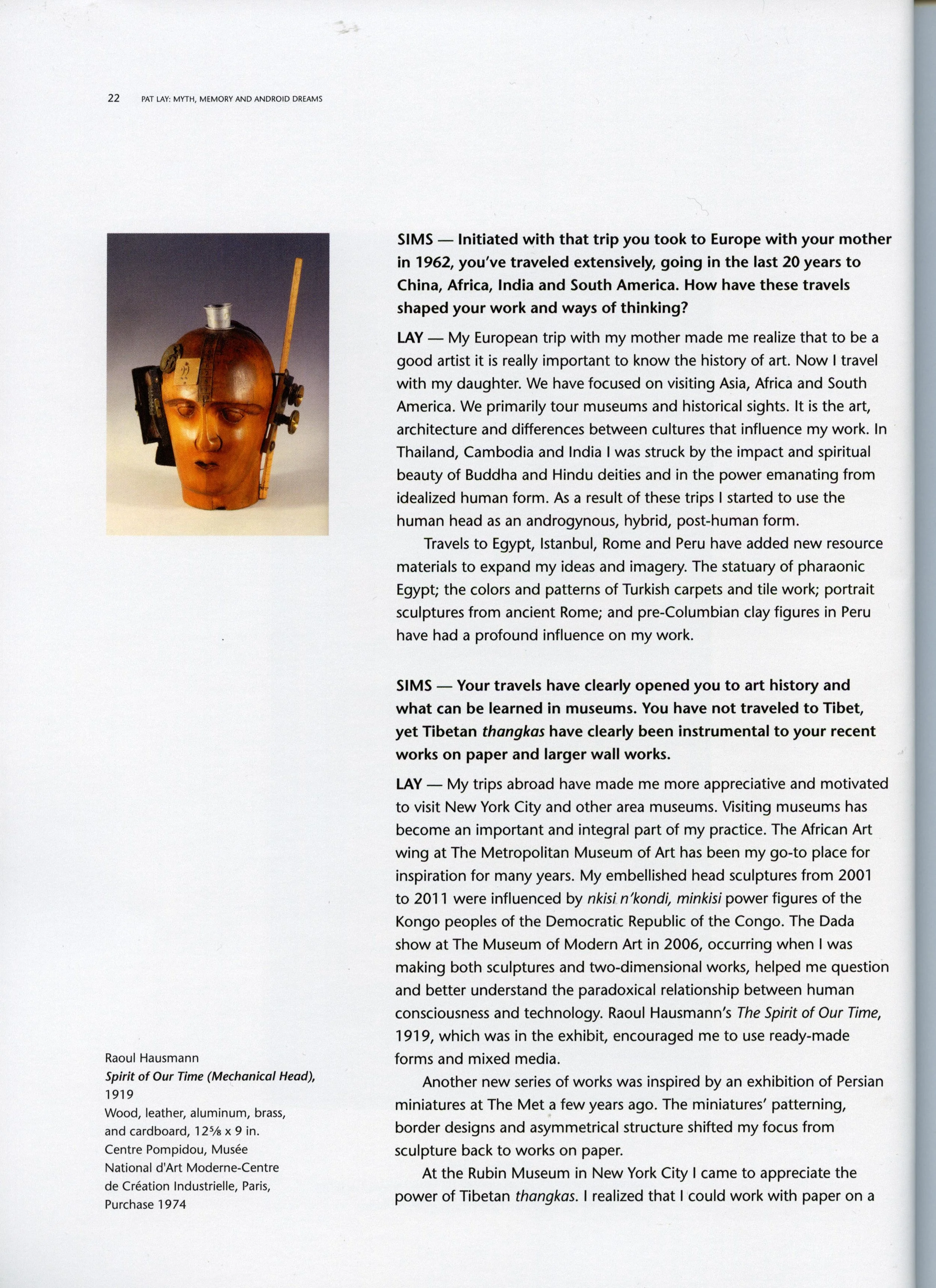

My foreign trips have made me more appreciative and motivated to visit NYC and other area museums. Visiting museums has become an important and integral part of my practice. The African Art wing at the Metropolitan Museum has been my go-to place for inspiration for many years. My embellished head sculptures from 2001 to 2011 were influenced by Nkisi n’kondi/Minkisi power figures of the Kongo peoples of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The DADA show at MOMA in 2006, occurring when I was making both sculptures and two-dimensional works, helped me question and better understand the paradoxical relationship between human consciousness and technology. Raoul Hausmann’s The Spirit of our Time, 1919, which was in the exhibit, encouraged me use readymade forms and mixed media.

Another new series of works were inspired by an exhibition of Persian miniatures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few years ago. The miniatures’ patterning, border designs, and asymmetrical structure shifted my focus from sculpture back to works on paper.

At Rubin Museum in New York City I came to appreciate the power of Tibetan thangkas. I realized that I could work with paper in a much larger scale, up to 96 x 48 inches and turn a religious icon, the Tibetan thangka, into a contemporary aesthetic abstract composition that serenely captures our world of technological advancement. At the same time the scroll format was a practical way to make large works easily portable. Meditating on the past, present, and future, my scrolls and mixed media figurative sculptures question and critique our paradoxical relationship and obsession with technology and what it now means to be human.

SIMS: Many of the artists you mention as influential are men, are there artists who are women you have been influenced by?

LAY: Louise Nevelson was an important role model in the late 1960s when I was in graduate school, as were Eva Hesse, Beverly Pepper, and Barbara Hepworth. More recently, the bound leather mask heads made by Nancy Grossman from the 1960s through to the 1980s have intrigued me and influenced my work

SIMS: Let’s talk more about gender in your work and how that might have played into your artistic practice in the 1960s, 70s and ‘80s, and where you are now on some of those issues.

LAY: I was definitely in a different place in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. I got married in 1963 when I was 21. My husband, the artist Kaare Rafoss, and I felt like we grew up together. We were at Pratt Institute at the same time. While he studied painting at Yale Graduate School, I had a teaching job, and then he taught while I did my graduate studies at Rochester Institute of Technology. We were equal in our relationship. We both had the same degrees, and we both took college teaching jobs after graduate school. We felt very independent and yet shared everything. So there was no gender issue or bias for us. Yet in the art world women and their art were considered less important and respected.

Kaare and I moved to a loft on Broome Street in SoHo in 1969. Soon after that I became a member of a women’s consciousness-raising group. While the women’s movement in New York in the 60’s and 70’s had a political agenda, my focus was on making art that was personal and less concerned with social issues.

SIMS: Are you conscious of aspects of your work that address your gender and address issues of sexuality? Do you think someone could look at your work and say a woman did this work?

LAY: I don’t think my work particularly addresses issues of gender or sexuality. I think it’s very formal. Due to their palette and delicacy, some of the recent scroll works might seem to some people more feminine. For most of my career I consciously tried to make work that was not gender specific or feminine, as I felt it would be dismissed. Now I see male artists whose work looks very “feminine.” It’s just not an issue any more: I and others do what each one of us wants.

SIMS: You talked about being married since you were 21, having a happy marriage, and never feeling in any way that your life is compromised in that relationship or in the bond of marriage. What is it like to not only have parents who are artists, but to have a husband who’s an artist?

Kaare’s artwork is very different from mine, but we’ve also come closer in terms of our art and its characteristics. I’ve learned and taken ideas from him. He’s taken ideas from me. For instance, I’ve been using the grid for many, many years. I went away from the grid for a while, and then I went back to it because Kaare began using it, and it became clear to me that it was a structure that I wanted to work with again. We try to stay out of each other’s studios while we are working. But sometimes I will ask him to critique the work. I also frequently ask him for technical help. We have had opportunities to show together in a two-person show, but Kaare is not interested in doing that.

Recently we have been sharing a studio assistant. Szilvia Revesz has worked for us for about 12 years. Originally she was Kaare’s assistant and in the past six years she has also been working with me on my works on paper. Szilvia is a talented artist with a high level of technical skill and knowledge. She is an essential component of my studio practice.

SIMS: You have lived, worked, and now are having a major career survey in New Jersey: does living and working in the state play any major role in your work?

LAY: I can’t say that New Jersey or its art world per se play a role in my work. We lived on Broome Street in SoHo for twelve years before moving to Jersey City in 1981. We moved to Jersey City when we realized we could afford to buy two connected buildings and an adjoining open lot. It gave us large living and workspaces. It is quiet and has lots of light. We have a garden, which is very important to me, and we can park our car in front of our house. My daughter and her family now live in their own apartment in our buildings. I can go sailing a few minutes away from where I live.

When we moved to New Jersey, I had already been teaching in at Montclair State University for almost a decade. The moment I started teaching and then assuming a more administrative role at Montclair State, where I worked from 1972 to 2014, I was thought of as a New Jersey artist. I had a solo show at the New Jersey State Museum in 1973. I was in a biennial exhibition at the Newark Museum in 1977. In the ‘70s I was submitting proposals for New Jersey’s very active public art commissions program. Forwarding my career was much easier in New Jersey than New York. That went on through the ‘80s, by then I felt I had shown in every museum in New Jersey, yet sold very little art and hadn’t achieved any lasting recognition. So I thought now what?

New York City is the place where things happen. Our friends are all artists, and everything that we do socially and professionally has to do with the art world. For us and others here, Jersey City is effectively NYC’s 6th borough. From our neighborhood in Jersey City it takes us literally five minutes to get to downtown Manhattan. If we have a reason to go to NYC more than once in a day, we do so. I don’t feel like I ever left Manhattan.

SIMS: You have been considering this survey of your work for some time; what have you learned about your art and yourself that you did not know or acknowledge before?

LAY: I have been working on my archives in preparation for this show. It is interesting to see the threads that carry through all of the work. The grid was important to me forty-five years ago, and it is still the structure that I choose to work within now. Another constant is art history, which I have continued to rely on for inspiration.

I have also learned more about my family history and the central role that art and creativity have played. It has all been like putting together the pieces of a puzzle.

SIMS: Given the distinct chapters of your art, as you look back with the organization of this survey, how has your attitude about your work and its developments changed? Do you see unity or disconnection? What has been the impact of having to look back when so often you’ve looked forward to the next chapter of your work?

LAY: Those are hard questions to answer, maybe I will know better when all the work installed at the gallery. I do know that when I get to a certain point with a body of work, that I’m finished with it, and I want to introduce something new. So I look out for what will be the next thing.

SIMS: You probably have had colleagues, artist friends in the New York art world, who have had significant success. It hasn’t seemed to discourage you that you haven’t had that much commercial success. Do you think that economic and critical success strengthens a person or an artist or is not really that important?

LAY: I am confident that I am doing good work, but it is important to me to get some art world recognition. Financial success from selling the work is not so important because teaching gave us a very secure living, we were able to buy in Jersey City the space we need to live and work.

I always thought the ideal situation would be to have one’s art support itself. But financial success can make artists turn their work into a business, and in the process they loose the freedom to change and evolve. People expect certain kinds of work and so you just keep making it. It’s hard to move ahead with new ideas because you can just keep producing and producing.

SIMS: Now that your teaching practice has ended, has more time and the full focus you can have freed or opened up your art making and thinking?

LAY: Yes, I can focus. I don’t feel pressure to rush the work. I have time to experiment. I have thought about working with paper pulp, but I have never had the time to experiment with it. While teaching I felt that I didn’t have the time to deal with the business side of being an artist: self-promotion and networking. I chose to go to the studio rather than promote the work. Family, teaching, and art making always came before self-promotion and socializing. Now I try to structure my time so that more time is allotted for the business of art.

SIMS: How does being older impact on the role that art has in your life and that you now are looking back on the whole span of your career?

LAY: I am not done yet. I will continue to make art as long as I am able. I am happiest when I am working in my studio.

It remains very hard to get a NY gallery, but it’s remains the best way for my work to be placed in collections and preserved.

I would love to say that I would have chosen not to teach and just be a full-time artist, but I know I could not have done that. We have so many artist friends that are in economic distress at this point. They can no longer afford to live in New York City. Many have no retirement income or health insurance. Basic good luck and the choices we made have allowed us to feel financially secure, which makes me feel good about how I have lived as an artist.

Naves, Mario; Now at New York’s Galleries, ‘Everything in the World’ and More, New York Sun, March 22, 2024

nysun.co

Mario Naves, March 22, 2024

Pat Lay, ‘Nesting Bot X2C2’ (2024). Via Elza Kayal Gallery

Excerpt from NY Sun Article:

Human beings or, rather, the compromises to which humankind is invariably confronted, are at the center of “Multidimensional,” an array of prints, collages, and sculptures by Pat Lay at Elza Kayal Gallery. A veteran of the New York City art scene — she was, lest we forget, featured in the 1975 edition of the Whitney Biennial — Ms. Lay has long been exploring the relationship between the technological and the organic, the machine-made and the hand-crafted.

Ms. Lay’s investigation into artificial intelligence and human integrity precedes our current fixation with the topic. She addresses the issue not with alarm or hyperbole, but with subtlety and wit, particularly in a series of supple ceramic biomorphs that are punctuated by repurposed computer parts.

The best of the bunch is “Nesting Bot X2C2” (2024), in which a bulbous form, glazed a rich burnt orange, is propped up by an accumulation of braces colored a milky white. Here the animism at the center of Ms. Lay’s vision is rendered precarious — as if the scaffolding on which her “hybrid taxonomy” snuggles is as sentient and fragile as its charge.

McCall, Tris; Pat Lay: “Hybrid”, eye level, February 10, 2025

eye-level.net

Tris McCall, February 10, 2025

The sculptor, printmaker and longtime contributor to the JC art scene locates sacred reverberations in the heart of the mainframe.

And through the wire: Pat Lay's "Transhuman Personae"

Somewhere beyond the firmament, God is probably growing jealous of artificial intelligence. Not its omnipotence — so far, it hasn’t shown itself capable of much more than plagiarism — but by people’s unshakable belief in it. We’ll accept answers to questions without demanding citations from the database we’re consulting. We encourage it to write for us, calculate for us, and think for us. For no reason at all, we will believe that the oracle we’re consulting is impartial: a pool of accumulated human wisdom we can sip from, rather than dogma influenced, or straight-up supplied, by the high priests in the boardrooms of tech companies. Credulousness is the residue of blind worship, and lately, we’ve been kneeling before a digital altar with our eyes shut. Faith in magic isn’t waning. It’s moving online.

In our charitable moments, we’ve got a name for this creed: transhumanism. This is what we sometimes call the outsourcing of our basic faculties to machinery. It may seem ironic that one of the oldest artists in Jersey City is one of the most persistent investigators of the aesthetics of the transhuman, but really, it’s an indication of how long the fantasy of computer-enhanced existence has been around. Sculptor, printmaker, and experimentalist Pat Lay is fascinated by chips, wires, and circuit-boards, and her heady work crackles with digital mystery. She’s been a consistent observer of the strange similarities between digital design and ancient symbology.

“Hybrid,” a new show that makes the austere interior of the Lemmerman Gallery at NJCU (2039 Kennedy Blvd.) feel more than a bit like a mainframe, turns the machine inside out and exposes its guts. In so doing, Lay tells us something unnerving about how we’ve been wired, and re-wired, by the plugged-in world we’ve made. Our reliance on an invisible grid to guide us is the closest thing we’ve got to a 21st century popular religion, and thus it’s not too much of an exaggeration to call “Hybrid” an exhibition of religious art.

In “Hybrid,” Pat Lay even reimagines the soul as something that might be fused with (and transformed by) a physical motor. The artist affixes a piece of computer junk — an old fan, or a little turbine, or an array of plastic prongs — to a ball of clay about the size of a globe. Then she tints, shapes, and glazes the sculpture in a manner that makes it seem like the discarded computer part and the sculpted earth are indivisible. Cleverly, Lay allows the dimensions and visual attitude of the industrial waste to influence her design decisions for the color, angles, dimensions, and personality of the clay body of the piece. She calls these “soulbots,” and though we’re tempted to see the metal and plastic as the “bot” and the earth and minerals as the “soul,” it’s entirely possible that, for Lay, it’s the other way around.

Lay nests her soulbots all around the Lemmerman, where they sprout like gourds and squat like wintering waterfowl, and exude self-satisfaction and integrity. That which is immortal and transcendent, they seem to say, can no longer be separated from the manufactured environment. We’re part eternal organic being and part android, and it’s getting harder to tell which part is which.

Digital fingerprints: Small pieces by Pat Lay.

This ambiguity continues with a pair of “Transhuman Personae” sculptures: clay busts of impassive bald-headed men sprouting wires and diodes from their faces as if they’re robotic chia pets. Lay has fashioned them with compartments in their crania and their cheeks, and stuffed them with cables and connections. These are golems as they might be fashioned by Radio Shack or Mikey’s Hookup, and as they stare at us with gears where their third eyes ought to be, they radiate a curious kind of contentment. They seem ready — for the future, or a fight, or for a hard drive crash. Their alacrity might be a matter of electricity and rubber, but it comes through powerfully, and it achieves the intensity most frequently seen in works of sacred art. Lay’s clay transhumans will probably remind you of Dr. Manhattan from the Watchmen and other laser-eyed sci-fi characters, but the frayed connections and chipboards that ring their necks also call back to North and Mesoamerican sculptures used in ritual practice, and the symmetry and self-possession suggest ancient depictions of Siddhartha Gautama. For these half-robots, maybe enlightenment is simply a matter of turning on the current.

Overtones of Buddhism are detectable in the two-dimensional work on display, too. Lay’s Kozo paper wall-hangings, some as big as altarpieces, are collages of images of computer parts and drives, doubled, mirrored, and saturated with color. The patterns are instantly recognizable as machine-derived, but they also hint of Himalayan sand-painted mandalas and Navajo blankets. This is the motherboard as iconostasis, and it does invite quiet reverence from the viewer. Lay has even given these pieces a handle that whispers of the temple: she calls them scrolls.

This is appropriate. Scrolls are handled and interpreted by priests, consulted only when necessary, and put away out of the reach of the parishioners once the liturgy is over. Most of us have no idea how the devices we rely on operate. Unless we’re electrical engineers, we’re absolutely mystified when we peek under the hood. Holy geometry is as good an explanation as any for the wizardry we encounter when we operate our computers. As Arthur C. Clarke — someone who surely would have enjoyed “Hybrid” — reminded us, sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. We reached that level of advancement long ago.

Yet innovation happens fast, and as it change happen, our ideas about transhumanism change, too. The funny thing about “Hybrid” is that the technology in the show already feels archaic. USB and printer connections are antiques in a wireless world; the flash drives that dangle from the heads of the busts are as anachronistic as a bone necklace. Many young people who are perpetually online will never see a chip. Cables have been cut, hardware has turned into vaporware, and interfaces have shrunk to the brink of invisibility. The wire as a metaphor for connectivity has given way, replaced by the five bars on the top corner of the phone, and the future transhuman subject, passively caught in the strands of an invisible web, will not resemble a cyborg. He’ll be indistinguishable from a man on the street in the age before computers. Only the structure of his consciousness will be different.

And even that is debatable. Technology has changed the speed of our communication and the tenor of our interactions. I am not sure it has laid a glove on the human soul. We're the same trouble that we’ve always been, and in pretty much the same way we've always been, no matter what gadgets we’re presently hooked on. Artificial intelligence has been advertised as transformative, and perhaps in its purest form it is; but the way we’ve been using it is as human as any other kind of piracy throughout history. Pat Lay is absolutely right to locate a spiritual dimension in our quest to be more than what we are, and to identify technology as the means by which optimists hope to get there. Her delightful little soulbots, smooth, balanced, and perfectly integrated, with no visible dissonance between the mechanical and the organic, are an expression of a real aspiration. Her hypnotic vision of sacred patterns in the microchips is a gesture of hope that the digital future into which we’re headed might be informed by the wisdom of old.

Perhaps it will be. Maybe there are enough traces of the holy in the body of our machines to make our new religion as spiritually satisfying as our old ones were. But this penitent wishes we had better gods to worship.

(“Hybrid” is on view at the Lemmerman Gallery on the third floor of Hepburn Hall, the prettiest building on the NJCU campus and the one you’re least likely to miss. The gallery is open to the public from noon until 5 p.m. every weekday. It’s a free show.)

Tris McCall, Feburary 10, 2025

Goodman, Jonathan; Sculpture Magazine, September, Review of Aljira Exhibition

SCULPTURE MAGAZINE: PAT LAY (2016)

By Jonathan Goodman

Originally published in Sculpture magazine, September 2016, Vol. 35, No. 7

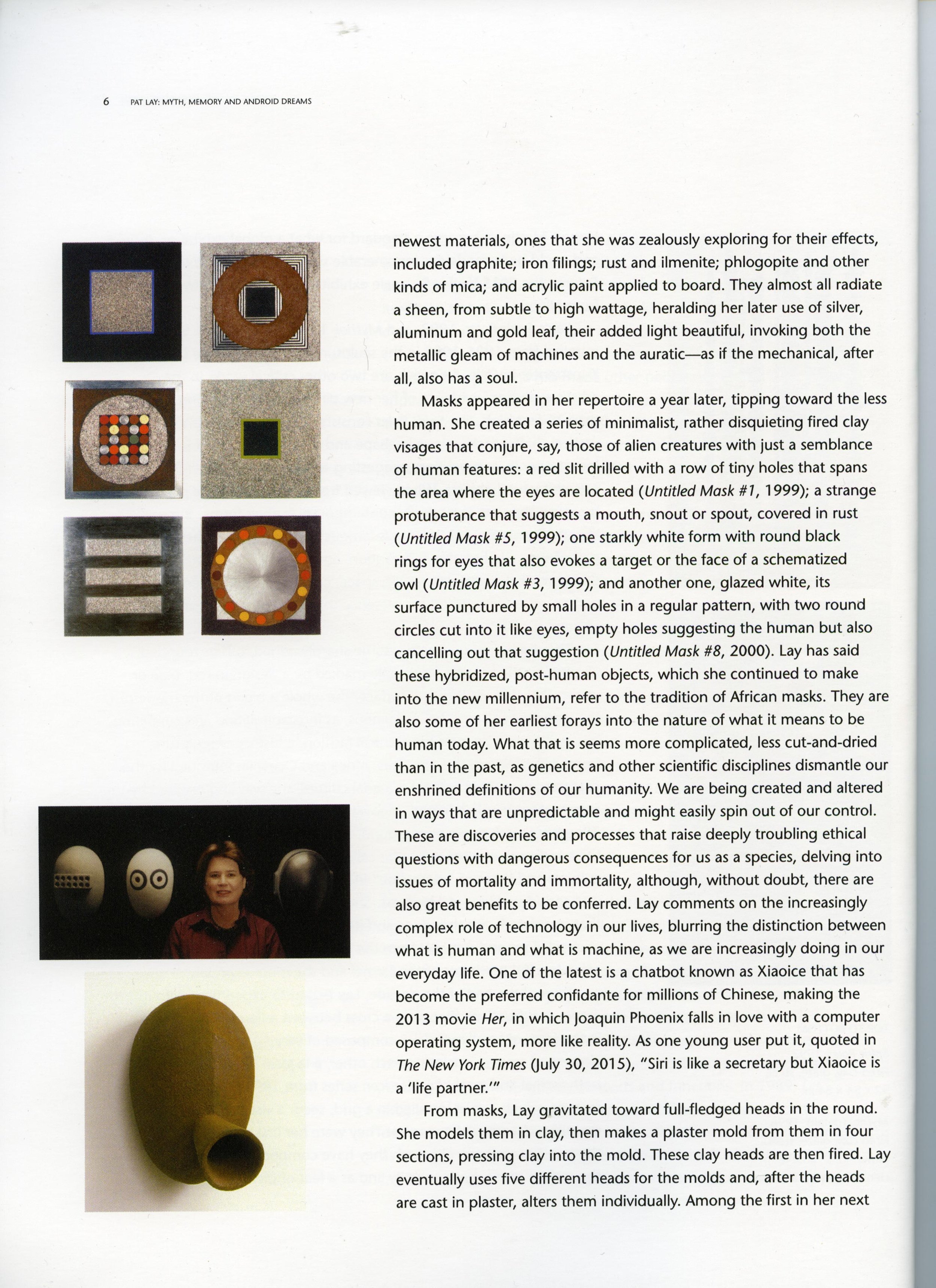

Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art, Newark, NJ

Pat Lay, who retired not long ago from the MFA program she founded at Montclair State University, recently mounted a major retrospective at Aljira, a prominent nonprofit space in downtown Newark. Curated by Lilly Wei, the show covered decades of work, from late-’60s clay pieces to works made as recently as 2015. There was a good mix of three-dimensional work, including archival prints whose exquisite symmetry is constructed from computer-parts imagery, but Lay has acknowledged that the true turn of her work is sculptural.

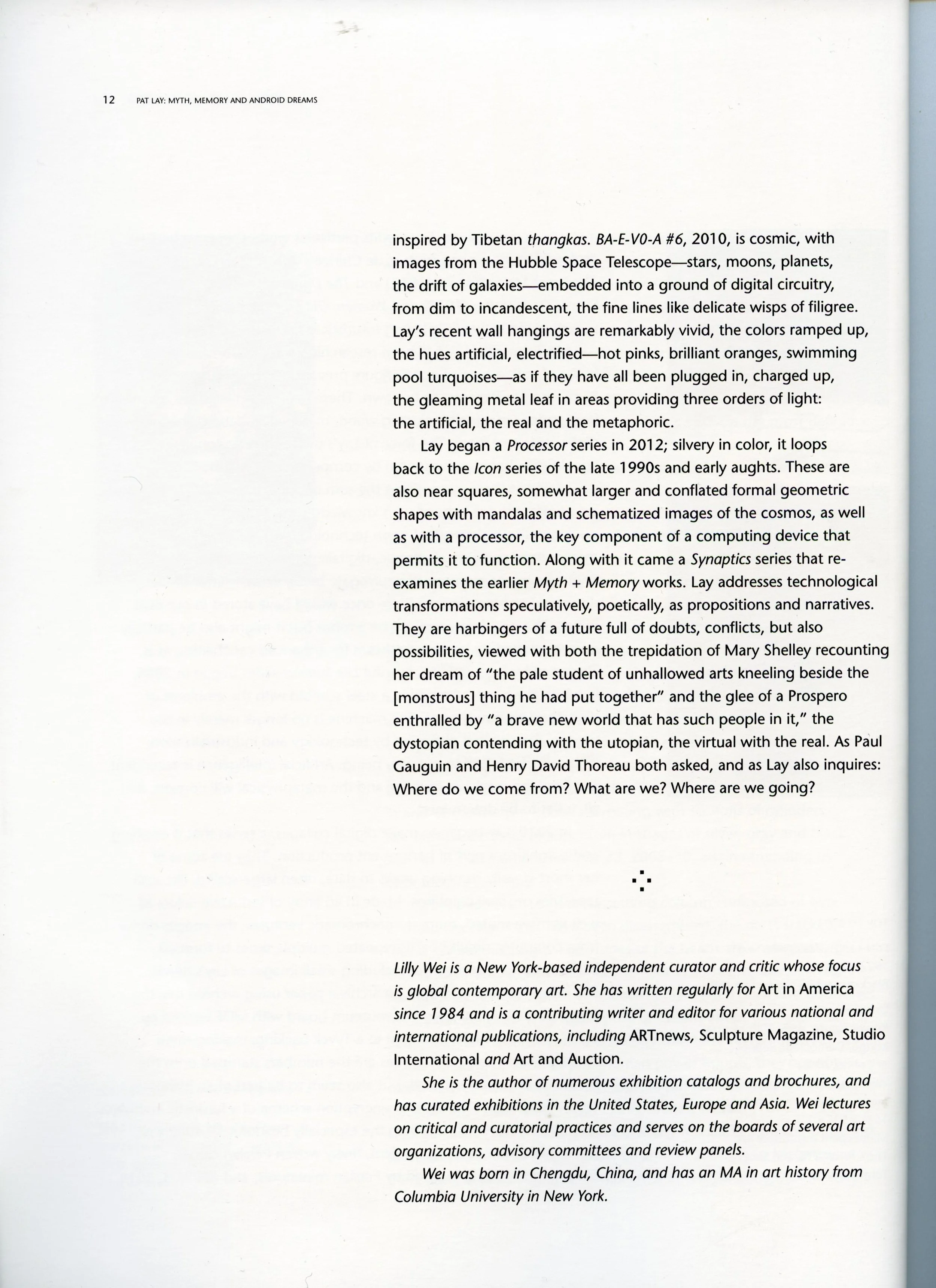

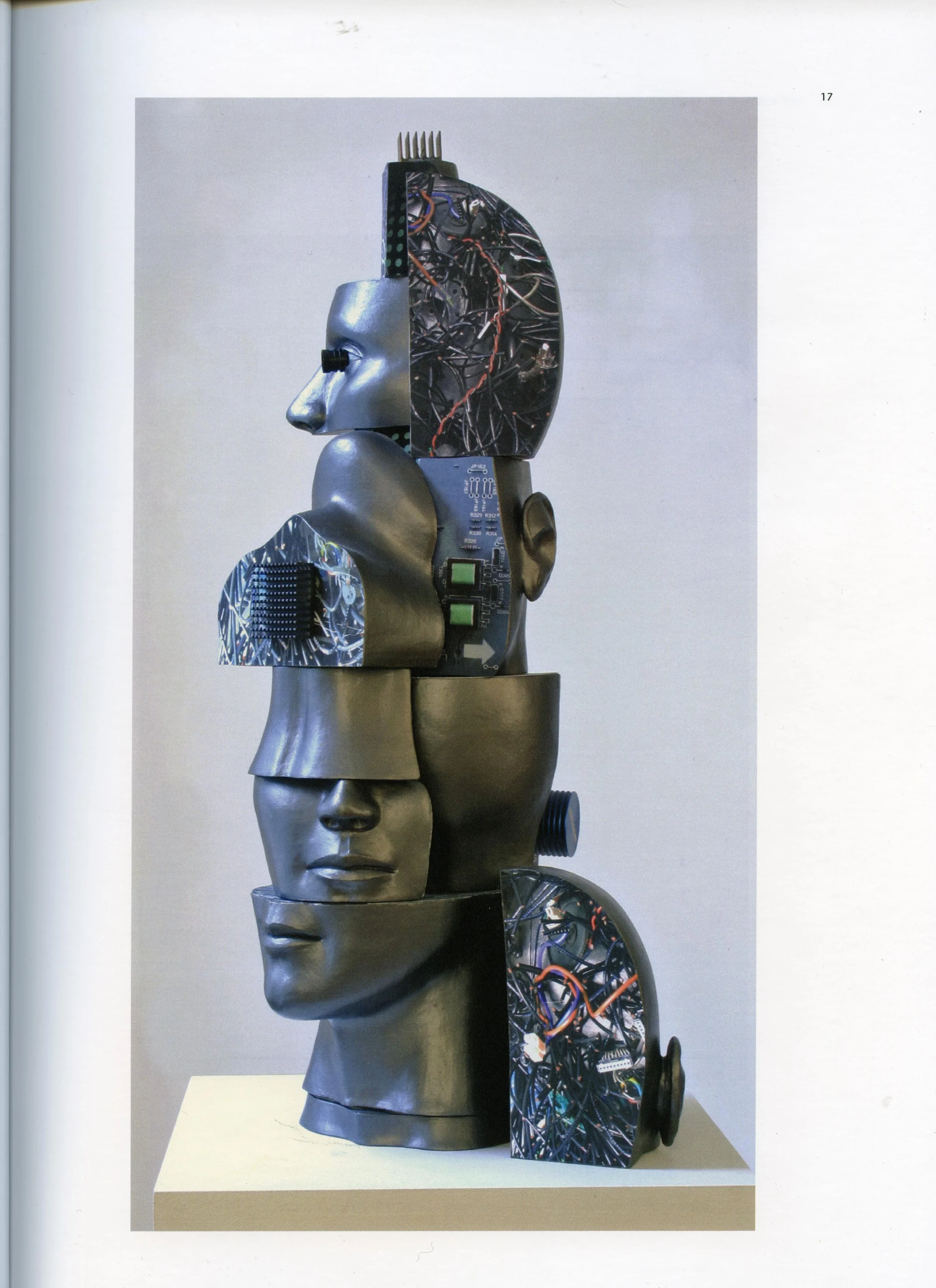

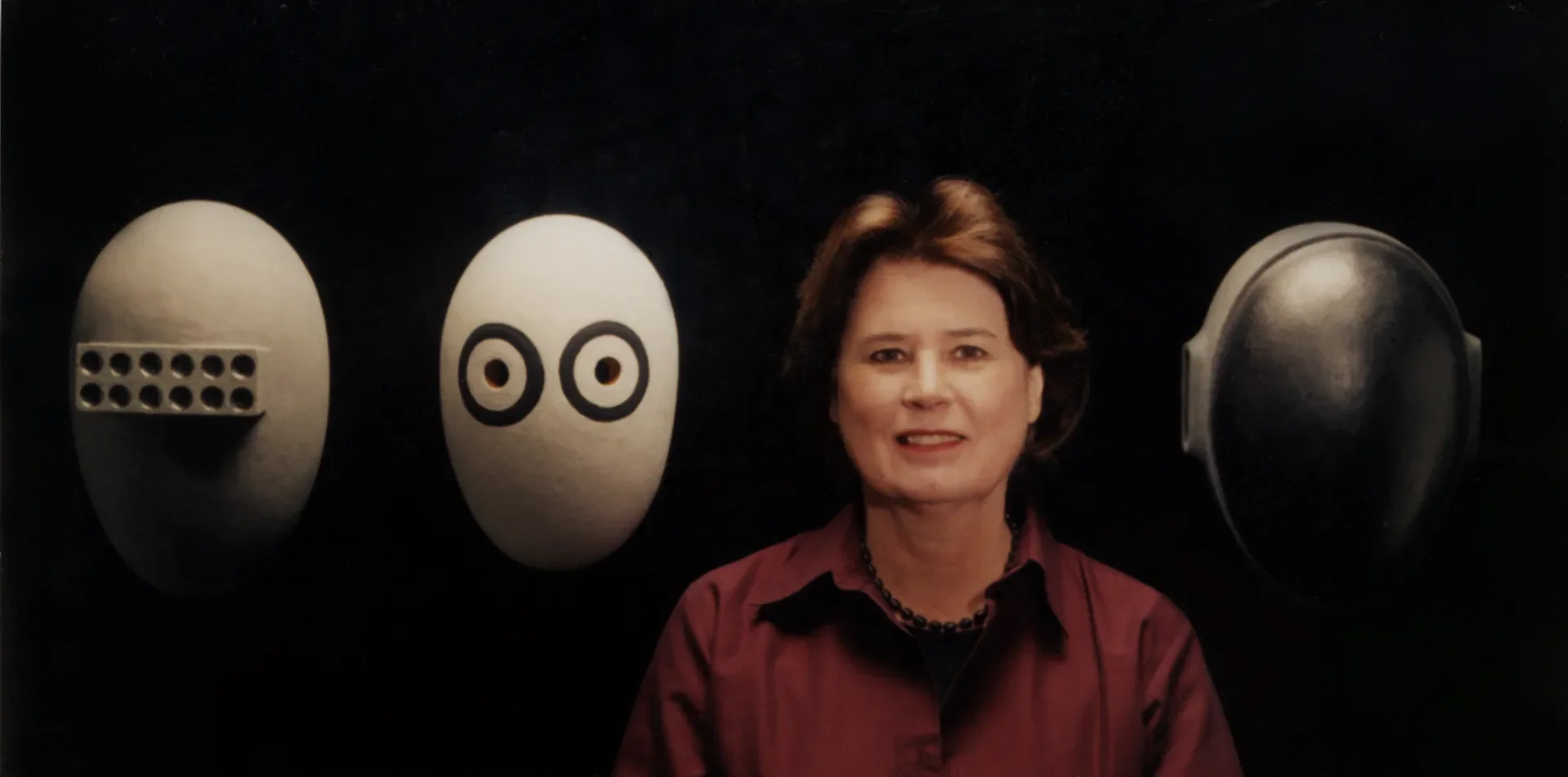

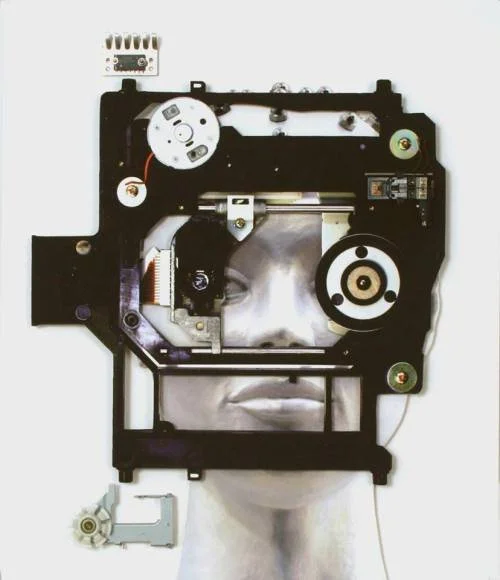

The show included a fine array of three-dimensional objects, ranging from a tile-work installation influenced by Noguchi to African-inspired totems, to gender-ambiguous cyborg heads, from whose crowns issue Medusa-like wires with variously colored wrappings. Lay’s art is endlessly various, which indicates a curious cast of mind. She combines the very old with the very new in ways that push contemporary art forward, toward a statement that covers art history as well as contemporary sensibilities.

An untitled 1975 work, shown in the Whitney Biennial that same year, recalls Noguchi’s sunken garden at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale. Like Noguchi’s garden, Lay’s (smaller) installation has images on top of a flat surface — in this case, a plane made of ceramic tile. A circle of brown cloth, a pyramid, and a translucent box embellish the exterior, complicating the plainness of the surface. Done some 40 years ago, it is strong and independent interpretation of the Japanese sculptor, yet it doesn’t presage the work that Lay would produce in the future.

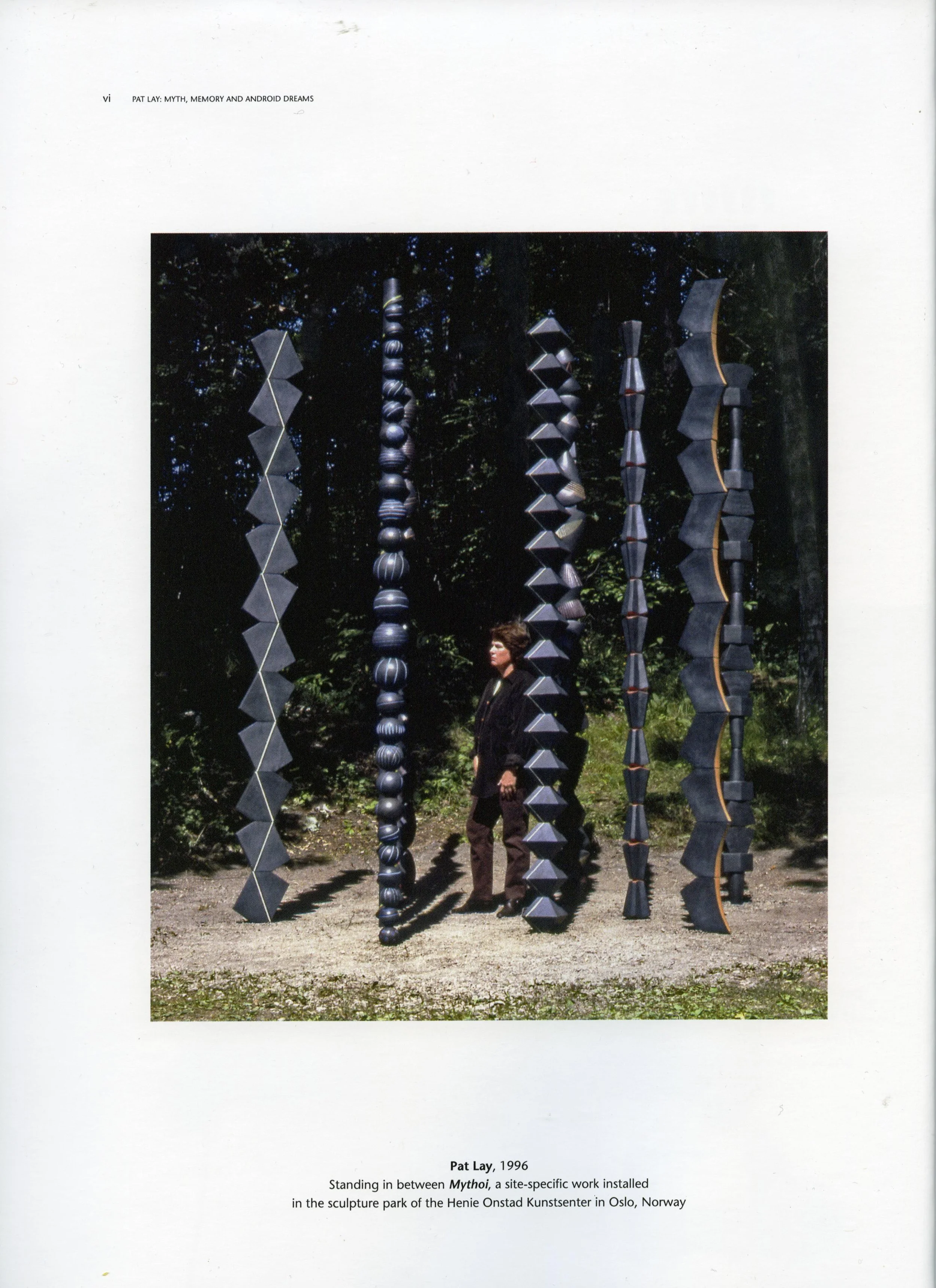

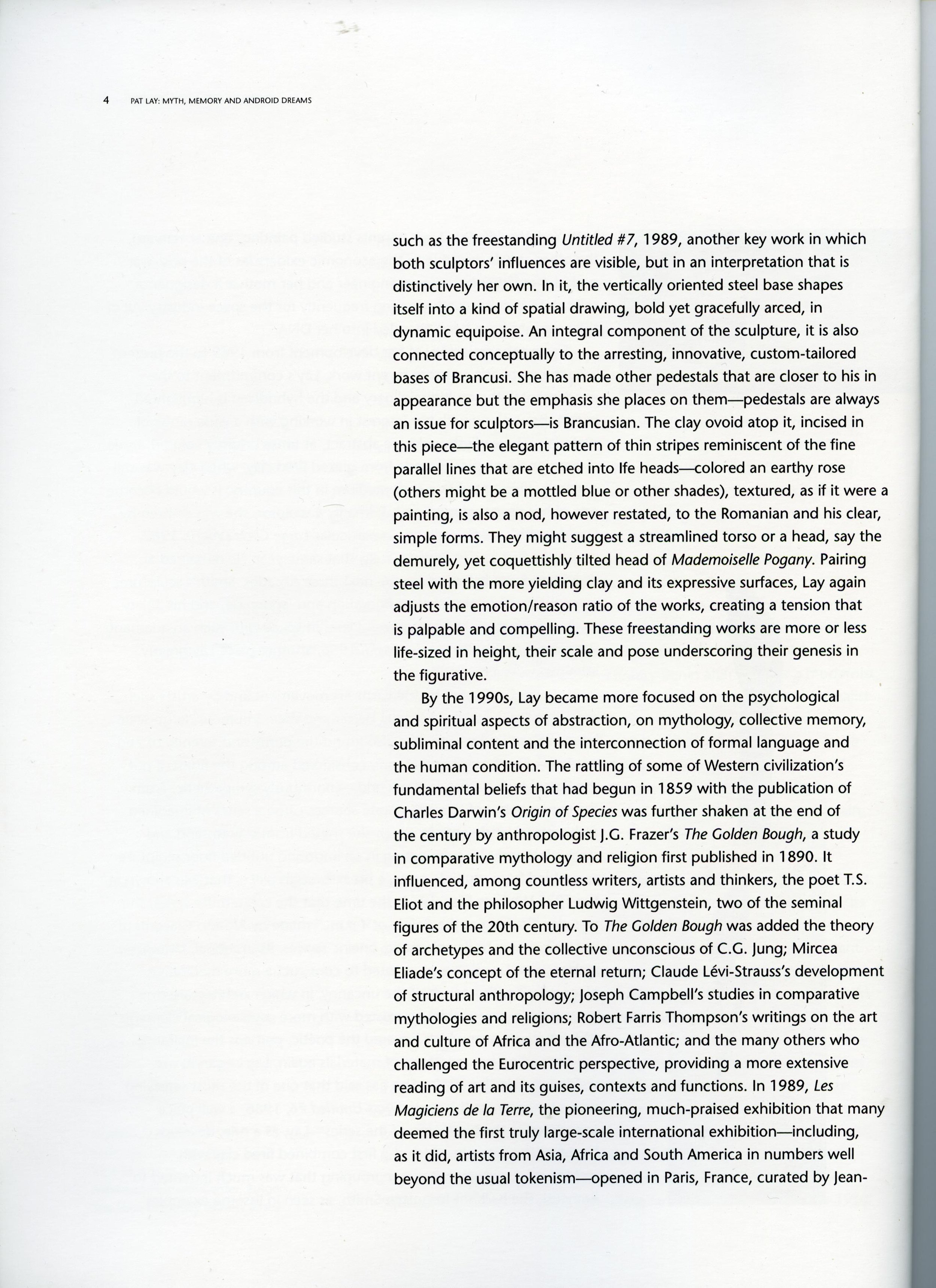

Among her most interesting and strongest works is Mythoi (1996), a group of fired-clay totems, first shown outdoors in Oslo, Norway. Consisting of more than 10 tall, narrow forms composed of repeating elements, the installation looks like a combination of high Modernism and African art. The fusion is genuinely potent. Installed towards the back of the gallery, Mythoi established an atmosphere of ritual power not often found in Western sculpture.

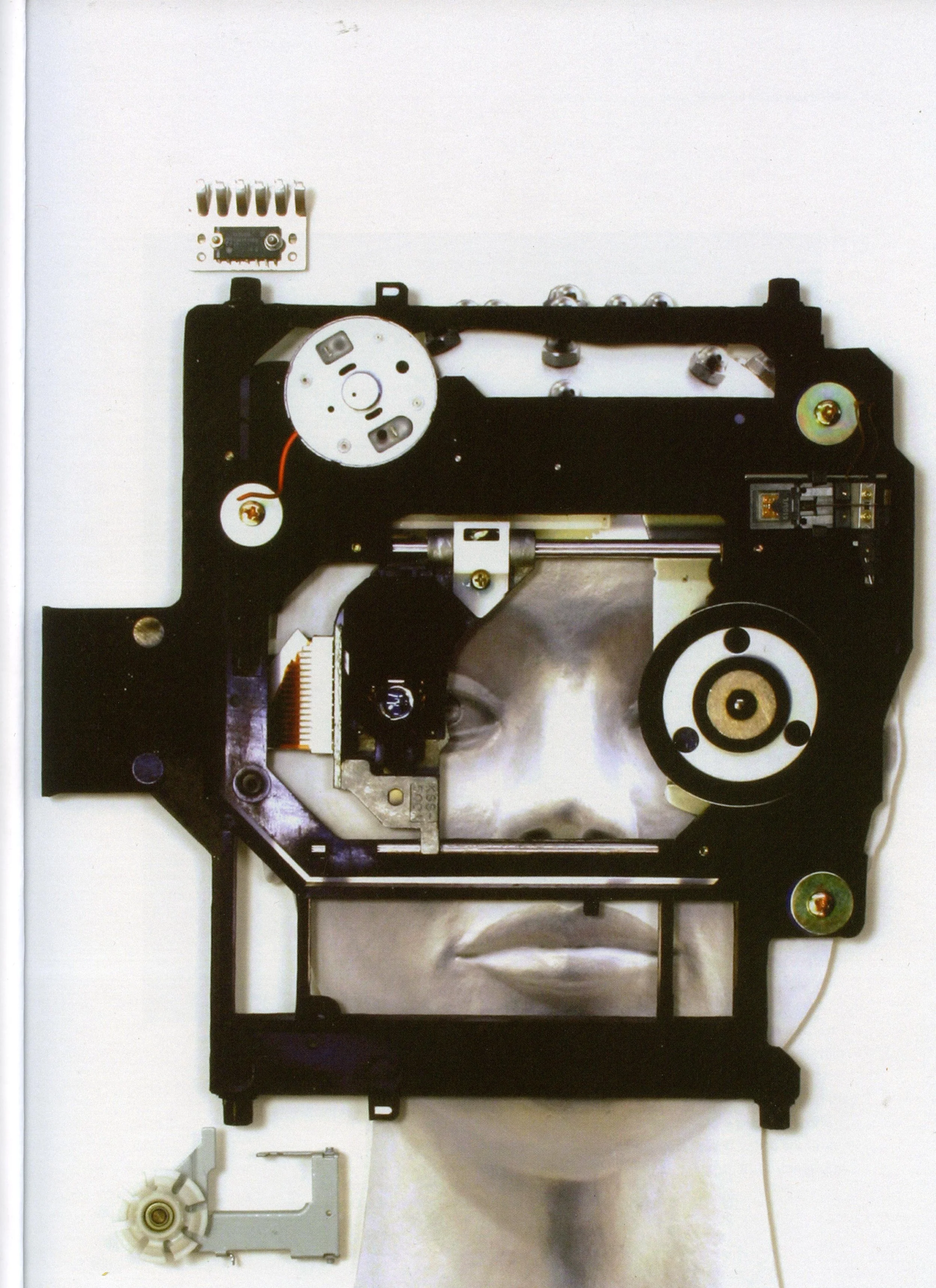

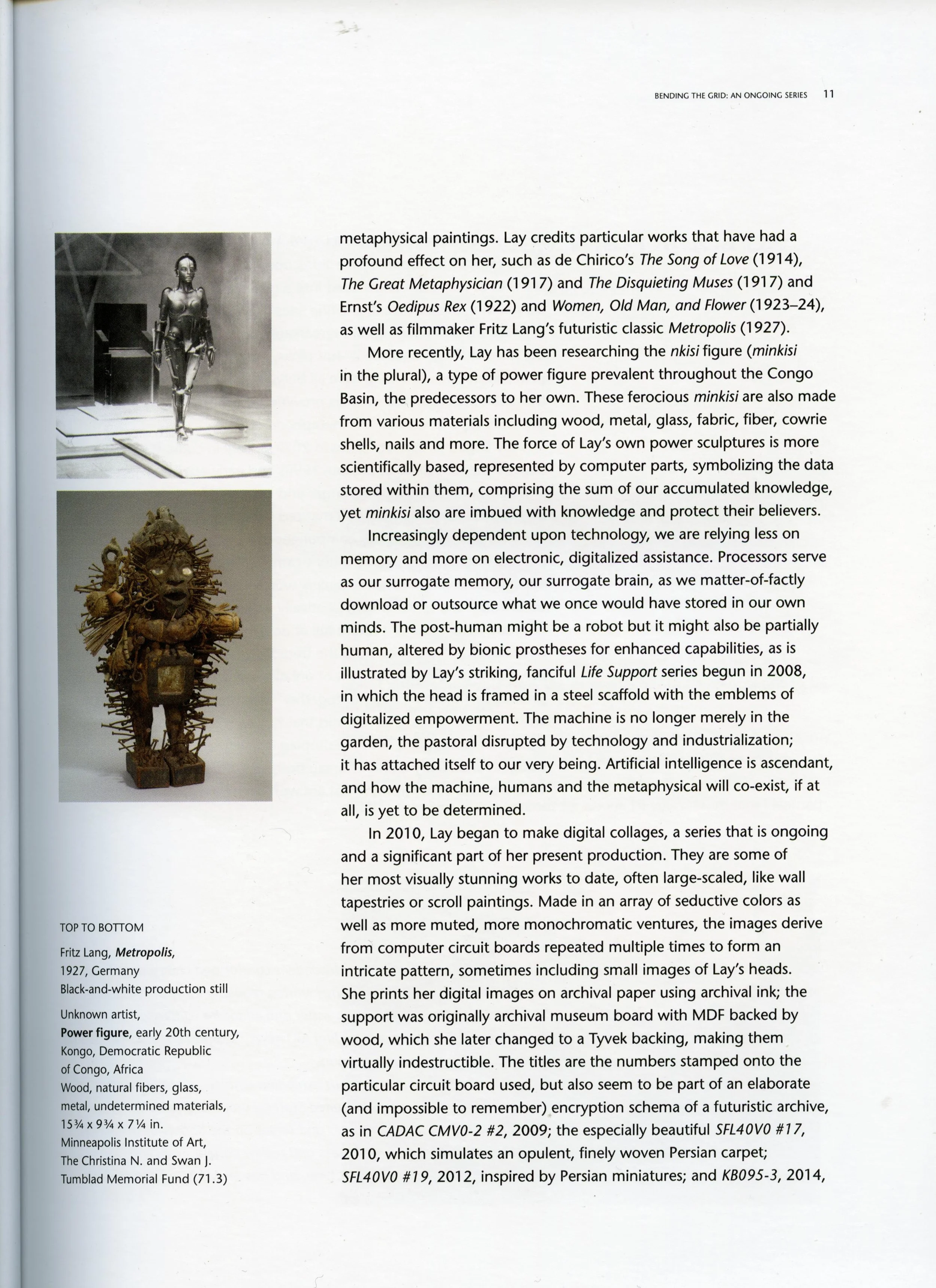

Lay’s high-tech heads have a close precedent in Raoul Hausmann’s 1919 bust Spirit of Our Time (Mechanical Head), which is made of wood, leather, aluminum, brass, and cardboard with various objects. In a similar manner, Lay’s androgynous clay heads are adorned with colored wire and computer parts, as in Transhuman Personae No. 11 (2010). Supported by a computer tripod, the wires fall to the ground. In conversation, Lay has indicated the influence of African nkisi, sculptural objects inhabited by spirits. These nkisi are for spirits of our time. Lay, who began to travel later in life, looks to other cultures for inspiration, successfully transforming influence into resonant statements for contemporary African audiences.

McCall, Tris; Art Review: Pat Lay at the Dvora Pop-up Gallery, Jersey City Times, February 28

"DM423161212" by Pat Lay

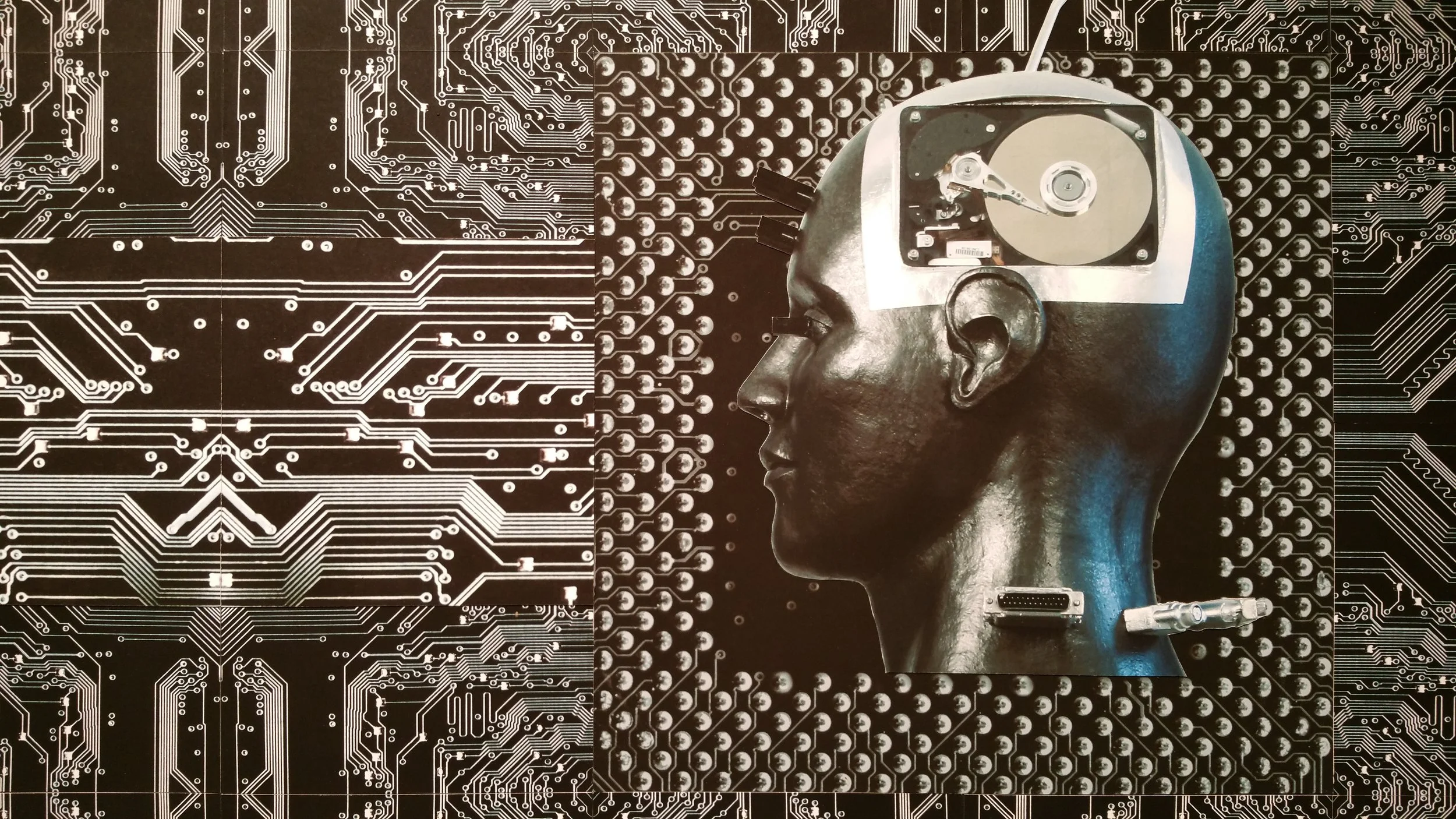

If you’ve ever had a computer spill its guts to you, you know what a shattering experience it can be. The surfaces of video cards and chipboards are great riddles in titanium, wire, and plastic. Dots and twisting parallel lines, bright colors and silent black rectangles: It’s all in there, hidden behind the screen you may be looking at right now. Run electricity through it, and the magic begins. But unless you’re an engineer, there’s very little chance that you understand the meanings of the markings on the chips and drives. They’re as inscrutable — and as beautiful — as hieroglyphics or cuneiform characters carved into rocks.

Many visual artists have been struck by the accidental aesthetic of electronic components. Few, however, have taken that interest quite as far as Pat Lay. Visiting “Exquisite Logic,” her show at the Dvora Pop-up Gallery in the Powerhouse Arts District, is a bit like stepping into a mainframe. Lay takes byzantine images of circuit boards, manipulates and enhances them, and goes large with them — sometimes as large as a tapestry or a Persian rug. Even the materials she uses to make her prints and collages have technical-sounding names: MDF cradled paper, Tyvek backing, metallic ink. Instead of handles, she’s assigned serial-codes to them: “B53K477-1,” “B54AAA0468B,” etc. To an non-artist, it’s all as arcane as a liturgy in Latin.

“DM422161212” by Pat Lay

From these elements, Lay has conjured something subtly familiar and maybe even deeply human. Lay calls many of these images “digital mandalas,” and many of them do display the symmetry and the near-tessellated quality associated with traditional indian art. Modern mandalas are often used as relaxation tools, but for centuries they were associated with devotional practice. Here, the Buddha is gone missing, replaced by a microchip.

“Exquisite Logic” is not a simple statement about the loss of spiritual intensity amidst the rise of the machines. Pat Lay has far too much respect for computers for anything as vulgar as that. Rather, her work whispers about the way in which Techne always seems to draw on the symbolic language of religion. By tracing connections between motherboards and sacred painting, Silicon Valley and sadhana, Lay’s art brings the computer and the temple into alignment. Both are sites of magic and wonder. Both are favored by visionaries, enlightenment-seekers, and thrill-riders.

In order to achieve this effect, Lay goes heavy on eye-popping techniques: bright color on dark backgrounds, gradients, parallel lines and sharp geometric figures sheer scale. The opening images in “Exquisite Logic” are nearly eight feet tall, and they’ve been hung high on the wall; unframed, they curl a little at the sides as they scroll toward the gallery floor. The bigger images are rendered on Japanese kozo paper, which imparts some of the airiness associated with Asian landscape art.

Some of these resemble obsessively decorated doors. Others are distinguished by a spine, running from the top to the bottom of the images. The verticality of these pieces suggests ascension; their texture and design keep them earthbound, tethered to artistic traditions. The pattern on “KB095-2” looks more than a little like those on a Navajo blanket. “CDS118164020” sports stark turquoise fields reminiscent of batik. “B53K4771” comes on like the cover of a sci-fi paperback - something by Phillip Dick, perhaps, about a portal into a digital world.

“DM624161212” by Pat Lay

The mandalas are smaller and quieter, but taken collectively, they’re no less immersive. These crisp, chilly squares feel like an encounter with an alien (perhaps artificial?) intelligence. It’s here where Pat Lay’s inspirations are clearest: The series of images called “Processor #1-6” are images taken straight from the bowels of a computer, balanced in the center of a grid and framed, a chessboard where Deep Blue always has home-field advantage. “DM610161212,” perhaps the most arresting of the mandalas, is a thick network of wires and chips straight from the circuit board. With the conduits in electric blue and the breakers in bright crimson, it could be a trippy still from a space opera: a view of a starship corridor seen through the infrared lenses of a Robocop.

Yet calling these images kaleidoscopic — evocative of sci-fi and the psychedelic symmetry of outer space flicks — doesn’t do them justice. The DMT daydreams of pieces like “DM423161212” are exciting, but they play a supplemental role; the callbacks to ancient Indian, Celtic, and Native American devotional art take the lead. It requires an artist of peculiar sensitivity to crack open a computer and find mandalas, crosses, and circles reminiscent of Himalayan sand paintings there. Lay may be on to something, even if it’s just our tendency to project our own technological aesthetic back on to artworks made by prior searchers for ultimate truth.

Although the tone is totally different, “Exquisite Logic” reminded me of the Zheng Guogu’s outstanding “Visionary Transformations” exhibition at MOMA PS1 last spring. Like Guogu, Lay is well aware of modern distortions that make apprehension of Buddhist art difficult. Like Guogu, she embraces those distortions and from them she spins some… well, we won’t say gold. Bitcoin would be more appropriate.

“Exquisite Logic” will be on view through March 12, and there’ll be a special event at the gallery for Jersey City Fridays. If you didn’t know that Dvora even existed, you’re not alone — until recently, I didn’t either. The space, which is raw but perfectly appropriate to an exhibition like this one, is right behind the big plate glass windows of an unused chamber on the first floor of the Oakman Condominium building (160 First St.). This is the premiere exhibition in the gallery, and it’s an impressive way to kick off. Presently, Dvora is programmed by the sharp-eyed people behind the Drawing Rooms gallery in the Marion neighborhood of Jersey City. When the Powerhouse Arts District was initially conceived, it was spaces like this one that arts advocates were imagining. We could use a few more like this one.

Pat Lay: Exquisite Logic

Dvora Gallery@the Oakman Condominiums

160 First Street

Showing until March 12

Special event for Jersey City Fridays

6-8 p.m., March 6

McCall, Tris; Tris McCall’s First JC Fridays of 2020 Roundup, Jersey City Times, March 26, 2020

Excerpt from Jersey City Times article:

In theory, JC Fridays means free arts events of all types. The organizers of the festival promise music and live performance and film and poetry. That’s no fib: All of that stuff is on the calendar at jcfridays.com, which you should check out immediately.

But in practice, JC Fridays is a visual arts celebration and a quarterly echo of the annual Artist Studio Tour that has defined the cultural life in this town for decades. There are more art openings and gallery events listed on the JC Fridays site than all other options put together. This means it’s a fine excuse to run all over Jersey City, taking in as much visual art as you can stand.

“Commit to Memory” is the cry of the natural world sliding toward desolation; “Exquisite Logic” teases out the humanity lurking in the belly of the machine. Pat Lay’s clever work begins with an image of a computer processor or electronic component. From there, she mirrors it, colors it and manipulates it until it achieves spiritual overtones reminiscent of Asian devotional art. Lay calls some of the images in her show “digital mandalas,” and that’s not a misleading description. They’re meditations on symbols and patterns with long histories — symbols and patterns that follow humanity around no matter how deep into the technological murk we go.

The Pat Lay show marks the maiden voyage of the Dvora Pop-Up Gallery at the Oakman Condominiums in the Powerhouse Arts District. When the District ordinance passed many years ago, it was spaces like Dvora that advocates were envisioning — accessible street-level galleries with works visible to passerbys. For the moment, the pop-up is getting booked by people who were around Jersey City during the Arts District fight: Jim Pustorino and Anne Trauben of the Drawing Rooms space in Marion. (Yes, that’s the same Anne Trauben I wrote about earlier; Jersey City rewards tirelessness.) They know their history and have a sense of what’s at stake. The interior of Dvora is a bit raw, and industrial, too, but that suits Pat Lay’s computer dreams extremely well. From the sidewalk through the plate glass windows of the Dvora space, the works look like persian rugs designed by artificial intelligence. That’s a compliment. (6-8 p.m., at Dvora, 160 First St., drawingrooms.org/dvora-gallery).

Yaniv, Etty; Pat Lay: Mapping New Interiors, Art Spiel Blog, March 18, 2019

artspiel.org

Etty Yaniv, March 18, 2019

Pat Lay, installation view in studio, photo courtesy of the artist

Pat Lay‘s Digital work conjures ancient iconography, or maps organized in what appears to be a binary logic. Throughout her abstracted digital and more figurative sculptural work she consistently reflects on the role of technology in our life, merging cultural cues with a seemingly mathematical order. For Art Spiel the artist elaborates on her interest in technology, what brought her to art, and her 42 year experience as an art educator at Montclair State University – both as a teacher and as the founding director of the MFA in Studio Art.

AS: You were born and raised in Connecticut and have been a professional artist since 1968. Tell me a bit about your art background.

Pat Lay: I come from a family of artists. My great-grandfather was an eminent New York portrait painter. My grandfather was a well-known landscape architect in New York and also a painter. Both of my parents have degrees in painting but after the war my father became an engineer and my mother a designer of solid-state circuitry, both working frequently for the space industry. My mother painted commissioned portraits in our living room in Connecticut when I was a young child. I was surrounded by artists as a child, visited art museums in NY on a regular basis, and took painting lessons starting at age 9. From a very young age I knew that I wanted to be an artist so I pursued art for my undergraduate studies at Pratt Institute and afterwards graduated from Rochester Institute of Technology with an MFA. At Pratt I met the artist Kaare Rafoss. We have been married since 1963.

Extensive travel has also informed and inspired my work. I traveled with my mother in 1962 to thirteen countries in Europe visiting almost every art museum and cathedral on the map. David Smith’s sculptures in Spoleto were a highlight of that trip for me. In 1968 I entered the art world as a sculptor working in clay. In 1975 my work was included in the Whitney Biennial. More recently, travels in Asia, Africa and South America have altered my view of what is meaningful, and visually powerful in art. Non Western Art is non formalist, ethnographic, more in touch with the intuitive and the human soul. The art works usually create a tension between the present cultural reality and the emotional and spiritual realm.

Pat Lay, 54AAA0254, 2015, collaged scroll, archival pigment printed on Japanese kozo paper, gold paint, Tyvek backing, 96 x 48 inches, photo courtesy of the artist

AS: You seem to focus on technological metaphors in diverse formats. What draws you there?

Pat Lay: I have always been interested in the juncture of math, science and art. The contrast between nature and manmade. Since 2000 I have been exploring hybrid forms to refelct a time of rapid technological changes –how the computer is central to our lives; how the body and mind are augmented and assisted by technology. As a result of this thinking I started dismantling computers. What I discovered inside was very exciting: colorful anodized aluminum cooling elements, wires, the beautifully designed hard drive, the minimal geometry of the processor, but most exciting was the motherboard or circuit board, a map of a new interior world.

In parallel, visiting museums has become an important and integral part of my practice. The African Art wing at the Metropolitan Museum has been my go-to place for inspiration for many years. My embellished head sculptures from 2001 to 2011 were influenced by Nkisi n’kondi/ Minkisi power figures of the Kongo peoples of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The DADA exhibition at MOMA in 2006, occurring when I was making both sculptures and two-dimensional works, made me question and helped me to better understand the paradoxical relationship between human consciousness and technology. Raoul Hausmann’s “The Spirit of our Time,” 1919, which was in the exhibit, piqued my interest in the use of readymade forms and mixed media.

Starting in 2000, my power figures combined and hybridized human elements and technology. This work incorporates fired clay, steel, mixed media and ready-made computer parts. The computer parts harbor intelligent data, imply a function, offer protection and emit power. Dada and Surrealism have been a profound influence on both the sculptures and the earlier collage works: Picabia’s “machines”; De Chirico’s metaphysical juxtaposition of objects (The Great Metaphysician, 1917; The Song of Love, 1914; The Disquieting Muses, 1917); Max Ernst’s early Surrealist works (Oedipus Rex, 1922; Women, Old Man, and Flower, 1923-24) and Magritte’s hybrid, metaphorical images.

Pat Lay, Life-Support #12, 2008, digital photo collage, Epson Enhanced Matte photo paper, Epson Archival ink, computer parts 17 1/2 H X 15 1/2 W X 1 1/2 D inches, photo courtesy of the artist

Pat Lay, Transhuman Personae #11, 2010, Detail, fired clay, graphite and aluminum powders, acrylic medium, computer parts, cable and wire, tripod, 75 X 46 X 46 inches, photo courtesy of the artist

AS: Your digital 2-D works conjure for me an array of visual and cultural associations – Persian tapestries, byzantine mosaics, illuminated manuscripts – underscored with an algorithmic logic. Is that on your mind and what’s your take on that?

Pat Lay: Yes, the work looks to art history for ideas and questions that are universal. Art comes from art. Historical works inspire new works. History gives me structures that I can work with.

In 2003 I started a new series of works on paper that were inspired by several exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The structure, patterning and border designs of the Persian carpets and Persian miniatures pointed the way to transforming patterns into digital structures. The circuitry of the motherboard became the digital media for creating new digital collages.

At the Rubin Museum in New York City I came to appreciate the power of Tibetan thangkas. I realized that I could work with paper in a much larger scale, up to 96 x 48 inches and turn a religious icon, the Tibetan thangka, into a contemporary abstract composition that serenely captures our world of technological advancement. At the same time the scroll format was a practical way to make large works easily portable.

Meditating on the past, present, and future, my scrolls question and critique our paradoxical relationship and obsession with technology and what it now means to be human.

Pat Lay, CADAC CMVO-2 #7, 2012, 22 x 18”, photo courtesy of the artist

AS: You are at home with both digital and sculptural forms. Let’s start with digital – what is your process?

Pat Lay: During 2014-2016 I was concentrating on a series of large collaged paper scrolls, 96 x 48 inches. Digital images scanned from computer circuit boards were printed on Japanese kozo paper and collaged into patterns that were transformed into a larger matrix: a logic with an aesthetic gestalt.

Pat Lay, KB095-3, 2014, collaged digital scroll, inkjet printed on Japanese kozo paper, gold paint, Tyvek backing, 96 x48 inches, photo courtesy of the artist

AS: And your sculpting process?

Pat Lay: With the current work, the “Soul Bots” series, I start with a computer part (I have been using aluminum heat sinks and heat sink cooler fans) and a solid ball of clay about the size of a melon. I shape the clay into a form that is either organic or a combination of organic and geometric. The computer part is crucial to the design of the clay form. When the clay is stiff I cut the form in half, hollow it out and then reform the two halves back together. After the work is completely dry I glaze it and then fire it to a mid-range temperature. After the firing the computer part is epoxied on to the clay form.

Pat Lay, SOUL BOT – X2C1, 2018, fired clay, glaze, mixed media, 5.5″ x 6″ x 5″, photo courtesy of the artist

AS: How do you see the relationship between your digital and sculptural work?

Pat Lay: All of my work deals with related issues. How do we as spiritual beings adjust to a culture and environment that is rapidly becoming more reliant on technology? How are we as humans changed by the new advances in technology?

Working both two-dimensionally and three-dimensionally gives me the opportunity to explore different kinds of space and various media.

AS: Your 2 latest series, “Soul Bot,” and “Z4E2” involve fired clay and seem to me as a shift in your work. What can you tell me about this new work?

Pat Lay: I am back working with clay after almost a five-year break from it. For most of my career clay has been my primary material. Starting in 1998 I became interested in two-dimensional works; then for a number of years, I went back and forth between two and three dimensions. By 2012 I was working exclusively in two-dimensions. But since 2017 I am back to working in clay. I love clay. I wish I could work in two-dimensions and three dimensions concurrently. But it doesn’t work for me. At some point I will go back to the collage works on paper but for now I am happy with the clay.

These are hybrid forms, robots, that question the human condition, the interface between man, nature and technology.

Pat Lay, SOUL BOT – Y3D3, 2018, fired clay, glaze, mixed media, 6″ x 6″ x 9.5″, photo courtesy of the artist

AS: You have had substantial educational roles. Can you share some of them and how they affected your art making?

Pat Lay: I taught at Montclair State University for 42 years. I was the founding director of the MFA in Studio Art. The program ran from 1999-2017. The courses that I have taught at Montclair State include figure drawing, sculpture in clay and MFA seminars that included visiting artists and discussions of the business of art. I also ran a visiting artists lecture series for undergraduates for about 35 years.

Having visiting artists come to Montclair State on a weekly basis kept me active in the larger art community and was a stimulation to explore new materials and concepts.

And the students, both graduate and undergraduate students were continuously expanding the definition of art, questioning its purpose and exploring new ideas. This kind of questioning and art activity is energizing and inspirational.

AS: What are you working on these days?

Pat Lay: At the moment I am continuing the “Soul Bots” series. When this series comes to an end I want to start a new series of collages that continues the use of digital data but also introduces forms from the natural world.

Pat Lay in her studio, photo courtesy of Alejandro Rubin

Naves, Mario; Half Human, Too Much Art

HALF HUMAN

By Mario Naves, Curator

Originally published on Too Much Art in 2018

Excerpt from Catalog Essay:

Few questions are as persistent — or frustrating — than those surrounding the meaning of what it is, exactly, to be human. Given the run of opinions and theories over the span of history, the human has proven a subject prone to perpetual re-definition.

Philosophers, politicians and religious leaders have attempted to interpret human nature and, in more than a few cases, codify it — sometimes for salutary purposes, sometimes not. If anything is constant about the “human”, it is inherent unpredictability, a slipperiness of need and ambition.

As we continue into the twenty-first century, how is the world we helped to shape shaping us? Every artist — at least, any artist worth her salt— works in response to the surrounding culture, if in ways that are closer to osmosis than reportage. Historical context doesn’t determine aesthetic worth, but it would be foolhardy to deny its influence. There is no escaping our self-awareness as a species. The artists featured in “Half Human” elaborate upon this predicament in ways that reaffirm its primacy.

The sculptures and assemblages of Pat Lay make a point of how technology is transforming the collective body and mind: her totemic visages combine the mechanical and the iconic, suggesting a dystopia that is less futuristic than we might like to admit.

Glover, Tehsuan; Aljira presents: Bending The Grid, The Newark Times, January 21

Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art is pleased to present Bending the Grid: Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams. This major survey exhibition highlights more than four decades of Pat Lay’s career. It presents, for the first time, a broad view of Lay’s expansive vocabulary in a range of various media and styles, influenced by her extensive travels and informed by her overlapping art and non-art interests. The exhibition demonstrates the breadth and prescience of Lay’s vision. It’s very expansiveness – including the combining of art and science – is a subject in itself, as is its tilt toward diverse forms, materials and content.

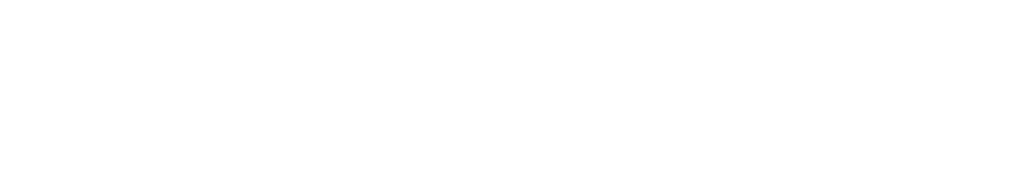

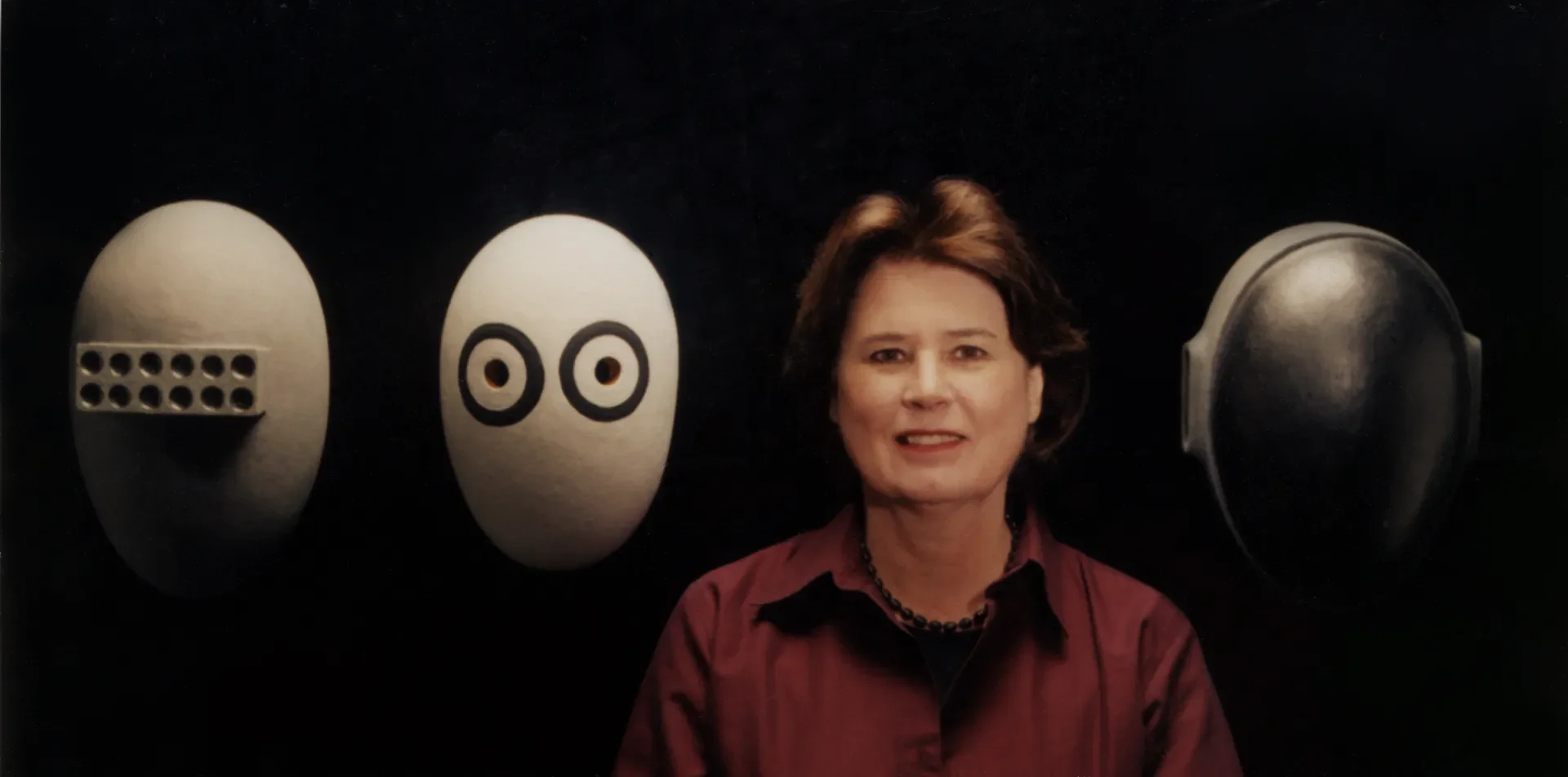

Pat Lay, photo credit: Robert H. Douglass

Tracing the trajectory of her development from 1969 to the present, with the emphasis on more recent work, Lay’s commitment to the experimental, the multidisciplinary and the hybridized is highlighted in this show, along with her interest in working with a wide range of materials. The earliest works are abstract, at times brightly colored, three-dimensional wall pieces made from glazed fired clay, when clay was still generally discounted as a craft medium in this country; it would become one of her signature mediums.

“From the beginning, it seems, Pat Lay has been fascinated by the unfamiliar, by cultures other than her own, especially from distant regions of the world. She was never dismissive of art that was free from European and American formulations, but was intrigued, instead, by its rich, often curious imagery and venerable histories, by its differences,” notes guest curator Lilly Wei. “Lay was also inspired by the many astonishingly talented, innovative women artists of the 1960s and 70s whose work broke new ground, addressing the same divide between the handiwork of what might be called ‘feminized’ pre-industrialized cultures and those of ‘masculine’ industrialized nations, between what was considered low and high art.”

In the past decade Pat Lay’s artwork has focused on technological metaphors of the human experience. Her sculptures, made of fired clay, computer parts and other ready-made elements, are hybrid, post human power figures that have cross-cultural references and question what it means to be human.

Pat Lay Transhuman Personae #11 (detail), 2010 Fired clay, graphite and aluminum powders, acrylic medium, computer parts, cable, wire, tripod 75 x 46 x 46 in.

Aljira’s commitment to Lay is two-fold: first, to make the full range of this artist’s oeuvre more widely known; second, to acknowledge the generous contribution she has made to educating and promoting the work of young artists as a founder of the Master of Fine Arts program at Montclair State University.

Saturday, March 12, 2016, 2–3:30pm:

In Conversation with Visiting Curator Dexter Wimberly:

During this talk, Pat Lay and Guest Curator Lilly Wei will discuss the cultural influences that inform Lay’s work as well as Lay’s commitment to the experimental, multidisciplinary, hybridized works featured in Myth, Memory and Android Dreams.

Bending the Grid: Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams is documented by an illustrated catalog, including an essay by the guest curator Lilly Wei and an interview with independent art curator, writer and chairman of the board of Independent Curators International, Patterson Sims. Three limited edition prints by Lay, donated by the artist to benefit Aljira’s exhibitions and programs, will be available for purchase for a limited time during the exhibition. On sale at shopAljira beginning January 21. The exhibition will be on view at Aljira through March 19, 2016.

A graduate of Pratt Institute and Rochester Institute of Technology, Lay is a retired Professor of Art at Montclair State University. Lay has received two grants in sculpture from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and a grant from the American Scandinavian Foundation. She has been awarded three public art commissions including the installation of a large-scale site-specific sculpture in the sculpture park at the Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter in Oslo, Norway. She has had solo exhibitions at the Jersey City Museum; New Jersey State Museum; and Douglass College, Rutgers University. Her work has been included in group exhibitions in Japan, Austria, Korea, China, Norway, Wales and Slovakia and at the Jersey City Museum, Newark Museum, New Jersey State Museum, The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Montclair Art Museum, The Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Everson Museum, and the 1975 Biennial Exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Lay’s work is featured in a number of books including Lives and Works, Talks With Women Artists, Volume II by J. Arbeiter, B. Smith and Swenson.

Zimmer, William; ART REVIEW; Brimming With Color and Light, The New York Times, January 27, 2016

THE long-term mission of the Jersey City Museum is to show contemporary art that is outside the mainstream, usually by artists who have not had much exposure. That mandate is reflected in the Winter 2002 Fine Arts Annual, the second show in the museum's new building.

Seven museums around the state take turns as host of this annual exhibition, which is sponsored by the New Jersey State Council on the Arts. This year, the curators were Rocío Aranda-Alvarado, from the Jersey City Museum, and Victor Davson, director of Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art, in Newark. In choosing the works, they had an eye for color and light, and took advantage of the ample light coming in through the museum's large windows and skylights.

The mylar ''Bouquet'' by Henry Sánchez from Jersey City is suspended in the lobby. In this work, Mr. Sanchez revives the old art of the silhouette; the edges of the mylar flowers are each cut with a profile of one of his friends or family members. It is a subtle effect, and viewers might have to have it pointed out to them, but it turns the work into a tribute.

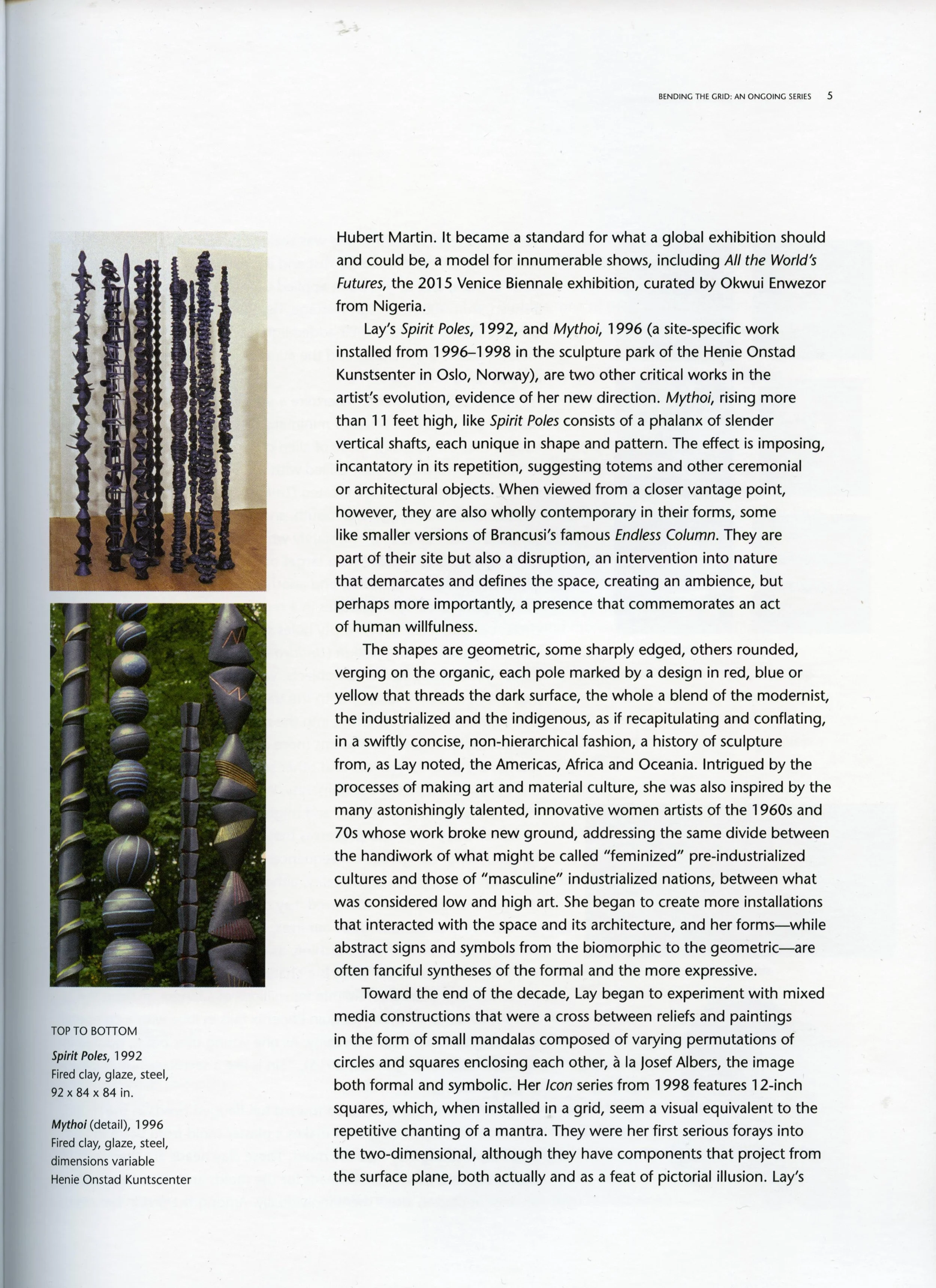

At some distance from ''Bouquet'' is an untitled ceramic head by Patricia Lay, also of Jersey City. The piece is painted silver to catch the light. But the silver also makes the work look robot-like and does not lessen the unease that a viewer may feel because the head is mounted on a stand at eye level with the average person. Its intense gaze leads to the conclusion that it reads thoughts.

The small first-floor gallery has been painted dark gray to enhance the chromatic quality of several of the pieces displayed.

''Panorama'' by Arturo Arbuzo D'Anhilli Virtmanis from Jersey City is an urban vista. Painted bright yellow, it has a pattern of short black diagonals reminiscent of traffic caution signs. ''Rainbow Vamps,'' two photographs by Betty Guernsey from Irvington, are images of rows of mannequin heads wearing wigs. The wigs' colors make a rainbow. Young Cheol Yoon from Jersey City used a paper shredder to create strands of various paper, some metallic, which are mounted on wood to yield works with densely woven surfaces.

Upstairs is ''Femur and Fragment'' by Matt Schwede from Hoboken. This work consists of bones made of wood and plaster, and covered with aluminum leaf. They are larger than life unless the life in question belongs to a dinosaur.

''Found Object, Jersey City, New Jersey'' by Shandor Lafcadio Hassan of Jersey City was inspired by a journey he made from California to New Jersey, picking up items he thought were quintessentially American and making them into art to hang on a wall. In this show, he displays a portion of the rusted front of a Ford, which he found in New Jersey, and whose headlights he re-lit. It works as a gesture of homage, perhaps to America or to Jersey City.

Many pieces like this impress because they are in the spirit of paying tribute to someone or something. Others are notable because they were labor-intensive. For instance, the complex patterns meticulously drawn with ink and metallic marker by Sharon Libes from West New York might astound the viewer by their example of hard work and concentration producing beauty.

Also beautiful, in the light- and color-filled way that distinguishes much of the show, are ''Argirio's Portal'' and ''Meditation with Yellow Distraction,'' two paintings by Giovanna Cechetti from Paterson. These have patterns somewhat more errant than Ms. Libes's that may remind viewers of works by Gustav Klimt.

The show is low on art containing written language though some pieces incorporate cartoon or other appropriated images. ''Profiles -- Blue'' and ''Magic Tricks'' by Bill Leech from Roosevelt are impressive in this vein, the latter because the image of a top hat seems to fade away on the surface.

''Space Girl'' by Jon D. Rappleye from Jersey City, is a small warm-up for his panoramic ''Plucked from the Vine, Ripe for the Harvest,'' in which various, seemingly mutant characters weave in and out of a lattice pattern.

The most coherent narrative painting, one done in a realistic style, is ''Veneration'' by María Mijares from Plainfield. The small canvas depicts a group of priests prostrate at a church. The viewer does not see the object of their worship, but gets involved comparing the various soles of their shoes.

A couple of assemblage pieces that might be regarded as paintings stand out. For example, German Pitre from Newark recalls his childhood in ''(Untitled) Fear of the Dark.'' This work has stuffed animals painted black mounted on a wooden rectangle also painted black. The artist's message is hard to miss.

Helen M. Stummer from Metuchen, who seems to be an intrepid documentary photographer, has ''July Heat'' and ''Rayshawn -- Easter,'' two black-and-white pictures, in the show. These works focus on African-American children. Megan Maloy from Hoboken documents her self in various guises. She is behind the wheel in ''Demolition Derby 2'' and a beer guzzler in ''Self Portrait in Doug's Trailer 1.''

The ''Winter 2002 Fine Arts Annual'' remains at the Jersey City Museum, 350 Montgomery Street, Jersey City, (201) 413.0303, through April 28.

Lawler, Anthony K.; Lay with Machines, Not What It Is Blog, February 25, 2016

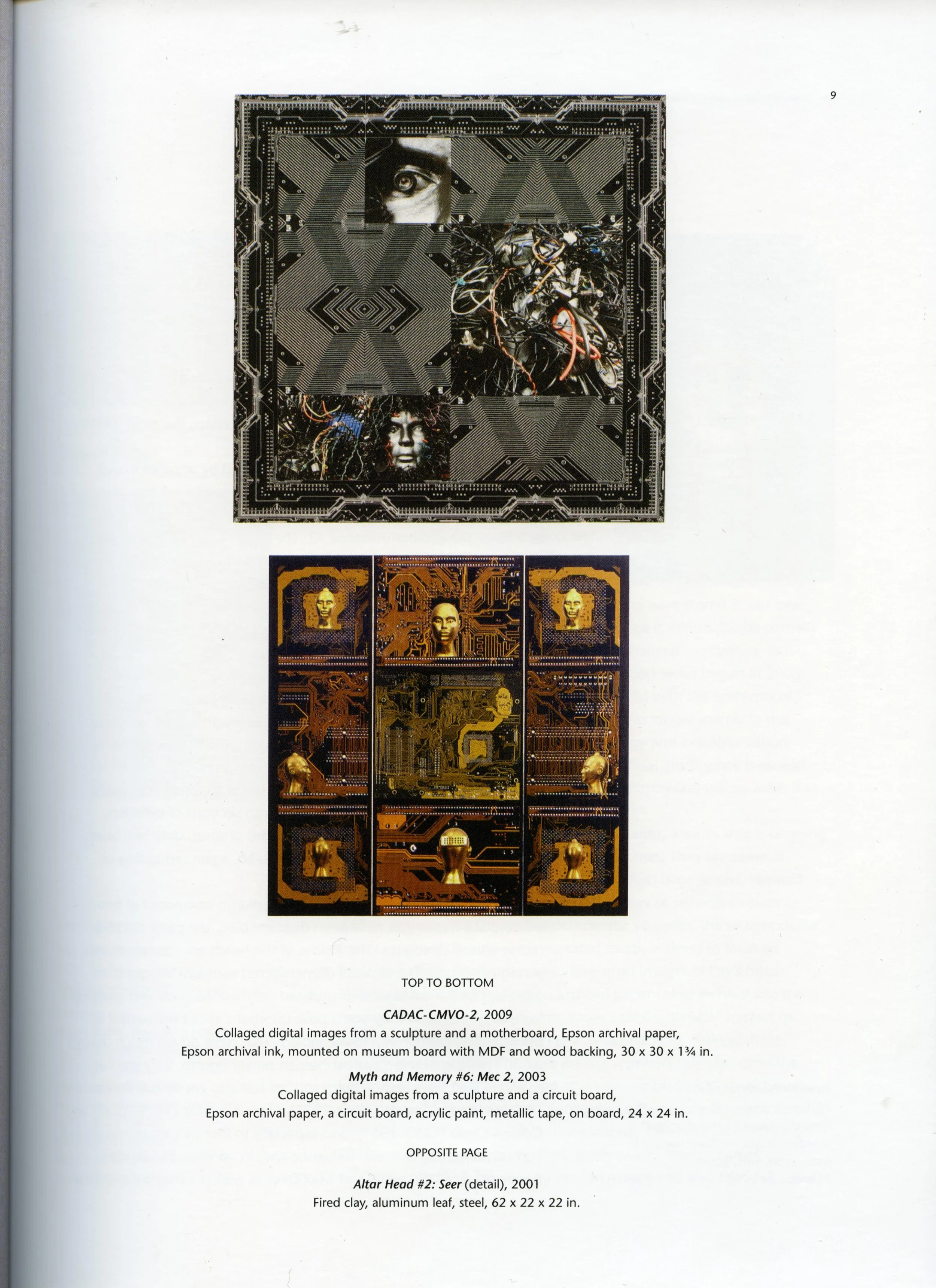

Image: CADAC-CMVO – 2, Pat Lay

A wonderful expanse of creative vision and technological empowerment – a reflection of the rise of our digital age – is currently on display at Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art in Newark, NJ. The artist, Pat Lay, explores in her work a variety of materials, construction methods and thought processes. Aljira’s gallery exhibit is currently displaying work by Lay from the advent of her career in the late 1960’s through and up to the present moment.

Using the patterned line work found in computer circuitry, Lay’s 2 dimensional pieces evoke a mysterious, spiritual and cosmological attachment to technology. The viewer is staggered in their position as each new piece comes into view through the details and meticulous weaving of line and pattern. Several of the pieces are balanced along an axis of symmetry, with one or two elements suspended in a dimension above. Whether digital figures or a view of the cosmos, the juxtaposition of these two entities deliver the work in an interesting and compelling way.

Image: CBA-E-VO-A #2, Pat Lay

Image: SFL40VO #17, Pat Lay

The work jars the schemas of memory by presenting us with familiar icons, such as that of the tapestry, only to realize the details are not of hand stitching, love and thread but instead of wire, electricity and metal. Our human attachment to each piece is thrown into an artificial realm, ushering us toward a new visage of the future.

Each piece is a hybridization of that which expresses our humanity and that which represents the children of our civilization, the machines.

Successors

Lay’s work alienates us, yet draws us in. We are familiar with the forms and elements, yet the non-humanism squirms under our skin. Her android creations are a vision of Transhumanism; they are the product and inevitable conclusion of our tech-society. The emergence of Lay’s machines rises from us, the organics, but settles into an unclear context of whether these geometrics they will express the current values of humanity, or reject them.

Images: Transhuman Personae #6 (left)

Transhuman Personae #1 (right), Pat Lay

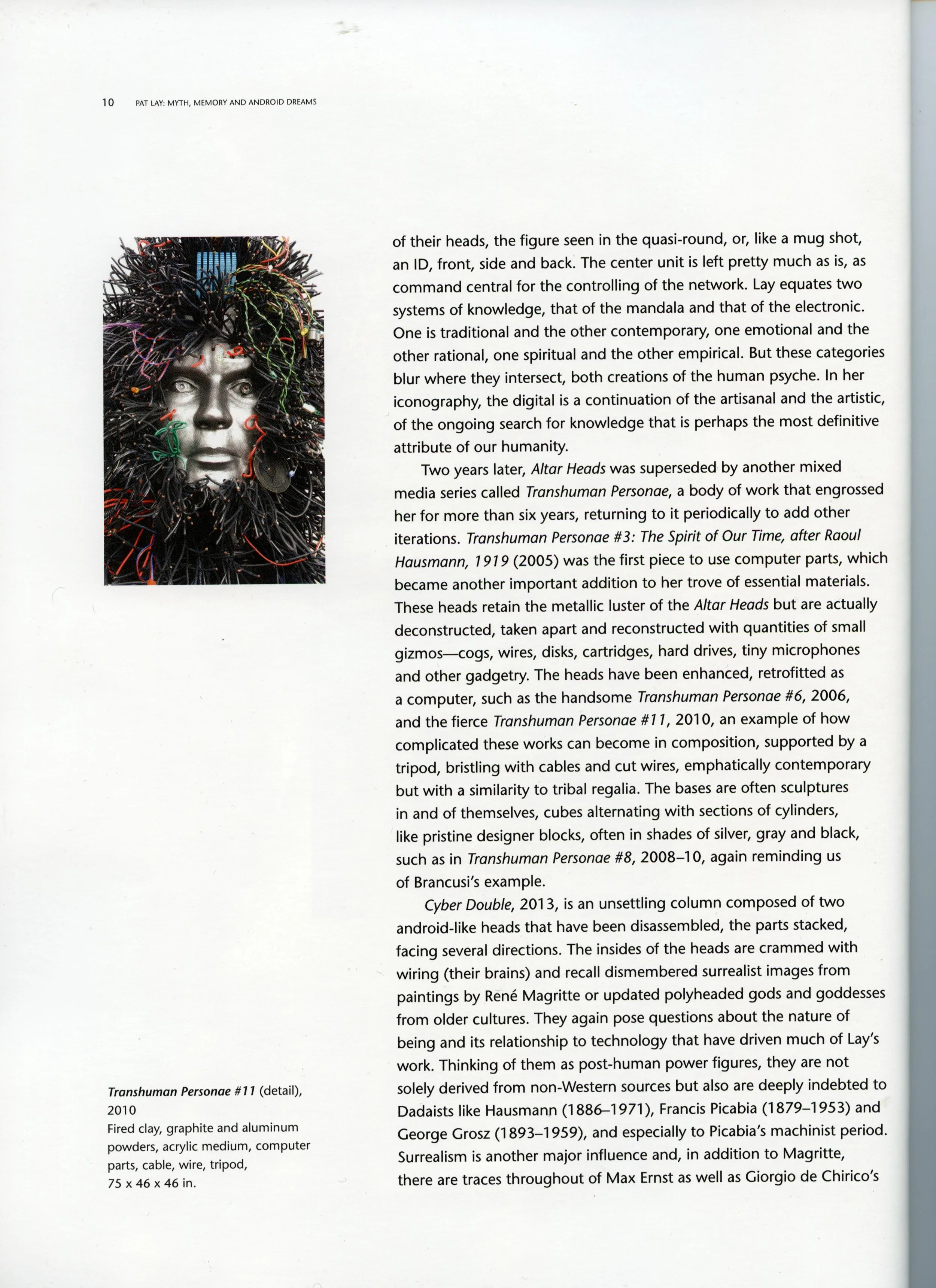

Image: Myth and Memory #6: Mec 2, Pat Lay

The 3 dimensional figures on display balance an interesting harmony between Lay’s early and latter work. This retrospective layout, provides the viewer with a narrative of forms, ones which rise from minimalism and drift into full complexity. Lay’s practice grew during the time of minimalism and the rejection of clay and ceramics as a fine art material. Lay’s ceramic forms function as quiet, yet expressive totems of design and empowerment. The balance between geometric shapes and organic material present themselves with mastery over their forms and the expression of the culture they represent.

Aljira’s guest curator Lilly Wei stated, “From the beginning, it seems, Pat Lay has been fascinated by the unfamiliar, by cultures other than her own, especially from distant regions of the world. She was never dismissive of art that was free from European and American formulations, but was intrigued, instead, by its rich, often curious imagery and venerable histories, by its differences.” I would further add that the narrative in Lay’s work, regardless of medium or context, continues to express her interests in experimentation and the evolution of humankind through form and material.

Image: Spirit Poles, Pat Lay

Image: Untitled, Pat Lay

Image: Mask #1, #6, #5 & #8, Pat Lay

Lay is a graduate of Pratt Institute and Rochester Institute of Technology. She is the founder of the Master of Fine Arts program at Montclair State University, through which her influence and support has bolstered the quality of art in New Jersey nearly as far into the future as her own post-human creations.

The series Myth, Memory and Android Dreams by Pat Lay will be on display at Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art until March 19, 2016. Aljira is located at 591 Broad St, Newark, NJ 07102. For further information on Pay Lay, visit her website at – you guessed it – www.patlay.com or visit Alijra gallery at www.aljira.org

Skorynkiewicz, Kasia; Review: Pat Lay at Aljira, Not What It Is Blog, March 11, 2016

Artist Talk this Saturday, March 12, 2016, 2-3:30pm

Join Pat Lay and Guest Curator Lilly Wei In Conversation with Aljira Visiting Curator Dexter Wimberly

As I walked into Aljira art gallery in Newark, NJ to see Pat Lay’s newest exhibition, I was immediately greeted by a creature standing about the height of a human but made of tripod legs, an abundance of electrical wires, and other computer parts. The only human element was a silver face emerging out of the forest of black cords. Though there was something foreign about this piece it also felt very much familiar at the same time. And that’s when I realized that I just stepped into Pat Lay’s world.'

Perhaps this wasn’t one of Lay’s most important pieces in the collection but it was an indication of what was to come. The gallery was intermingled with wall pieces that were made up of brightly colored symmetrical patterns, which conveyed a sense of playfulness, but the systematic pattern transmitted a rigid and controlled feel. Mixed within these technological components were human elements in the form of silver heads fired from clay that were also composed of more computer parts. And even further into the gallery, the clay component becomes more prominent with many sculptures being made from clay. Though those sculptures seem to concentrate on formal questions, they also seem like they could be creatures that exist in this futuristic hybrid world that Lay is investigating.

I gravitate from on piece to another as if I were a pinball inside a machine, bouncing from one piece to another. Though at first, the pieces seem entirely different, they actually link two worlds together, the past and the present. Lay intertwines the old and the new in a refreshing way. The old is underlined by the use of clay, which still struggles between high and low art. Lay pushes the boundaries of where the human experience ends and where technology begins. Perhaps this hybrid world is our future, where we are interconnected as both human and machine. As a whole, I thoroughly enjoyed Lay’s vivid and hybrid portrayal on the human experience. Whether it is the future world, it’s still a place that remembers it’s past but embraces the future. Pat Lay’s world bends the grid with this exhibition bringing the past, the present, and the future into one interwoven experience.

Spotlight on Pat Lay: Bending the Grid: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams, Aljira Blog, March 8, 2016

Bending the Grid: Pat Lay: Myth, Memory and Android Dreams is a major survey exhibition that presents for the first time a broadened view of Lay’s expansive life and work – in two and three dimensions – in a range of media and styles, influenced by her travels and informed by her overlapping art and non-art interests. In Thailand, Cambodia and India, Lay was struck by the impact and spiritual beauty of Buddha and Hindu deities and in the power emanating from the idealized human form.

Photo Credit: Robert H. Douglas

“By the 1960s and 70s, Americans could no longer maintain a blinkered, isolationist stance regarding the non-Western world. Nor did most want to. How do you keep them down on the farm once they have seen Paree (and beyond) was a question from a popular World War I song. The answer is: you can’t. Our intertwined world continues to grow ever smaller, connected by air, land, sea, and instantaneously, miraculously, by intangible global networks of all kinds – for better or worse,” notes Guest Curator Lilly Wei in the exhibition’s fully illustrated catalog. “Lay, intrigued, speculates on the impact of artificial intelligence in the future, from computers to cyborgs to the yet to be imagined,” writes Wei.

Lilly Wei is a New York-based independent curator and critic whose focus is contemporary art. She has written regularly for Art in America since 1984 and is a contributing writer and editor for various national and international publications, including ARTnews, Sculpture Magazine and Art and Auction, among others. She is the author of numerous exhibition catalogs and brochures, and has curated exhibitions in the United States, Europe and Asia. Wei lectures on critical and curatorial practices and serves on advisory committees, review panels and the boards of several art institutions and organizations.

On March 12, 2016 Pat Lay and Lilly Wei will be joined by Visiting Curator Dexter Wimberly in conversation at Aljira. A fully illustrated catalog with an essay by Lilly Wei and interview with Patterson Sims is available to purchase. Here Pat Lay shares more about the exhibition and her process.

Pat Lay, Lilly Wei and Dexter Wimberly at opening reception (Photo Credit: Akintola Hanif)

ALJIRA: How does it feel to see and present your work spanning so many years in this major survey?

LAY: I’ve never seen it all in one place. Some of the work was stored in my basement and I hadn’t seen it in 30 years. I was hoping everything was still in tact. Seeing the work after 30 years was one thing and seeing it all together was a wow moment.